The land where this voice is heard is boundless

What follows has nothing to do with a talking terrapin, as those familiar with the Old Testament will know. It has, instead, to do with a universal truth of the human condition as revealed in two episodes involving Founding Fathers. The events occurred long before these men were wise sages guiding the fortunes of a new and vital country. Indeed, the stories that follow are reminders that all of us were once young, and that youth is never more golden than in retrospect. As children slog the tortured road to maturity, the days of youth are a time of wounded hearts, damaged pride, dashed hopes, and injuries so profound that you’re sure that all is lost, forever and a day. Old folks know these are common feelings experienced by everyone everywhere since apples hung in Eden, but that is of little help to the young. After all, to their thinking, they know what older people cannot know: the thrill of the world thawing away winter, trees going green, pulses racing, and the stinging pang that travels from heart to cellar in an instant at the sound of a voice or the glimpse of a face.

Allow us to introduce you, then, to George Washington, dashing militia colonel and man about town, who would find that his nose was too big for a certain lady. And to Thomas Jefferson, at an even younger age who, as a student at William & Mary, found the pages of scholarly texts blurring into the name of an angel he could not bring himself to talk to.

Almost every one of young George Washington’s romantic interests is obscure. Around 1749, possibly 1750, when he was eighteen, the lad made an ambiguous reference to a “Low Land Beauty” in a letter that itself has been a source of disagreement, specifically whether it was a letter at all or merely young Washington practicing letter writing. Nobody knows who the Low Land Beauty was, and the message in question is only an undated draft copy in a memorandum book that an editor surmised was written around 1749 or 1750 to someone named Robin, whom Washington calls a “dear friend.” A couple of years later, though, George developed an interest in sixteen-year-old Betsy Fauntleroy. By then, he was earning a bit of money as a surveyor, but Betsy’s father seems to have judged Washington’s prospects as too flimsy for him to sanction a courtship. The Fauntleroys were educated and prosperous Richmond County planters who likely considered themselves George’s betters. In any case, Betsy did not find George appealing.

In 1757, George Washington visited New York City and was said to have courted a young lady there, the result of having met a twenty-six-year-old heiress named Mary Philipse. By then, Washington’s exploits as a colonial militia officer on the Virginia frontier had made him moderately famous, and for that reason, as well as others, he would have been a catch. No evidence indicates as occasional speculation has, that George Washington’s towering height made him seem freakish to girls, or that his large hands put them off. Nor was he awkward or stumbling in conversation. He was tall, fair, handsome, confident, agile in dance, and fearless in combat. Being in his mid-twenties, however, made him something of an oddity in the marriage stakes of colonial America. Given life expectancy, and especially for men in the Washington family who were notoriously short-lived, someone pushing thirty in the mid-eighteenth century was entering middle age.

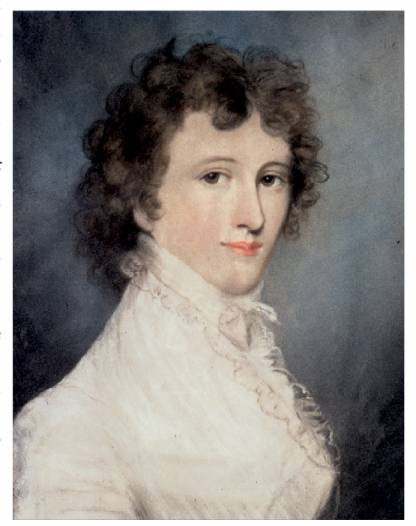

In New York, Washington stayed at the home of Beverley Robinson, whose marriage to Susannah Philipse had made him fabulously wealthy. Suzannah and her sister Mary, who went by the diminutive “Polly,” were rich beyond measure. Polly owned more than 50,000 acres of prime real estate on the Hudson River, which was enough to endear her to the most finicky suitor, and the dashing visitor from Virginia had to be impressed. Stories later claimed that Washington proposed to Polly Philipse, and perhaps he did. She was not only wealthy but fetching, buxom with rosy cheeks that dimpled when she smiled, though her habit of wearing a choker suggests that she was trying to hide a touch of goiter. Her real flaw, though, was willfulness. Money seems to have made her bossy, and the behavior probably reminded Washington of his mother, so even though he was likely attracted to Polly, her imperious streak could have made him pause.

Washington remained in New York City for the better part of three weeks, which was a long delay for a long trip. He took in the sights with female companions who are presumed to have been Susannah and Polly, suggesting that Washington was conducting something of a survey for a courtship, suitable chaperone included. Two outings were to an exhibit of small mechanical toys arranged in dioramas under the title “The Microcosm, or World in Miniature.” At this time in his life, Washington could be impetuous, even imprudent about women, as other events would soon prove. But if he did ask Polly to marry him, she obviously said no. One story says she didn’t like his nose, and on such weighty considerations, the fate of empires, not to mention hearts, was decided.

There can be some consolation in the fact that when first loves are unrequited, it’s often for the best. In that regard, George Washington could be regarded as spurned but lucky. During the Revolution, the Philipse women were steadfast Tories, and an idea of Polly’s personality comes from a remark made years afterward by her grandnephew. Responding to the observation that her fate would have been very different had she married George Washington, he said sharply that “she would have prevented” Washington from becoming “a traitor.”

Lucky us.

Polly Philipse

Peter Jefferson’s son had always been bookish. Still, like his father, Tom developed a passion for the outdoors, sunshine, riding fast horses perilously at their limit, and observing terrain along with the flora and fauna that lived on it. Like his father, he grew tall and athletic with a shock of red hair, a freckled complexion, blue eyes, and an open expression that matched his open mind. But Tom was different from his father, his mother, and his siblings. He kept to himself and spoke softly. His temper was mellow, and his tendency to withdraw and spend time by himself made him introspective and bashful.

It hampered his relations with girls, for the ordinarily cheerful fellow could be hopelessly somber in the company of a pretty lass. Simply put, Tom Jefferson was an awkward boy around girls, and he disguised a bashful nature by feigning aloofness. Girls almost always misinterpreted the act as indifference, or worse, disdain. Meanwhile, he kept to himself, wrote lousy poetry he never sent, lamented his loneliness to friends, and marveled at how his otherwise agile mind could be so dull and plodding when hobbled by soft eyes and a sunny smile.

Sad to say, young Jefferson’s complaint is universal among boys who daydream about dropping the perfectly crafted clever phrase. It’s always the one that’s sure to cause first downturned eyes and then slowly raised ones, newly alight with affection, just as dazzled as they are dazzling. Yet for most boys, these daydreams always go wrong, the phrase is stammered into a hopelessly stupid thing, and eyes will only stare, and if the girl is kind, will twinkle, not at all dazzled but at least amused. The dance is an old one. Girls know it by heart; boys learn it by heartache.

It’s pretty much what happened to young Thomas Jefferson. While a nineteen-year-old student at William & Mary in Williamsburg, he fell miserably in love. His letters to his friends lay bare a boy brimming with insecurities and muddled by daydreams that distracted him from his studies. Indeed, Tom took frequent breaks from dense legal treatises to confide in John Page, who followed the fashion of the time and saved letters. They consequently survive to tell the remarkable tale of an awkward courtship, for Jefferson wrote about the girl far more than he talked to her.

The cause of all this turmoil was Rebecca Burwell, whom Jefferson in his letters called R.B., sometimes Becca, and cryptically “Belinda,” a reference obscure to modern eyes. It was very probably an allusion to the charming beauty in Alexander Pope’s “The Rape of the Lock,” a satirical poem in which Belinda has a lock of her hair snipped and stolen from her (an archaic meaning of “rape” was abduction or theft). Such a lovesick device was poor enough, but when Tom was particularly wistful, he wrote of her as “Adnileb” (Belinda spelled backward). Yes.

To be fair to the smitten lad, by all accounts, he had good reason to be. At sixteen, Rebecca Burwell was a blooming rose with a ready smile and silvery laugh made all the more fetching by a touch of occasional melancholy. By the time Jefferson was pining for her, she had lost both parents, and being an orphan made her quietly religious, grateful for kindnesses, thoughtful to friends, and forgiving of enemies. She had legions of the former, almost none of the latter, and was at the age when young men came calling and bowed at parties to steal a dance. Tom Jefferson could dance, and when he could master his breath and calm his heart, he occasionally did so with “Belinda.”

Miss Burwell was in the care of a guardian, her mother’s brother William Nelson, who was a force in colonial Virginia’s politics. Jefferson would have had ample opportunity to see Rebecca in Williamsburg when Nelson was in the capital working. But Tom hadn’t the wit to talk to her, which is understandable, nor the sense to write to her, which is a shame. He could have told her some of the things he tediously said about her in letters to friend Page, and as his own Cyrano, won his own Roxanne’s heart. Rebecca seems to have been interested in him and revealed about as much of that interest as was proper for a young lady to show. For example, she gave Tom a small silhouette of herself, but the best he could manage was stammered thanks.

Meanwhile, he remained in agonizing suspense rather than risk a declaration of his feelings and have all his hopes dashed by the wrong answer. He told Page that if Rebecca did not return his affection, he would never love another girl all his life. He would leave Virginia and sail to distant lands in a ship named Rebecca where exotic scenes would cure his heart and steel his nerves. Page must have shaken his head in wonderment.

But soon enough, another letter from Jefferson came to John Page that recounted a tragedy. Tom had decided to declare his love to this girl, and the devil could take the hindmost. He spiffed himself up, settled himself down, and arrived at Raleigh Tavern’s Apollo Room with a well-rehearsed speech of cleverly crafted phrases. He bowed to beg a dance from Miss Burwell, and once he had her to himself, he opened his mouth to speak his piece. What then happened was genuinely horrifying. He heard his carefully fashioned hymn of love tumbling out in a jabbering jumble of words punctuated by long pauses. Rebecca said nothing. Tom then broke the silence with another recitation of stupidity. She was bewildered, he was humiliated, and he finally staggered her back to her chair and beat a humiliating retreat.

It is a testament to the durability of Thomas Jefferson’s optimism that he managed, over a bit of time with some therapeutic reflection, to recast this dreadful episode into a kind of comedy of errors that hadn’t turned out correctly because he had not made himself understood. He resolved to correct that situation, and his second meaningful conversation with Rebecca at least saw his mind and mouth working rationally — after a fashion. For on his second try at pitching woo, Jefferson elected to cast himself in the role of a lawyer as much as a suitor by confessing his love but also laying out terms for delaying marriage so he could travel to Europe and increase his fund of knowledge. Rebecca Burwell had been bewildered in the Apollo Room, but this second interview was singularly unromantic and, as it unfolded, more peculiar than Tom’s faltering disaster at Raleigh Tavern. She was too polite to laugh and too kind to mock. She calmly gave her answer.

Mary Ambler was Rebecca’s daughter, the child of her and Jack Ambler, who would marry John Marshall, destined to become Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Mary was said to greatly resemble her mother, which provides the reason for young Thomas Jefferson’s esteem.

In the Old Testament, chapter two of the “Song of Solomon” is a hymn praising the glories of spring, the time when the world thaws and trees go green. “For, lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone; The flowers appear on the earth; the time of the singing of birds is come, and the voice of the turtle is heard in our land.”

As we said at the outset, it’s not a turtle. It's a turtle dove, a small bird whose trilling coo is a plaintive plea for a mate. The land where this voice is annually heard is boundless, hemmed neither by seas nor hearts, a province of youth, no matter the age of the listener, for love’s magic transcends the counting of years and the passing of time.

Old people know this by heart; young people learn it by heartache.