When screech-owls cry

and ban-dogs howl

People looking for a chilling Shakespeare quote usually go to Macbeth. Right at the start, one of the witches, seeing the approach of the laird, croaks ominously,

By the pricking of my thumbs

Something wicked this way comes.

Yes, indeed, considering the antics Macbeth was soon to commence. The inversion of the syntax shrouds the words in dark, ugly prophecy. (“Something wicked is coming this way” doesn’t work nearly as well.) Ray Bradbury liked it so much he built a novel around the image the phrase conjures.

Even so, however, for our money, it’s hard to beat Bolingbroke in Henry VI, Part 2 as he prepares to summon a prophet-spewing apparition:

Wizards know their time:

Deep night, dark night, the silence of the night . . . The time when screech-owls cry and ban-dogs howl, And spirits walk and ghosts break up their graves

Bolingbroke wasn’t kidding around. Anyone who encountered a ban-dog at night would have agreed. They were kept chained during the day to make them all the more eager for flash-ripping work in the dark. Otherwise, walk by a cemetery while mentioning ghosts breaking up their graves and watch your companion’s pace instantly improve.

This sort of imagery is most effective when it finds subjects willing to suspend their critical faculties, which is why it’s always sobering to stumble across someone who has not only retained his critical faculties, but has employed them, rigorously, and still sees ghosts.

For the fact is, some people with respected reputations who lived closer to our time than did Shakespeare’s characters have been deadly serious about dead people meandering among us as ghosts. Less than a hundred years ago, the reminiscences of a fellow named E. A. Reeves ended with an entire chapter devoted to his frequent encounters with the supernatural and his experiences at séances. He described these events as entirely credible and insisted that the apparitions of dead friends were legitimate because they knew things that only they could know.

Reeves was a man of the modern age, but he also lived in a world of strange noises and peculiar events. He saw Lord Kitchener on the wall of his bedroom. On what must have been among his most memorable brushes with the supernatural, he watched what he took to be a living, breathing man vanish through a solid tile wall at the Knightsbridge tube station. Reeves’s life imitating Rowling’s art.

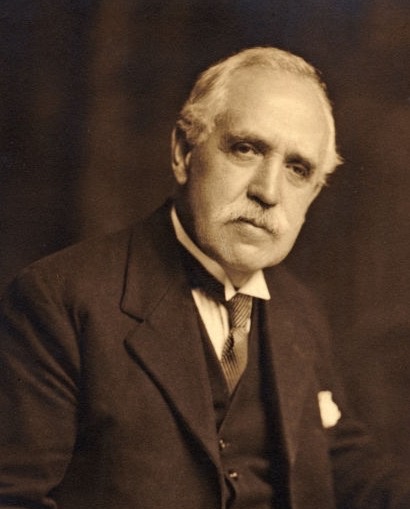

Well, he was a kook, you might say. But hang on. Edward Ayearst Reeves is a forgotten figure today, but people of his time took him for a sober man with a sterling character. For many years he served as the chief Map Curator and Instructor in Surveying for the Royal Geographic Society, a group indispensable for showing the pre-World War I generation of Englishmen how to survey land and accurately map it. Over his long career, he received coveted prizes and awards, including the Victoria Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society.

His memoir that included all the bizarre stuff crammed into that final chapter was prosaically titled The Recollections of a Geographer. As you’d expect, it mostly charted a career concerned more with plumb bobs than poltergeists, because Reeves was hardly a credulous naif. Instead, he was a serious man trained to make precise observations, commit them to paper in meticulous detail, and teach others to do the same. Yet he said he saw dead field marshals in his bedchamber and people walking through walls at train stations.

Edward Ayearst Reeves, was born in 1862 and died in 1945, making him a man of the modern era. He was a celebrated scientist and card-carrying sobersides. He also saw ghosts.

E. A. Reeves reminds us that those who believe the supernatural transcends superstition are not always nuts. Understanding that attitude is key to understanding the “ghost story.” Often it is merely an entertainment for those temporarily willing to suspend their disbelief, such as patrons of scary movies or readers of Stephen King novels. Those people don’t believe in ghosts, but they enjoy what Alfred Hitchcock seized upon as the universal relishing of fear felt in safety. People like E. A. Reeves are different. They do not temporarily suspend disbelief. Instead, and for some reason, they embrace the improbable as plausible and real.

Others do this for other reasons. For some, ghosts can also comfort the bereft. Mary Lincoln coped with losing her children by consulting seers and holding séances in the White House during the Civil War. She even persuaded her husband to attend one or two of them. He humored her, an example of how a combination of grief and the indulgence of loved ones could account for spiritualism’s popularity from the late nineteenth into the early twentieth. But the predatory motives of seers could be despicable. They took advantage of wounded people to separate them from their money.

It’s easy to see then how unbending realists would have none of it. They branded mediums as hucksters and their events as hoaxes. The magician Erik Weisz who performed under the name Harry Houdini spent much of his career trying to convince the public that séances were nothing more than ghoulish stunts. For doubters, the mantle of science, as in the case of Reeves, was not a compelling endorsement of the supernatural. Neither was the integrity of the clergy, as the case of Caleb Colton shows.

Colton’s brushes with the supernatural occurred about a century earlier than those of Reeves. Colton was a fellow of King’s College, Cambridge, and had assumed the curacy of Tiverton in Prior’s Quarter, Devonshire, when he heard of strange goings-on at a house in Sampford Peverell about five miles away. Rumor told of a haunting, and Colton’s visit to the house in the summer of 1810 convinced him that events there were “extremely troublesome.” Loud noises and a hammering on walls and floors commenced at random times during the day. Whatever was making the noise seemed to follow people around the house. It moved through all barriers, even ceilings, while banging away with such violence that teacups rattled, and the whole place shivered. At night, things got worse, as they always do in these stories. Random shrieks replaced the pounding. Their source was undiscoverable.

The sounds were unnerving enough. The sight of bed curtains being rapidly pushed opened and closed by invisible hands was beyond disconcerting. But worst of all, and most unusual for a poltergeist, there was physical violence. Maidservants were beaten in their beds by arms without bodies but strong enough to leave welts and bruises. A candlestick once flew across the room and nearly beaned the head of the household. Now here was the ghost story as it is meant to be told. There was none of Reeves’s pleasant chats with old (dead) friends or visits from avuncular military men. This was a haunted house that was terrifying its inhabitants.

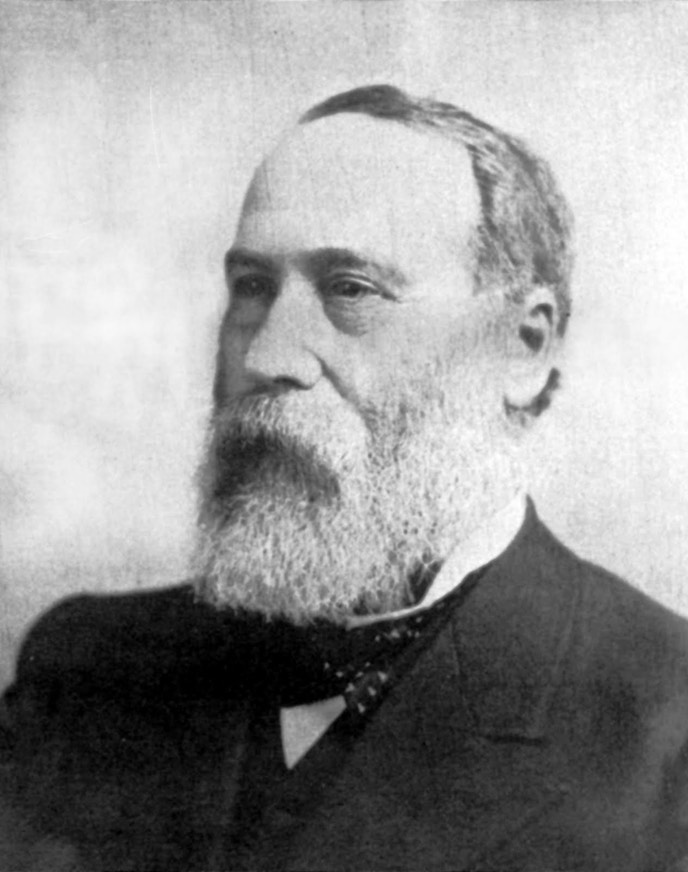

Charles Caleb Colton

Or so the Rev. Colton believed. Though he never saw any of these occurrences, he was mightily impressed by those who said they had. He chronicled their testimony in a letter to the local newspaper. When the editor declared the whole affair a hoax, implying that the visiting clergyman was a gullible ass, Colton took offense and did more than stick to his story. He started a pamphlet war with the skeptical editor. It made the “Sampford Ghost” a national sensation when newspapers throughout England began recounting the story.

Yet the Sampford Ghost was most certainly not a poltergeist, the German for “noisy ghost.” It was, in fact, a relatively transparent fraud. The servants had not even taken the trouble to hide the indentations caused by the mop handles they were using to bang around the place. The man who was renting the house was having a dispute with its owner, and nothing says lease-breaker like an alarming supernatural event.

Colton’s motives in telling the story are also murky. His pamphlet made him a minor celebrity, which he capitalized on with a unique talent for coining memorable sayings. He is supposed to have originated the aphorism, “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery,” and if the claim is valid, it’s apt. He plagiarized much of the account of Sampford from another ghost story that had caused a sensation fifty years earlier.

At the time, his seeming readiness to believe anything told him made him “conspicuous for anything but wisdom,” but there is a good chance that he knew the truth about Sampford and chose not to let it get in the way of a better story. By the time Colton killed himself in 1832, he had ceased being a churchman and had developed a destructive addiction to gambling. Possibly his suicide was caused by anxiety over impending surgery, but his obituaries resurrected the ghost of Sampford as one of his most defining moments.

Whether a real spirit or not, the force of the old demon Caleb Colton said he had found in Devonshire seems at the end to have caught up with him. In that, Reeves, Colton, and the noisy events at Sampford Peverell remind us of an unchanging feature of the human story: what is true doesn’t matter as much as what people want to believe.

Happy Halloween!