On February 22, 1794, George Washington received one of the best birthday presents he could have wished for. It wasn’t wrapped, it had no bows, and it did not even come as a surprise. Rather it was a person. Secretary of State Edmund Randolph was scheduled to introduce Jean Antoine Joseph Fauchet to him.

Fauchet was the new French minister, and it wasn’t so much him or his personality that endeared him to the president. It was the fact that Fauchet was not Edmond Charles Genet, the man Fauchet was replacing. Everything about Fauchet’s behavior indicated caution, prudence, and punctilio. After arriving in Philadelphia, he immediately called on Secretary of State Randolph to present unsealed copies of his instructions. That deed alone set Fauchet favorably apart from Genet. Randolph conducted the ceremony briskly on February 22, mindful that it was Washington’s birthday and the president would be busy. It went almost perfectly, in fact. The only flaw was that Fauchet wanted the American government to turn over Genet. Washington was sorely tempted.

Genet had landed at Charleston, South Carolina, the previous April to a rousing welcome. The place of his debarkation signaled the onset of trouble from the start. The United States capital was Philadelphia, and accredited diplomats were obliged to present credentials to their host government immediately after arriving in country. Genet knew better, but he didn’t care.

Citizen Genet

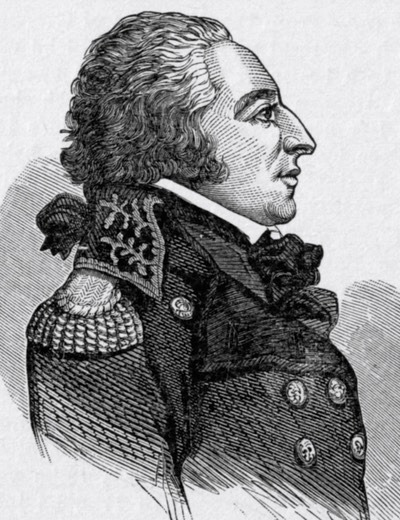

It was most strange, because Genet was neither stupid nor unlikeable. He was young (only thirty) but experienced, intellectually gifted, and a natural polyglot with a boyish charm that made every man his friend and every woman his mother. As chargé d'affaires to the French embassy in Russia, Genet had that effect on Catherine the Great. At least, he had that effect until he began spouting off about the pending revolution in France. Though styling herself a creature of the Enlightenment, Empress Catherine was an autocrat at heart, and she had Genet sent home under a cloud. It might have been the end of his career had not the French Revolution resurrected it.

The people who sent Genet to America were not blind to his flaws, and they warned him about brash conduct. By the time he began his journey, France was at war with most of Europe, and Genet was supposed to seek American help with subtle reminders of the 1778 Franco-American treaty that had helped the United States win its independence. He would try to achieve these goals in ways stunningly wrongheaded, though, beginning with a ten-day stay in Charleston where he commissioned privateers to prey on the British merchant fleet. Genet's defenders would later point out that the Washington administration had not yet announced American neutrality in response to the European war. The problem was that when Genet did know about American policy, it did not make any difference.

He traveled overland to Philadelphia, rallying crowds and meeting important people along the way. It took him twenty-three days to travel to Philadelphia where he finally presented his credentials. By then, the cheering throngs had convinced Genet he could do no wrong. In reality, he had all but undone his embassy before it was officially established. Before George Washington ever laid eyes on “Citizen” Edmond Charles Genet, he mildly despised him.

It only got worse. Genet’s privateers began bringing British prize ships into Philadelphia. It not only seemed to explode American neutrality but also threatened to throw the United States into war with Great Britain. Under pressure, Genet promised then Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson that he would not commission additional vessels to attack British shipping. But he soon proceeded to outfit a privateer right there in Philadelphia. Challenged about the matter, Genet reportedly said he would circumvent the doddering Washington’s silly neutrality by appealing directly to the American people.

That was the final straw for Jefferson. At first he had admired Genet’s enthusiasm, but the young man’s chronically inappropriate behavior was doing irreparable damage to Franco-American relations. One of the final bits of business for Jefferson before retiring from the State Department was drafting the request for Genet’s recall by Paris, a move heartily endorsed by President Washington.

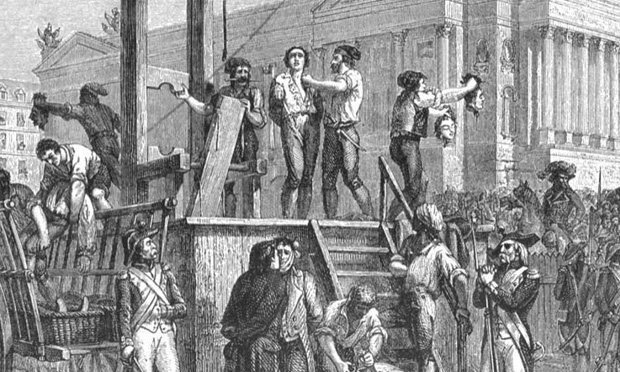

Since it is a formal way to kick somebody out of a country, a request for recall remains one of the most devastating blows that can befall a diplomat. But in Genet’s case, the disaster was compounded by his falling out of favor with his own government. The French Revolution’s increasing radicalism brought about a government that was convinced Genet wasn’t inept but was a counterrevolutionary deliberately alienating the only friend France had. The French sent grim emissaries with Fauchet to take Genet into custody and return him to France. The Reign of Terror was in full flower, and nobody doubted Genet’s fate once he was back in Paris.

The Reign of Terror

Washington must have been sorely tempted. Yet when Fauchet requested Genet's arrest, Jefferson’s successor at the State Department stalled. Edmund Randolph did not like Genet any more than Washington did, but neither man would send him home to die. That decision had already been made when Fauchet entered the president’s residence to present his credentials. Washington’s calendar was filled with official visits for his birthday. Cake and punch were served throughout the day, and a “splendid ball” that evening capped the observances. Fauchet was included in all the celebrations, but he looked glum.

He eventually had the good sense to drop the Genet matter as counterproductive to his primary goal, which was to restore good relations with the United States. It was like George Washington to match a gift by giving another, in this case safe refuge for a man who had thought him doddering, his policies wrongheaded, his popularity malleable. It had all made President Washington visibly angry, but it had not made him vengeful. Jefferson had known it would be like this, as did Randolph. Even Alexander Hamilton, who would have gladly sent Genet to his fate, knew that his chief would not.

They knew George Washington, who knew something about the sleep of the just.