The world had cracked open

One hundred thirteen years ago today, fires were still raging across San Francisco, which was the only thing that wasn't a surprise. Not that the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906 came out of the blue. Anyone who lived in the California coastal region was accustomed to the little shivers that occasionally rattled teacups and might jostle a sleeper awake in bed. But it had been a long time since a major quake. On October 21, 1868, one had caused a memorable minute of dancing structures and undulating streets that killed five people and left survivors rightly terrified. But its main impact had been across the Bay, and the years that followed were undisturbed by anything other than shimmers now and then, more conversation starters than heart-stoppers.

Doldrums encouraged complacency and led to innovations in insurance regarding earthquakes. In San Francisco, the great fear was fire, and with good reason. Six significant fires and countless minor blazes over the years had tried to burn the place down from the time it was the Golden Gate during the 1849 gold rush. And though by 1906 the city maintained 80 fire stations manned by 700 firefighters, nobody was much comforted by the pretense of preparedness. The firemen were marginally trained, and wood structures had always replaced razed ones, built quickly in willy-nilly fashion after conflagrations. Pervasive government graft had thwarted improvements in San Francisco's antiquated water supply system, making firefighters rely on corroded and often empty subterranean cisterns. Steam-powered pumper engines under-performed when they were tested, so tests were rarely held.

Insurance companies wrote policies in San Francisco, of course, but it was against the better judgment of underwriters who were only partly mollified by high premiums still not commensurate with the risks. Earthquakes, at least of the catastrophic kind, were rarer than fire and seemed less likely to happen at all.

For San Francisco, from its bawdy beginning to its seeming maturity as America's crown jewel of the Golden West, allowances were made. She was like a beautiful woman with coarse manners and corrupt habits, pretty but cheap, high-toned with a Grand Opera House and modern hotels but squalid with tenements that would have repelled slum dwellers anywhere else in the world. And though gaudy and garish, San Francisco was also home to decent, hard-working people who kept trim dwellings and led tidy lives. They too were part of the 400,000 living in an always open amusement park with stunning scenery and cosmopolitan flair. It was easy to overlook the blemishes when San Francisco flashed her smile, even if she sometimes got the shakes.

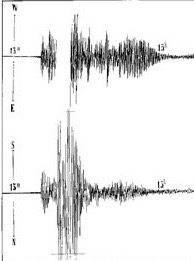

Nevertheless, in mid-April 1906, small groups of observers all over the world were a bit worried about the fetching girl as they gathered around machines and watched them with growing interest. They were seismologists, an old breed of newly invigorated scientists who had spent the last half of the nineteenth century developing instruments to track tectonic activity. They took their name from a term coined in the 1850s to describe what they were about, the word “seismos” from the Greek for earthquake. Their measuring tool was the seismograph, a contraption with an inked pen that traced the earth’s vibrations on scrolling graph paper. Staring at one was usually like watching paint dry.

Most of the world’s seismographs — less than a hundred in 1906 — were far from San Francisco. They also were not all of a standard design nor equally precise. But for what was about to happen, they didn't need to be. Whether sensitive or unsophisticated, they all picked up on the fact that something was going on at the eastern edge of the enormous Pacific Tectonic Plate, the one that abutted its North American counterpart along the California hinterland and coast. These seismologists saw this whether they were watching in Bombay, Edinburgh, Wellington, Vienna, or the scores of other small facilities spanning the globe.

Little hiccups jarred the pens scratching the rolling paper, an indication of more pronounced wave tremors than usual. From afar, they were detecting what is now believed to have unsettled many animals in San Francisco on April 17, the day before the event. Those creatures were perhaps hearing irritating and unnerving sound frequencies.

For whatever reason, horses neighed, whinnied, and stamped; dogs barked and whimpered; cats hissed and hid. Meanwhile, the little needle pens all over the world bounced a bit, rested, and bounced a bit more. Then, from Sitka to Rio de Janeiro to Cairo to Birmingham, seismograph pens began a wild dance, jerking up and down in a frenzy. They sounded like someone sanding a board as they pegged out above the graph’s baseline and plunged with spastic energy to peg out far below it. They darkened the paper with hideous inkblots, a Rorschach test for a wide-eyed world.

The seismologists knew it was happening, but people experiencing the event could not fathom it. About seven miles southwest of San Francisco, a little sliver of Pacific Ocean runs between a tiny igneous formation called Mussel Rock and the California coast. There the ocean covers the San Andreas Fault as it leaves land to run up under the entrance of San Francisco Bay north to Bonita Cove where it again reaches dry ground. It is the edge of the Pacific and North American tectonic plates. In mid-April, seismologists all over the world had been recording the activity there, and animals near it had heard these plates grind as they tried to dissipate stored up energy.

Dissipation did not work. At 5:12 AM on April 18, a jolt popped under the narrows off Muscle Rock with considerable force. The shock was felt and heard for miles. Less than a half a minute later the fault abruptly ruptured. It instantly generated a pressure wave of enormous power that exploded solid earth and vibrated air above it with such violence that people recalled feeling it as a physical presence.

The world had cracked open. The Pacific Plate sprung free. It moved forward to change something a quarter of a millennium in the making. With movement ordinarily measured as an inch per year creep, that minuscule metric was transformed into a powerful surge that pitched more than forty feet forward in a matter of seconds; when it could not lurch horizontally, it buckled and rose vertically. The shockwave from this commotion radiated out through the ground and rock, its speed ragged where the terrain was dense, swift where pliable. It became a growing circle of destruction expanding from Mussel Rock as the fault’s rupture sped north and south at 7000 miles per hour. Some 400,000 square miles, half of it below the Pacific Ocean, rattled and rolled in varying degrees of intensity.

It was the expanding pressure wave that came as a great destroyer. The ship Argo was about a hundred miles west of Point Reyes making way in calm water almost two miles deep, but the shockwave gave the vessel’s hull a sharp thump. The captain thought they had hit something.

As reports flew out of the places with the jumping needle pens, the earthquake had already finished its part in the destruction of San Francisco. Its work was as brief as it was brutal. The pressure–shock wave that charged into town from the West was an earthly tsunami. Streets rolled like the ocean. Tall buildings rocked to and fro, leaning far over avenues before drunkenly returning upright and finally crumbling into enormous piles of rubble. People lay mangled and crushed within it.

For about a minute this went on as sharp jolts jarred the ground with a capricious tempo, a ragged and deafening tattoo of the lowest bass — again felt as much as heard — and all underscored by a constant, growling rumble. The rippling, pitching streets soon were filled with terrified people, many partially clothed because of the hour, and mingling with vermin, especially rats, that were boiling out of the city’s sewers.

The shaking finally stopped, but the numerous aftershocks still to come were a grim companion for San Francisco's oldest and most feared nemesis: Fire. The earthquake had barely stopped when the first wisps of smoke rose above the settling clouds of dust and debris. The fires they signaled quickly found ample fuel in the rubble and wooden structures still standing. They began a relentless three-day march through block after city block in a place more defenseless than usual. The earthquake had broken and crushed water mains everywhere, and the blaze moved like a conquering army, its banners the dark billowing smoke towering over everything. By the time it stopped, the toll was almost 30,000 buildings.

Arnold Genthe’s famous picture of the relentless march of the fires

Such physical loss was staggering, but the human suffering by far exceeded the modest, official count of 500 deaths — an estimate later raised to 3000 — because the plight of survivors was worse than sobering. When the earthquake and fires were finished with San Francisco’s 400,000 people, more than half of them had nothing more than the clothes on their backs.

It was an awful time, a dark hour so devoid of anything but devastation and hopelessness that it was easy to bow to evil and surrender to fatalism. To be sure, the catastrophe brought out the worst of those already inclined to mischief or graver, malevolent crimes. But it also gave rise to the best in people. Thousands of large and small acts of nobility and compassion affirmed kindness, empathy, and honor.

Local authorities and the United States Army preserved order and provided essential services, including food, water, medical treatment, and public safety. San Francisco's chronically corrupt government unexpectedly stripped away layers of dishonesty to reveal a capacity for selfless public service and surprising competence.

Banks established ad hoc arrangements with the US Mint to resuscitate a shattered economy that within weeks was transfusing life into minor and major rebuilding projects and giving hope as well as work to people in desperate need of both. The postal service delivered letters anywhere, ignoring the absence of postage stamps to speed calming messages to an anxious world fretting over loved ones in the rubble.

Donations began arriving from cities, towns, and villages across America and beyond. Corporate fundraising coincided with community bake sales and hastily assembled church bazaars eager to match millions with pennies, nickels, and dimes that grew, town-by-town, into dollars.

And when San Francisco's telegraphic communication with the outside world was restored, there came to it an extraordinary, historic message. The remarkable nature of San Francisco’s twin catastrophes of earthquake and fire gave insurance companies a variety of ways to avoid their obligations. The most obvious was to say that the quake had caused losses insured against fire and consequently were not covered. Some firms pulled this trick by offering to pay deeply discounted claims, some slashed by as much as 70%. This low dodge was made easier by the fire having destroyed most policy documents.

And yet, something else happened too. One of those dancing needle pens had been on a seismograph in England, which meant that within minutes of the earthquake, underwriters at Lloyd’s were aware of the California catastrophe. The man at Lloyd's responsible for underwriting earthquake insurance in San Francisco was an already legendary figure named Cuthbert Eden Heath, an innovative visionary who could have been the model for the unflappable Englishman Jules Verne created as Phileas Fogg.

Cuthbert Eden Heath

Heath was virtually deaf — the condition had barred him from his family’s tradition of serving in the Royal Navy — but the uproar at Lloyd's over the horrible news coming from California did not need sound for emphasis. Even as the fires were raging on the other side of the world, Heath knew the cost would be monstrous. He also knew that thousands of people eager to game the system by bilking insurers would be sly and resourceful. These were all things to weigh as he recalled how he had persuaded his syndicate to insure San Francisco aggressively. It accounted for about 20% of all the losses there.

The coolness with which Cuthbert Heath took up his pen was matched only by the seismic nature of the telegraph message he wordlessly handed to one of Lloyd's red-liveried “waiters” for immediate dispatch. It was as seismic, in fact, as the message delivered by the San Andreas Fault on April 18. "Pay all your policyholders in full, irrespective of the terms of their policies."

Pay all policyholders in full. Like the radiating circle of power moving out from Mussel Rock, a thousand such deeds became a power of their own, equally irresistible, but with the advantage of being durably constructive and eternally inspiring. Cuthbert Heath sent his telegram, the housewife in Billings reached for her cake pan, the school kid in Augusta dropped a penny in a tin can labeled “San Francisco relief" — all of them, in their way, echoing the sentiment behind the historic message: pay all policyholders in full.

Little wonder that San Francisco, from the rubble, flashed her smile.