Almost sixty years ago, Leonard Read's essay "I, Pencil" appeared in The Freeman. It is an expository masterpiece that traces the family tree of a pencil to show the multiplicity of technologies and varieties of human effort required to produce it. But Read's kicker is how the people involved perform their varied functions — nurturing forests, chopping down trees, processing lumber, shipping it, manufacturing components, assembling them — with most unaware that they are helping to make a pencil. No mastermind has conjured a grand plan to guide them. The process sorts itself out because of the self-interest of individuals. Friedrich A. Hayek described it as a process that "will make the individuals do the desirable things without anyone having to tell them what to do." Thus markets and manufacturing naturally solve the "problem of the utilization of knowledge not given to anyone in its totality."

Of course, the system only works if populated by innovative, resourceful people — those described as "self-starters" by entrepreneurial types — which is perhaps why it has always worked so well in America, a country brimming with self-starters. A couple of years ago, our little essay about one such American with a long list of achievements appeared on the anniversary of a memorable one. Since this Tuesday, February 28, marks the 190th anniversary of the founding of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the similarities of that corporate decision to the story of Read's pencil are striking: from one act of innovation would spring hundreds and thousands more, in part thanks to the subject of our post. We've adapted it accordingly for the occasion.

________

On August 28, 1830, the first American-built steam locomotive carried forty-two passengers on a round-trip a little under thirty miles between Baltimore and Ellicott's Mills. The little contraption hardly merited the label “locomotive” because the “Tom Thumb,” as it was later named, lived down to that moniker for its resemblance to the tiny imp of folklore. It had proved quite an imp itself as mechanical failures dogged it from its inception while thieves routinely broke into its construction shed to pilfer parts and vandals broke what they couldn't carry away.

The Tom Thumb wasn’t built on commission either, and the people it was meant to impress were skeptical about the basic idea behind it, meaning the use of pressurized steam for propulsion. People all over the world had been building steam engines for years, but they were halting and unpredictable things for mobile operations, often too weak to manage slight grades and dangerous to boot, exploding when valves stuck or faulty boilers like tea kettles surrendered to just a bit too much pressure. The directors of the recently hatched Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (already jauntily referring to itself as “the B & O”) had laid down a railroad alright, which meant they had merely put rails on a road. But they were relying on the dependable old harnessed horse for their horsepower. Horses struggled on grades, but they seldom exploded.

The Tom Thumb’s builder was also its inventor, and he had never built a steam-powered mobile machine in his life. It was a supreme act of faith when the directors of the B & O Railroad climbed aboard a small open passenger car with their guests for a ride that might not get started and was likely to strand them somewhere along the way to and from their destination. It was an even greater act of courage for the five men who climbed aboard the little engine’s platform with its hissing boiler, tubing fashioned from rifle barrels, a load of coal on one end, and a cask of water on the other. The sixth man, the one at the levers and throttles of the Tom Thumb had had plenty of his inventions blow up. He was intent, however, on selling steam.

The Tom Thumb was a feat of improvisation that was never meant to be anything other than a demonstration model. The little locomotive was scrapped after a couple of years despite its historic significance, but Peter Cooper wouldn’t have minded. He and the country were in too much of a hurry to be sentimental.

So the little engine that could wasn’t much to look at, but almost everything mechanical that Peter Cooper put together was that way. Cooper wasn’t an engineer by training, and he usually designed from intuition, which made him a sketchy if gifted gadgeteer. He was the kind of man who grabbed odds and ends, a length of wire, a stray bit of metal, and went to hammering while stopping to ponder. He took a thing apart, pounded something into shape, wedging another thing for a tight fit, and staged dozens of trials with just as many errors until he had a reasonably functional something, say a washing machine or whatever else was a pressing need at the moment. The Tom Thumb was the pressing need for the moment, and its 39-year-old inventor was a prosperous businessman who approached inventions as hobbies.

He always had that attitude. Born in 1791, he was the fifth child of a large and loving family that liked to tell the story of how the boy came by his name. His father, a staunch Methodist, was walking down Broadway one evening when a clear but soft voice sounded in his head: “Name him Peter.” For a staunch Methodist, that was an instruction rather than a suggestion, and John Cooper complied with it without question. Thus God christened the boy they named Peter, and he repaid the compliment by always being lighthearted and industrious.

The Coopers were enterprising people who believed in improvement, and Peter certainly learned the value of personal progress, but he lived in a happier time when education was tailored to talent rather than seen as an obligatory ticket for everyone to get punched. Peter’s brother, for instance, became a respected physician, but young Peter showed an early aptitude for craftsmanship — “good with his hands” as people put it — and a way of understanding machinery that for him stripped mechanical things of their mysteries. There was nothing about this that classed him as an inferior within the family or the wider world. He liked the outdoors and daydreamed at studies, so he went to work in his father’s hat factory when still a little boy. His first job was pulling rabbit fur for the stylish hats then in fashion. Honest labor was a badge of honor.

And in his spare time, he investigated the world and tinkered with things. The world could be more than he bargained for. When he was four, he fell from a joist in a house under construction, struck his head on an iron kettle, and opened his forehead to the bone. The scar was visible for the rest of his life. It was only his first. A few years later he was working on a project with an older boy who accidentally sliced Peter’s face open with a knife. His mouth was always a bit crooked after that. He was splitting wood and caught his ax on a clothesline, causing the blade to crack his skull with “the deepest and most dangerous wound I ever had.” He fell out of a cherry tree and knocked out a tooth. He was climbing a prickly pear to get a better look at a finch’s hatchlings when a thorn caused him to smash his hand into a hornets’ nest.

He wore bandages as badges of exploration, but he also began to tinker. When still a boy, he built a “washing machine” that improved his mother’s traditional clothes churn by mechanizing it with cranks and gears. He cut up old shoes to see how they were put together, saved up for awls and leather, and soon became a self-taught cobbler of such proficiency that he was making fashionable footwear for his sisters, work boots for himself, and bedroom slippers for his mother.

Peter’s father always planned for big successes but often had to cope with seemingly inevitable setbacks. The hat factory fell victim to this trend in the family’s fortunes, and 17-year-old Peter cheerfully apprenticed to a coach maker by nothing more than a handshake, reflecting a life-long loathing of how lawyers could complicate the most basic transactions between people. He had no time for that kind of hurdle, and when he saw a way to make mortised carriage hubs with machinery rather than laboriously by hand, he let his employer set the price for the invention. Rather than haggle, Cooper put money aside, lived frugally, and married a girl he loved and would adore for the rest of his life. Coming home from work early one afternoon, he found her wearily rocking their newborn to sleep. Cooper pulled out his toolbox and in no time had modified a cradle with spring-operated clockwork to rock the baby, shoo away flies, and turn a small music box. She loved him for the rest of her life too.

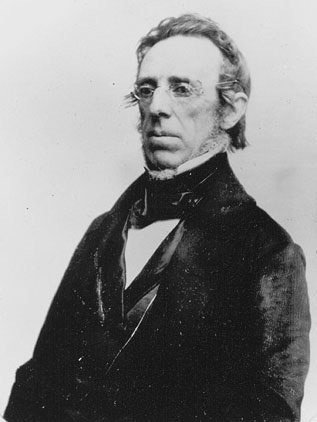

Peter Cooper

Sarah Cooper understood her husband entirely, but it was hard for other people to take the measure of this restless soul who was nonetheless unerringly dependable. His inventions were hobbies, though often with a purpose. But he made a living as the owner of a burgeoning grocery business. Then he came up with a better process for making glue that was efficient and profitable. Proceeds from Cooper’s glue factory in New York helped him buy real estate in locales the blinkered saw as unpromising, such as the Canton district in Baltimore where he noticed that a new corporation styling itself the B & O Railroad would need iron rails. His Canton foundry would take off, he reckoned, if the B & O would lose the horses and adopt steam-powered locomotives. He did some reading and reached for his toolbox.

Cooper was to make a fortune several times over from his expanding foundry and his profitable glue factories, but he never lost the spirit of the tinkerer, and he ultimately turned that spirit to something more durable than inventions of the moment. He was appalled by the way poverty and ignorance wasted human capital, so he bought a city block in lower Manhattan and constructed on it a large building to house a free technical school for a set number of qualified annual applicants of both sexes and all races. It also included a cultural center for public lectures and an excellent library that remained open until 10:00 PM so conscientious laborers could study after their workday. The Cooper Union opened in 1859 and among its first notable events was a political address by a rawboned Illinois lawyer to New York’s social and intellectual elite. Both Abraham Lincoln and the Cooper Union had remarkable futures ahead of them.

The Tom Thumb’s 28-mile roundtrip that August day in 1830 took a total of two hours and nine minutes, but as a linear event it could be judged as endless, only a waypoint in Peter Cooper’s long and exciting journey. For him, it ended in 1883 when he was 92, but he was of a type that would live on in Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse and Henry Ford and Steve Jobs. There was in Cooper’s beginning and at his end and in all the years between a perfect symbiosis with the bewildering country called America.

He was more than an American archetype. He was something closer to America itself as a shining idea intent on making things better than when found. Like his country, Cooper was careful about money, morals, manners, and means, but he was entirely heedless about obstacles and dangers in achieving a goal. Like America, Cooper was mindful of expenses but counted no costs.

It was the sort of thing about the country and the people in it that has always puzzled foreigners. His companions that August day on the Tom Thumb were certainly nervous as he pushed forward the makeshift throttle and the little engine began to roll. Who knew but that it might blow up? Peter Cooper kept his eyes on the rails ahead, his crooked mouth set in a grin over the grand adventure of it all.

His country was like that.