A story in The California Star of April 10, 1847, seemed to confirm the worst rumors. A relief party had come upon a scene near Lake Truckee in the Sierra Nevada Mountains that horrified men hardened to the worst hardships. The snow was still thick on the ground, but the mutilated corpses throughout the camp were visible. An emaciated, deranged woman didn’t glance up or cease her labors. She was cutting the tongue out of a man’s mouth, having already broiled and eaten his heart. The newspaper reported that the rescuers later discovered that he was her husband.

The article in the Star told more, most of it worse. Mothers had eaten their children. Murders occurred when the strong killed and slaughtered the weak like livestock, and for the same fate as spitted-up steers. The rescuers, said the article, were shocked when people refused food because they preferred “putrid human flesh.” One of the emigrants, it was said, had taken a child to his bed one night, presumably for warmth. Yet he killed the boy and ate him before sunrise.

The lurid account in The California Star gave credence to rumors in the way a newspaper always does. Yet the story of rampant cannibalism committed by the stranded Donner Party was an exaggeration. The truth was shocking enough. Bad decisions and bad luck delayed the Donner Party’s arrival in the Sierra Nevadas. Trapped by heavy snow near Lake Truckee in November 1846, these people had to spend winter at the base of the pass that led to settlements in Alta California. Within days they exhausted their meager provisions. As it snowed without cease, they began to starve, and then to die. It was a terrifying state of affairs.

Such events would have been unimaginable just months before. As part of the epic westward migration to California and Oregon, they knew there would be risks and disappointments. They were hardly coddled people previously insulated from peril. Like many who undertook the journey, George Donner was not a reckless adventurer. He was a family man, several times over, having married twice and lost both wives in the course of moving from his native North Carolina to Illinois by way of Kentucky and Indiana.

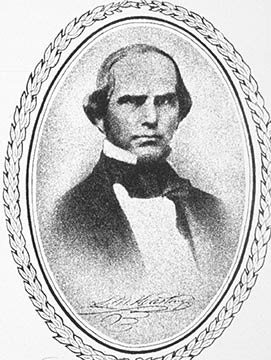

Donner settled in Sangamon County in 1828 where he prospered, 6’ tall and handsome, jovial and industrious. As he grew older, he became “Uncle George” to neighbors who treated him as a sage. He married Tamsen Dozier. The third Mrs. Donner was a Massachusetts schoolmarm fluent in French who painted passable pictures and had a touch of wanderlust to match George's. Only a few years after George and Tamsen had started his third family the siren song of California filled the air. They planned to go.

The song was irresistible for others as well. Another Springfield family joined the Donners. James Reed was an Irish-born immigrant who had come to America as a boy. Like George Donner he moved to Illinois, married a widow, and became a successful businessman. But the pioneer spirit stirred in him, and Reed like Donner sold off everything and outfitted wagons to move his family to Callie-for-ny-ay.

The Donner and Reed departures from Springfield on April 14, 1846, had the feel of a grand adventure. Diaries covering the opening days on the trail to Independence, Missouri, recorded buoyant optimism. Lighthearted sing-alongs around campfires continued on the Great Plains with fires fueled by buffalo chips that burned almost as well as wood.

They became part of a larger wagon train, a great river of canvas-covered oxen-drawn conveyances fed by dozens of tributaries like the Donners and Reeds. These enormous caravans were led by experienced men who knew the land and the places where sparse potable water could be found on it. They knew the indigenous people who could be sometimes dangerous, indifferent, or friendly. The Donners, Reeds, and all the rest were thus guided over the thousand miles through the valleys of the Platte, North Platte, and Sweetwater to the “parting of the ways” where the trail split to head for Oregon or California.

The latter route was the California Trail. The name misleads in that it suggests there was only one of them. Instead, there were numerous subsidiary paths blazed by men always looking for better, shorter, safer passages. More routes were created every migratory season. At Fort Bridger in the Wyoming country, the hottest news was about a shortcut through the Wasatch Mountains that could shave off anywhere from 300-400 of the remaining thousand miles to California. The legendary mountain man Jim Bridger— owner of the couple of ramshackle structures called a “fort” — touted the benefits of this route. It was called the “Hastings Cut-off” after the man who explored it, a pioneer guide named Lansford Hastings. Good ol’ Lansford, chirped Bridger, was at that very moment leading some time-saving emigrants through the Wasatch.

Contemplating the long dreary journey they had just completed, the family outfits that had clustered around the Donner and Reed nucleus were tempted to shorten their trip. On July 20 at Little Sandy River in Wyoming, they elected the old sage George Donner as their leader and separated from the large wagon train to head for the Hastings Cut-off. The newly minted “Donner Party” had less than 90 people: 34 adults (22 men and 12 women); 14 teenagers; 26 children ranging from toddlers to pre-teens; and 7 babies in their mother’s arms.

Lansford Hastings promoted a way to shorten the journey west. From Fort Bridger, his route headed south through the Wasatch Mountains rather than follow the traditional trails northward. The Donner Party elected to take it.

Despite their meager number, they had reason to be confident. Lansford Hastings, after all, had written a book — The Emigrant’s Guide to Oregon and California — judged by tenderfoots as indispensable for traversing the vast and trackless West. To follow the Hastings Cut-off, the Donner Party would leave the Oregon Trail at Fort Bridger and head southwest, cross the Wasatch Range, and move south of the Great Salt Lake. From there, the Cut-off looped up around the Stansbury Mountains and threaded through the Cedar Mountains to the Great Salt Desert. They would head around the south of the Ruby Mountains and then point northward to rejoin the California Trail. From there they would move toward the Humboldt River and then proceed to the Sierra Nevada. Those mountains were the final obstacle before the California settlements.

If it seems complicated, it was, and with many more complications than the Donner Party bargained for. The Hastings Cut-off was a taxing route for a trapper on a sure-footed horse. It was a lengthy logistical nightmare for inexperienced emigrants driving covered wagons and herds of livestock. Entering the Wasatch Range, the Donner Party had a taste of trouble early on when they reached the head of Weber Canyon. Here waited a nasty surprise: a large piece of paper had been folded and jammed into a split stick, a routine way to leave messages along a trail. This one was from Lansford Hastings, and it told anyone following to avoid Weber Canyon at all costs. His guiding duties for the party he had just led through Weber Canyon had included interesting diversions such as dismantling wagons to lower them, piece-by-piece, down sheer rock faces into deep gorges.

Hastings had roughly sketched an alternative route, but the Donner Party couldn't make sense of it. Reed and a companion hurried ahead to bring Hastings back as their guide. That journey convinced them that everything ahead was harrowing, but they at last reached Lansford Hastings. He was sympathetic but of little help. At most, he took Reed up to a promontory and made vague pointing gestures in the direction of the new route he recommended.

As they blazed this new trail, the Donner Party could only guess at how awful Weber Canyon was if this was supposed to be better. Fields of enormous boulders blocked the way, rivers ran under rocks so closely situated that a child couldn't squeeze through them, and seemingly harmless expanses of ground turned out to be pools of quicksand. By the time these people spilled out on the south shore of the Great Salt Lake, the shortcut that was supposed to consume days was stretching into weeks.

This was quite serious. Not only were they nearing the end of August, the extra time in the Wasatch and what lay beyond put a considerable dent in their provisions. Another surprise was the nature of the Great Salt Desert, which they had been told was about 40 miles across. It was twice that, and with nary a drop of water into the bargain. Families had to lighten loads by abandoning wagons, but everyone wasted time chasing half-crazed livestock and oxen wandering away in search of water.

By the time the Donner Party came back to the regular California Trail just west of where Elko, Nevada, now stands, the calendar had become a dangerous enemy. It was late September. Before them lay the difficult Humboldt Sink and then the Sierra Nevada.

They were also low on supplies, especially food. They knew that even stringent rationing would not stretch their food. In addition, though time was of the essence, the dwindling herds still with them weren’t fit for another mountain passage. Given those prospects, the Donner Party made two fateful decisions: first, a couple of men were dispatched to cross the Sierra Nevada and bring back food from the California settlements; second, the main party would rest for several days before taking on this last, daunting obstacle.

Both decisions were bad in a way. Sending Charles Stanton and William McCutchen to Sutter’s Fort for food was close to pointless. The distance wasn’t impossible, but the terrain was awful. Stanton and McCutchen’s journey was not only time consuming but the ability to bring back enough supplies to sustain the better part of a hundred people was limited. Nevertheless, the two men slogged doggedly toward Sutter’s Fort. Only Stanton would return; McCutchen became ill. Stanton packed provisions on mules. These were provided by the good-hearted Johann Sutter along with two Indian guides for help and company. Stanton immediately started back to the mountains.

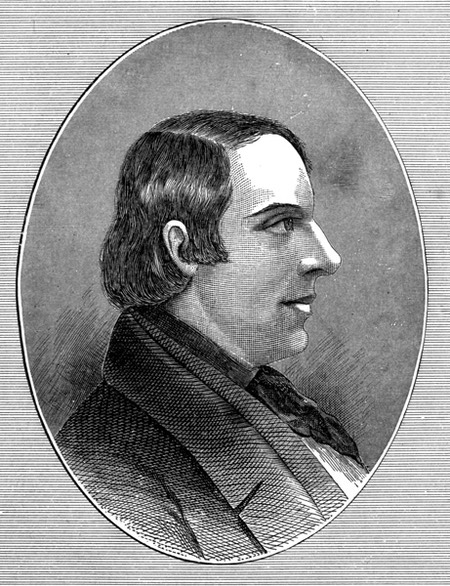

Charles T. Stanton was an intrepid member of the Donner Party whose journey for supplemental supplies levied a heavy physical toll, as he was to find out.

He rejoined the Donner Party in late October and found everyone’s mood a bit ugly. The second decision — to take a few days rest — was worse than pointless. It was fatal. The weather felt peculiar, and the skies suggested that the snows of late November could come earlier. Edgy, exhausted, frigid, and famished, the Donner Party had started quarreling about everything, including where and when to pitch nightly camps. On October 6, an argument over how to harness some oxen had escalated into a fistfight and then got worse. A popular and ordinarily jovial young man named John Snyder was beating James Reed with an axe handle when Reed sank his knife into Snyder’s chest, killing him. Snyder’s friends came close to stringing up Reed but were persuaded to “banish” him instead. He rode out on horseback with no weapons and a bit of food sneaked to him by his tearful wife. It was, everyone thought, a death sentence.

Afterward, a mild sense of panic permeated the group, and even the exultation over Stanton’s reappearance with food didn’t last long. It took only a few days for people climbing mountain trails in freezing temperatures to consume the supplemental provisions. Then, on October 31, it began to snow. The dirty skies had been an omen.

As they paused at Lake Truckee, they gauged themselves to be about 3 miles below the summit pass that began the descent to the California settlements. A few weeks earlier, reaching the pass would have taken a leisurely half-day. With snow falling more heavily by the minute, the pass might as well have been the moon. As the hours passed, one, two, three, five, and six feet of snow piled up, drifting ever higher, and making the pass ever more remote. The families turned back to some deserted cabins by the lake to wait out the storm. It is an indication of the bad feeling that had gripped this group that they eventually went into shelters rather far apart from one another. The Donner Camp ended up some six miles from the cabins. In any case, it was with great reluctance that anyone slaughtered livestock, especially oxen. The animals were the only way the Donner Party could get their wagons with all their worldly goods out of the mountains.

By November 12, the storm had only occasionally abated, and though the stranded emigrants had finally slaughtered their draft animals, the food had all but run out. Faced with starvation, a small group tried for the summit but soon came dragging back to the lake.

It continued to snow.

Boiling down hides to a gluey paste offered some sustenance, and the axle grease for the wagons had a lard base. But when people began to die, it was clear that spending winter at Lake Truckee would kill them all.

In mid-December, a youngster named Baylis Williams died of starvation, and five others died about the same time at the Donner camp on Alder Creek. These first deaths were heart-rending for everyone and had the effect of healing resentments with communal grief. But as the weeks wore on and more people succumbed, the people of the Donner Party didn’t so much become accustomed to death as indifferent to it, at least outside their own family circles. This was due inanition, a consequence of starvation along with derangement.

On December 16 the weather cleared. Twelve men (including the intrepid Stanton) and five women set out for the summit on makeshift snowshoes. Their intentions were mixed. The desperate need for some sort of volition as an act of survival was one motive for undertaking an impossible journey. Yet it also seems that several of the men left the camp to reduce the burden of their consuming its dwindling bit of food. Even so, two of the men were too weak to surmount snow drifts as high as 20 feet, and their turning back reduced the expedition’s number to 15.

These people would later be called the Forlorn Hope. It’s easy to see why. After clawing upward for a full day, they made camp and could still see the cabins not more than a half mile below. The next morning they persevered, and by superhuman effort and the luck of better weather, they were able to reach the summit.

The view was breathtaking. The lake sparkled under a brilliant sun, and the vista was boundless. One of the women heard someone mumble, “We are as near Heaven as we can get.”

The descent came as close to Hell as they could imagine. The sun caused Charles Stanton to go snow-blind, and on the morning of December 20, he remained sitting by the fire as the others prepared to drag themselves onward. Mary Graves, a pretty girl popular with everyone, asked him if he was ready to leave. “Yes,” he lied, “I’ll be along soon.” She looked back at him as she joined the others. She would never forget him slumping by the fire.

It began to snow again, and the rising wind turned it into a howling blizzard. A campfire of green wood smoked more than it burned, but it thawed the ice and suddenly disappeared through the snowy crust. The Forlorn Hope looked down a hole without a bottom and could hear a rushing stream far below. They had to keep their distance from campfires after that, which meant a dreary Christmas made all the more awful by memories of better days with stuffed goose and plum pudding. They had not had anything to eat in two days, and it was then that they began thinking the unthinkable.

A macabre lottery was organized with one piece of long paper designating the sacrifice who would save the others. Patrick Dolan, a laughing Irishman from Keokuk, Iowa, drew the long paper. Everyone sat silent at the prospect of killing this kindly man with his vague smile. Without a word, they dropped the matter. They avoided looking at one another.

That night, Patrick Dolan went out in the snow storm after shedding much of his clothing. There he died. Some would always think he had made the decision for everyone else. It was December 27, 1846. Patrick Dolan sustained them.

So it began. With the world covered by snow, with no game to shoot, and with no more hides to boil, the Forlorn Hope established what would later be called the Camp of Death, for it was there that they began to die. There, for two days, they ate the dead, and when two of their group — the Indian guides sent by Sutter — wandered away to die, they were killed for food, the only confirmed instances of murder for cannibalism.

Emaciated bodies of anything, whether animal or human, provide little nutrition, so the dead of the Forlorn Hope who had their limbs sawed off and eaten did little more than stave off death for the others. It turned out to be just barely enough. Taking advantage of occasional breaks in the weather, they found the descent a bit easier as they progressed, and friendly Indians gave them some food. On January 17 the remaining 2 men and all 5 women of the Forlorn Hope finally began arriving at the first waypoint on the path to Sutter’s Fort, a small place called Johnson’s Ranch.

Word immediately went out to other American settlements about what was happening in the mountains, but the people at Sutter’s Fort already suspected the worst. They knew about Stanton and McCutchen’s errand for provisions, of course, but on October 28 the “banished” James Reed had turned up after surviving an incredible journey to the settlements. He had rested only a couple of days before planning a rescue expedition to retrieve his wife and children. Yet the same weather that trapped the Donner Party in the mountains thwarted all efforts to reach them. Not until the arrival of the Forlorn Hope at Johnson’s Ranch was a realistic chance to find the stranded emigrants deemed possible. Soon several initiatives ranging from San Francisco to Sutter’s Fort were underway.

In all there would be four relief expeditions beginning in February and continuing into April 1847. All of them were lightly manned and took the great risk of being trapped in the Sierra Nevada, just as the Donner Party had. In mid-February the first relief party of 7 men reached what would ever after be called Donner Pass and descended to Lake Truckee, soon to be Lake Donner. They arrived at the cabins on February 19.

They found an eerie scene of deathly quiet. The snow had piled so high that the cabins were buried far under it. Only chimneys poked above the icy crust. The people clinging to life in the cabins under the snow had carved steps to the surface. Some of these makeshift stairways were 15-20 feet deep.

Eleven of the emigrants had died, and the emaciated survivors were in various stages of derangement. Nobody had resorted to cannibalism, though. The rescuers took 23 out of the camps, many of them the children, which was as many as they could manage and who were fit to travel. They also left as much food as they dared to spare. It was far too little, though, and seeing the relief party depart drained the fight out of those who remained. By the time the second relief party led by James Reed arrived on March 1, the wretched Donner Party, like the Forlorn Hope, had begun eating their dead.

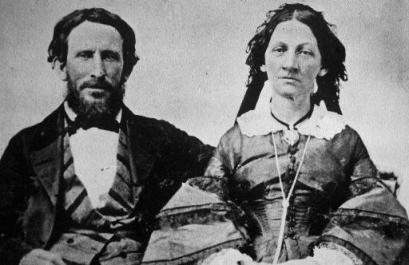

James and Margret Reed were reunited in February 1847 when the First Relief Party was rescuing her and several of their children away from Lake Donner. He was leading the Second Relief Party that encountered them. People recalled the family's reunion as “affecting."

Three more relief parties brought out the remaining survivors, and in the end more than half the Donner Party lived, a total of 48. The sensational accounts of cannibalism dominate the story now, and they were certainly a cause for consternation then, but the heroism and sacrifice of the adults in their hopeless situation awed the people who saved them, and humbled those who welcomed them back to civilization. Of the 48 survivors, 33 were children, a testament to fathers going without and starving mothers setting aside little scraps of food for special treats.

This 1866 photograph shows the site of the Donner family’s camp at Alder Creek. The trees were cut down 20 years earlier for firewood by the desparate people dying there. The “stumps” provide a gauge for the depth of the snow in the winter of 1846-47.

Included among the children were the 5 Donner daughters, now orphans. Their parents had died at Alder Creek, and the plight of the two youngest, ages 5 and 6, saddened everyone at Sutter’s Fort. The children waited for a relief party to bring them their mama. Finally someone told them that their parents were never coming down from the mountains. An elderly, childless couple — immigrants from Switzerland — took them in.

These two little girls were named Eliza and Georgia Donner, and at their new home with Christian and Maria Brunner they chased geese and chickens, helped with the chores, wept when they remembered their ordeal, and finally began to heal. They called Maria “grandma,” and they liked to sit in a large chair that could hold them both at the same time. “If you be good,” Maria Brunner told them in her sketchy English, “this be your home for good.”

As summer turned to fall and then winter, and then spring came again, the horrible days in the mountains retreated to the far corners of Eliza Donner’s memory. She resolved to be very good indeed. Nestled with her sister in the oversized chair, she was as near Heaven as she could be.