Shortly before 10:00 on the night of April 18, 1775, sergeants entered the barracks of the British soldiers quartered in Boston and began putting together a force to march on the Massachusetts interior. The sergeants spoke in whispers to the men they gently shook awake and managed to spirit them out the rear of the barracks so noiselessly that no one else stirred. Even sentries at their posts didn’t notice. Already outfitted and now assembled, the men did not know their destination but only that they should be silent as they moved through the streets. When a stray dog spotted them and barked, a grenadier soundlessly broke ranks and killed him with a bayonet. And so the 700 soldiers reached the beach near a newly built powder magazine and boarded boats that glided out on Back Bay with oars covered in fabric that made them heavy but silent. The element of surprise was crucial to their mission. Their officers were pleased by the discipline that had preserved it.

Nobody had noticed the two pinpoints of light that had shown for just an instant from the steeple of Christ Church. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem about Paul Revere’s ride has the reason for the lanterns in the church’s belfry backwards: they were not a signal to Revere about a British route by water rather than land. They were an alert arranged by Revere himself to the Sons of Liberty to announce that British soldiers were beginning an operation that Americans had known about for days.

The supposed secrecy of the British would have resembled farce if killing had not been involved later on. General Thomas Gage had become a man vexed and bewildered by a crisis that would not pass and tempers that would not cool. Boston was angry, and the country to the west had become a setting for drum-beating militia and a communication system that could use bonfires and musket reports to muster men in minutes. A Committee of Correspondence was ominously in touch with the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, and a body styling itself the Massachusetts Provincial Congress was acting like a government to rival the king’s. It was embarrassing and exasperating for Gage, who was the king’s representative first as the Bay Colony’s governor and then as events spun out of control, as a general in charge of a military constabulary charged with keeping the peace. As tensions mounted, the hard faces of Bostonians made the soldiers feel like an occupation force. The soldiers sometimes acted like one.

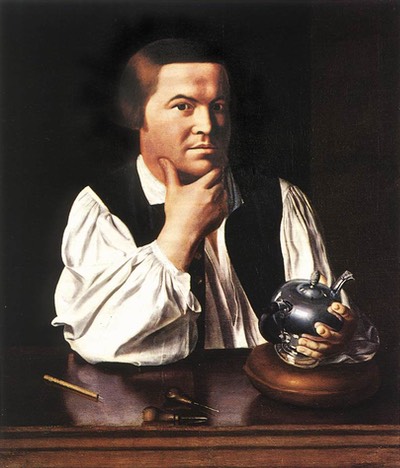

A family man with a prosperous silversmithing business, Paul Revere was an unlikely revolutionary, but they all were.

In Boston, Dr. Joseph Warren had become a central point of contact for colonial discontent, and he had summoned Revere to his house at almost the same time the British soldiers were leaving their barracks. From his intelligence network, Warren suspected the British were either heading for Lexington up the Charles River to arrest John Hancock and Samuel Adams or farther on to Concord to confiscate munitions and cannon. Warren had already sent William Dawes overland to Lexington, but to be sure someone got through he wanted Revere to take a short though more perilous route to Lexington as well. It was upon leaving Warren’s home that Revere arranged to have the lanterns flashed from Christ Church, and then he had friends row him across the river to Charlestown. The moon was rising and a flood tide was swinging the HMS Somerset at anchor, giving sentinels an excellent chance to see Revere’s boat, but it kept in the shadows of the shore and safely delivered him. He was given a fast horse but also a disconcerting warning. The road to Lexington was already being patrolled by British officers.

That was bad news. Revere knew that he was well ahead of the lumbering and large body of soldiers still in their boats behind him, but prowling patrols in his front would have made a less determined man pause. Instead, Revere swung himself into the saddle and spurred the horse to a gallop. It was an hour before midnight.

Revere’s ride to Lexington was a dangerous adventure, as his capture while on the way to Concord proved.

Only a few minutes passed before he ran up on two mounted British officers who wheeled to cut him off and then gave chase. Revere wheeled as well and escaped when one of his pursuers bogged down in a clay pond. Revere then altered his route with a prudent detour to Medford where he rousted a militia captain before pounding on to Lexington, shouting alarms at houses on the way. At Lexington, he had already warned Hancock and Adams when Dawes arrived. His and Paul Revere’s night was just beginning.

Dawes was late because he had a longer route and a bit more trouble getting out of Boston. Like Paul Revere, he was a silversmith by trade and an active member of the Sons of Liberty, though the British thought him a mere hothead or a drunkard or even a simpleton. That was because Billy Dawes was able to mimic inebriation with such élan that even people who knew him were startled when he suddenly “sobered up” for any serious business at hand. British sentries always chuckled and let Billy Dawes pass, unaware that beneath the act was a cold customer with steely nerves and a dangerous temper.

William Dawes, Jr., in middle age after distinguished service in the Revolutionary War had made him a major and business savvy following it had made him a successful merchant.

He was a young man — just a few days over 30 and 11 years younger than Revere when the two separately rode out to Lexington — and was married to a stunning girl. When a British soldier leered at her one afternoon, Billy Dawes beat the man almost to death. Another time he had gotten into a fracas when trying to steal a cannon and had a cuff button driven into his wrist. The wound began to bother him, so he visited Dr. Warren who asked him how it had happened. Billy Dawes said nothing but simply leveled his gaze on the good doctor and smiled. That was the reason that on the night of April 18, when it really mattered, Warren had chosen Dawes to precede Paul Revere, and it was almost the only time the drunk act didn’t fool a sentry. By a stroke of luck, Billy recognized a soldier he had befriended, and the man let him through.

It was at 1:00 AM when the two left Lexington for Concord and were surprised by a rider coming up from behind. They were relieved to discover that the stranger was young Samuel Prescott, a Concord physician who had been courting a girl in Lexington and was heading home when he stumbled on this great adventure and eagerly joined it. Like Revere in the Charles River’s shadows and Dawes finding a friendly soldier to let him pass, Prescott turning up was yet another stroke of luck, because he was the only one of them who would see Concord that night. The trio ran into a British patrol that promptly captured Revere. Dawes fled but was thrown from his horse, which galloped away. Only Prescott escaped to ride hard on Concord and rouse the militia there. They would be waiting when the British came later that morning.

Major John Pitcairn was a Marine officer who had the unlucky job of leading the advance force toward Lexington. The men he was commanding did not know him well, and for a fateful instant, discipline broke down when the shooting started.

Nobody — not Revere, Dawes, Prescott, Hancock, Adams nor even the British soldiers and their officers — knew what might happen at the end of that long night of wild rides, daring escapes, and for the British grenadiers and light infantry a slogging march toward the unknown in a hostile country. There was no sense of inevitability, no premonition of something seismic waiting its time to occur and change the destinies of men and empires. A grenadier took Revere’s horse and considering Revere more a bother than a prize turned him loose in Lexington. There Paul Revere set himself the task of spiriting John Hancock’s trunk out of the village. He was in an upstairs room when he heard the fifes and drums and saw from a window the redcoats wheeling into position before the boys and men standing with fowling pieces and hunting muskets on Lexington Commons. He recognized the officer seemingly in charge, Major John Pitcairn, a jovial Scot who was a neighbor in Boston and was now shouting at the Lexington militia to lay down their arms and disperse. Revere pulled the trunk downstairs and was pushing it through militia ranks on the Commons and away to turn a corner when he heard a pistol snap. He turned to see a ballooning cloud of smoke and the unmistakable sound of pan flashes and musket reports from the British lines. Pitcairn had jerked his sword down, the signal to cease fire, but it hadn’t mattered.

A slogging march toward the unknown in a hostile country had come to this, something seismic after all, something to turn farmers into rebels and then into revolutionaries, to change the destinies of men and empires, beginning that April 19, 240 years ago.