There was no “President’s Day” when the first man to hold the job was setting its precedents and shaping its protocols. Our title for today’s post doesn’t pertain to the first observation of the lamentable conflation of Washington’s and Lincoln’s birthdays into a “day” that has been shoved into the nearest Monday to lengthen the weekend — but don’t get us started on that. No, what follows relates to George Washington’s birthday and the unexpected controversies caused by the celebration of it. We’ve adapted it from Washington’s Circle, which is now available in paperback.

The resolution before the House of Representatives could not have been simpler or on the face of it less controversial. It was a measure to wish the president of the United States a happy birthday. Yet when the vote was tallied, an overwhelming majority rejected the innocuous measure and dealt the most revered man in America a resounding symbolic blow. Many in the House had grumbled the previous year, but nobody expected the enormous margin of 52-38 against the simple gesture of wishing returns of the day. As the country staged the usual birthday festivities, and the capital “celebrated with unexampled splendor,” the stark fact that 52 congressmen didn't want the president to have a “happy birthday” cast a shadow.

It might be of some surprise that this happened 220 years ago. The president was George Washington, the Congress was the fourth in the republic’s brief span of constitutional government, and the country was enjoying a lengthy period of prosperity and peace. Yet a growing number of people had become vigilant and wary by 1796. They had become afraid that behind the ceremonies and rituals of government — something they had seen evolving for seven years — lay dark plans to establish a monarchy and transform the republic into something like Great Britain. Of course, those who feared this had missed the measure of George Washington by miles, but at the same time their apprehensions were grounded in something more tangible than fevered talk of conspiracies. The process that culminated in the astonishing 52-38 vote that February had been long in developing, beginning with the apparently innocent business of how to manage the president’s social calendar. From such small matters, great controversies grew.

As he was ending his presidency, George Washington had aged far beyond his 64 years.

Establishing social protocols had troubled Washington’s advisors early in his presidency. How a president should handle social events seems frivolous on its face, but actually it wasn’t frivolous in the least. Accommodating anyone who appeared at Washington's office door meant constant interruptions that left him little time for real work. On the other hand, Washington worried that cutting off visits would make him seem aloof. Indiscriminately attending social functions would do more than consume enormous blocks of time, though. It ran the risk of unseemly familiarity. Washington was determined not to demean the presidency, no matter the political costs.

Everyone agreed that the dignity of the office required formal procedures to limit the President’s availability and govern his social schedule. The degree of formality, however, gave rise to differing opinions. Alexander Hamilton said Washington should keep as great a distance as possible between president and people. He should visit no one and only invite important government officials and distinguished citizens to dine. Hamilton recommended that Washington hold a weekly levee under formal rules of etiquette for dress and behavior. It would be open only to consequential people. As it happened, Washington would adopt this suggestion, even though it early showed how tin-eared Hamilton could be about governing a republic. Even the word “levee” brought to mind the trappings of royalty, and bringing to mind such things would gradually become a political problem for Washington as he listened more exclusively to Hamilton’s advice.

Even reasonable measures to establish the dignity of the presidency created the impression that rules for proper behavior and appropriate dress were pretentious. Because it was suddenly being associated with government, this sort of high-toned etiquette reminded people of royalty. Natural aristocrats were already American icons. Kings were objects of scorn because monarchy was an unearned honor. Worse, monarchy’s unmerited power was feared.

Washington’s natural dignity was itself destined to become a source of problems in light of these attitudes. He believed that formal dress and an elaborate retinue were the most obvious ways to create respect for the new government. He traveled the town in a large coach with six matching cream-colored horses, four servants, and two gentlemen on horseback. While admirers believed “he ought to have still more state, & time will convince the Country of the necessity, of it,” the jury in 1789 was very much out on the matter. As it happened, it was not out for long, and ultimately the verdict would not be favorable.

George Washington could do nothing about the public’s adulation, though it was worrisome early. Washington’s 1789 journey from Mount Vernon to New York had resembled a royal progress, and the intense excitement leading up to Washington’s inauguration caused artist John Trumbull, hardly a critic, to sniff at “the odour of incense” as the people went “through all the Popish grades of worship."

To his credit, Washington found this troubling too. As he arrived in New York City, the reception all but unnerved him, especially the multitude of watercraft in the harbor with snapping flags and banners as a barge brought him nearer and nearer to the roaring crowd on Manhattan. He had a premonition. The adoration was “pleasing” because it was so obviously sincere, but it created “sensations so painful” because he knew it could vanish overnight. As Washington rode that ornately decorated barge, he might have recalled the murmured warning to the Roman hero: All glory is fleeting.

_________________________________________

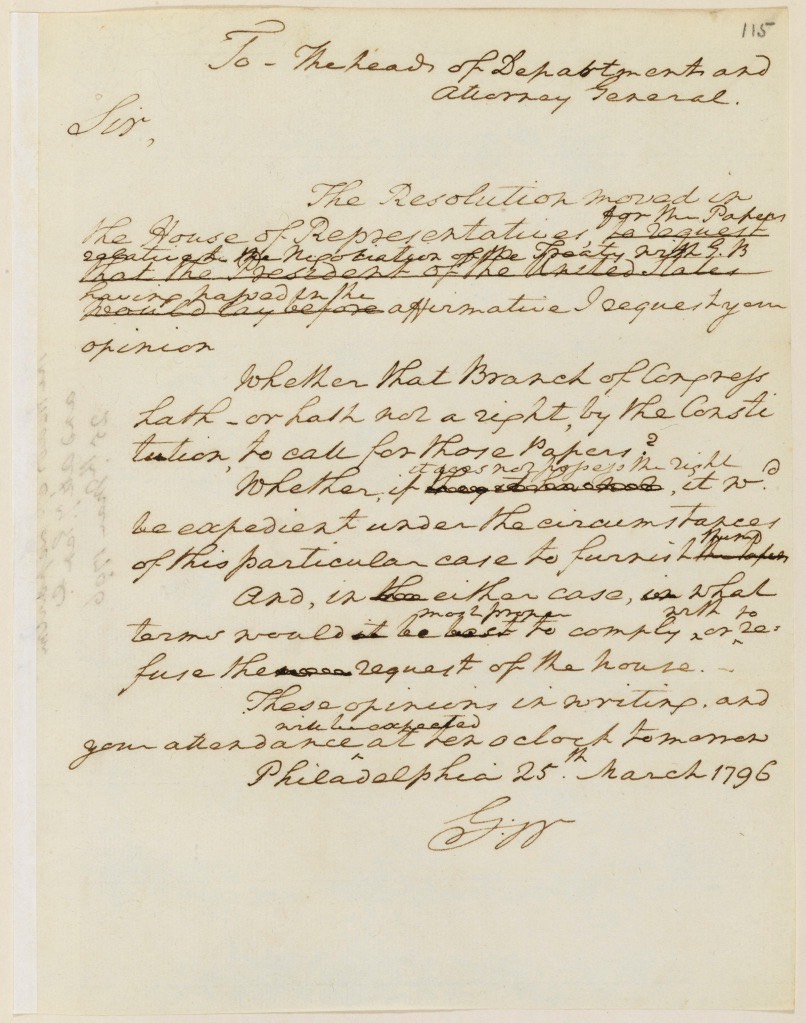

Just a month after the House of Representatives had refused to wish George Washington a happy birthday, it demanded that he surrender papers relating to the negotiation of Jay’s Treaty with Great Britain. His note to his cabinet requesting opinions on the propriety of this revealed his irritation over it, not by the wording but by his editing. In that spring of 1796, he was almost always irritated. (National Archives)

_______________________________________________________

Washington's formality and ostentation caused muted criticism in diaries and private letters at first, but eventually people afraid of kings and princes began to speak out. Finally Washington was in enough despair to open his mind to Thomas Jefferson about the growing rancor in the press. Attacks on him were a new development, and he struggled to understand them. After the lavish celebration of Washington's birthday one year in cities across the nation, Philip Freneau's National Gazette printed an anonymous letter that mocked them as a “monarchical farce.” Benjamin Franklin's grandson Benny Bache criticized the Washingtons’ levees in his Philadelphia General Advertiser. Another paper sneered that such customs came “from the uniform habits of Royalty.” A satire signed by “A Farmer” claimed that someone in Philadelphia mistook Washington's carriage and horses as those of George III’s son.

They would have been surprised to see life at the presidential residence in New York and later Philadelphia. As he did in Virginia, Washington kept to the same schedule each day. He rose early, usually before the servants, and ambled through the house. He inspected the stables, pulled up horses’ hooves to see about shoes, rubbed their noses, maybe pulled a carrot from his pocket for a treat, and watched with his emotionless blue eyes as it was crunched down. Back inside, he read newspapers and answered mail. He had been up for hours by the time he had breakfast with the family at 7:00. Then he worked with the secretaries and met appointments, one after another and seemingly without end. His exercise was either on horseback or a brisk walk in the neighborhood before the mid-afternoon dinner with his two families, the official one of secretaries ("the gentlemen of the household") and the other of his kin. Afterward, he returned to work until 8:00, had a light supper, and gathered again with the family. When conversation lagged, someone read aloud, often his private secretary Tobias Lear. The household was in bed by 10:00 at the latest.

The next morning was the same, as was the next. The levees, dinners, and impressive entourage were the public face of the president’s existence, but George Washington’s evenings were altogether different. Nelly Custis played the piano. Toby Lear read aloud. Washington's wife Martha sewed.

That was George Washington’s glamorous and regal life as the president of the United States. The public knew nothing of this, which was too bad. As he contemplated the mixed reaction to his 64th birthday that February 22 in 1796, Washington might have recalled the whispered warning: All glory is fleeting.