The words “New York City” or “Manhattan” summon images of a bustling metropolis with huge buildings and street canyons that span like a spiderweb from shore to shore, east and west and north and south. Yet New York in the 1780s was a provincial village compared to European cities. London had a population of some 750,000 people, and Paris about 600,000. New York contained some 30,000 people with almost everyone living on the southern part of Manhattan. The rest of the island was covered in farms and dense woods occasionally interrupted by dirt roads.

Yet, on September 13, 1788, the Confederation Congress — the one that governed the United States before the Constitution — officially designated New York City as the capital of the United States. It was one of the Congress’s last official acts, and the language of the proclamation, like much else the Confederation had been doing, had the ring of an afterthought about it. It merely stated that “the present seat of Congress [shall be] the place for commencing proceedings under the said constitution.”

September 13 two hundred thirty years ago was a Saturday, and the Congress was busy with a variety of chores that day that had become tedious. The main one concerned the disposition of American prisoners being held in Algiers by Barbary pirates and how possibly to ransom them. (Among the many woes of the Confederation government was the miserable state of its finances.) A sense of futility had plagued this unicameral legislature since its inception during the Revolution, and the pervasive ineffectiveness of deliberations had made its sessions lightly attended for years. The situation had worsened as it became apparent to members that they were guiding a rudderless ship about to be boarded by an entirely new crew. The recent ratification of the Constitution would mean a new legislature, an executive, and a judiciary. The Confederation Congress was leaving some delightful gifts for its replacement: an empty treasury, a mountain of debt, a frail Union of quarreling states, an international reputation for fecklessness, and New York City for a national capital.

The United States government under the Articles of Confederation had been operating in New York City for several years, the one stable aspect of what had been a wandering establishment during the Revolution. Initially in Philadelphia, but run out of there by the British occupation in 1777, it had set up shop in Annapolis for a while before trying to resume operations in Philadelphia, only to have an American military mutiny put everyone in flight again. That was how the government had come to New York, like a refugee, and after settling in, some decided the place wasn't half bad. Others weren't so sure.

Commercially New York had the advantages of an accessible harbor connected to the interior by the Hudson River. Culturally it had access to the grandest traditions that Europe could export, including a diverse population of immigrants. But it lagged behind Philadelphia in the arts and in architecture, and given an excuse, it could also be worse than unruly.

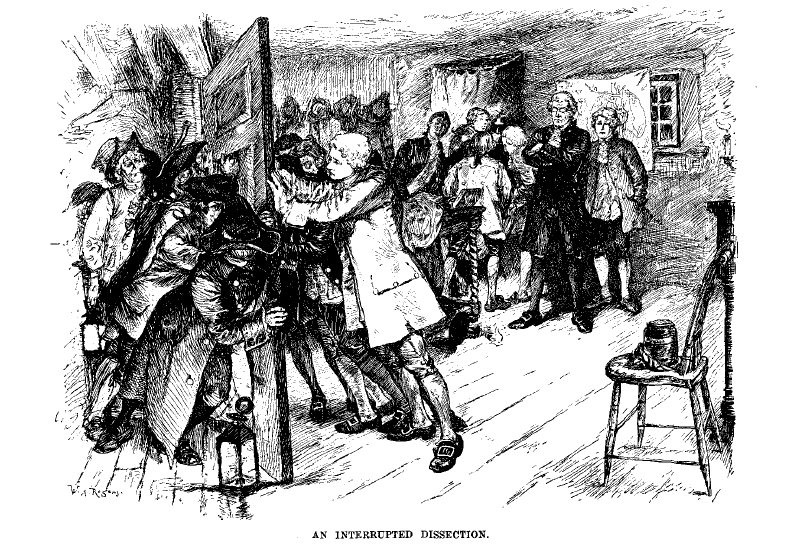

The riot, in fact, was a venerable tradition in New York City for expressing displeasure over just about anything. In 1788, a full-fledged incident featured highly accurate rock-throwing and left several buildings wrecked. It started after boys playing near a hospital caught sight of dismembered body parts and alerted the community. In no time at all a rapidly ginned-up rumor told how medical students were robbing graves for anatomy lessons. Authorities locked up some students, primarily to protect them, but a series of riots broke out for several days and finally focused on the jail. Governor George Clinton called out the militia and in the company of prominent citizens personally led the troops to protect the prisoners.

A contemporary engraving depicted a relatively calmer interlude during the mayhem

The mob was singularly unimpressed. Rioters greeted the august assemblage with hurled rocks, brickbats, and curses. John Jay and Baron Friedrich von Steuben suffered nasty head wounds, and a rock grazed Clinton's arm. Although under orders not to fire, the militia reacted to the growing melee by leveling muskets and sending two volleys into the crowd. The shots persuaded the mob the fun was over but at the cost of three people killed. As the chastened crowd dispersed, Jay, knocked cold, was taken back to his house where he was bedridden for days with his face black and blue and eyes swollen shut.

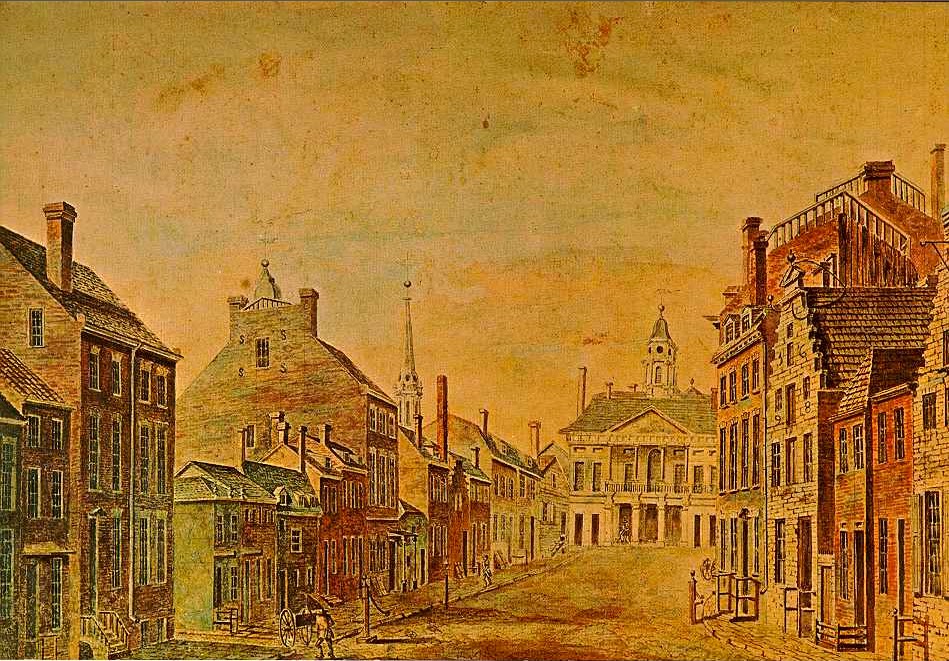

Meeting in the shadow of the infamous “Doctor Riots,” the new government contemplated its newly designated capital with every reason to feel a bit uneasy. Even when calm, New York’s chronic shabbiness severely limited its charms in the cold light of day. The city was a patchwork of overlapping communities that had grown haphazardly out of the Dutch village founded in the previous century. Fires during the British occupation in the Revolutionary War had devastated lower Manhattan, but rebuilding had not resulted in renovation. The streets were “badly paved, very dirty & narrow as well as crooked, & filled up with a strange variety of wooden & Stone & brick Houses full of Hogs and mud.” One can presume that it was the streets, not the houses, filled with hogs and mud. Residents complained of the incessant noise of the place, including livestock sounds such as squealing hogs chased by howling dogs.

New York City was also a medley of bad odors. Many streets were too narrow for sidewalks, and in defiance of city ordinances, poorer inhabitants threw garbage into the streets. The sewage system was primitive, with much waste disposed of by “slaves, a long line of whom might be seen late at night winding their way to the river, each with a tub on his head.” That was in the more fastidious parts of town. Elsewhere people emptied slop jars of their “night soil” onto unpaved streets where an abundance of horse manure and urine was churned into a mixture that reeked of ammonia and excrement. Street lamps had been put up here and there, but they were seldom lit. It was perhaps nicer, if not always safer, to keep the place in the dark.

On this sketchy stage, New York City’s fathers were determined to make permanent the city’s designation as the United States capital. City Hall was to be dubbed Federal Hall after extensive remodeling supervised by Pierre L'Enfant, a young French engineer who had served the American cause in the war. George Washington knew him, pronouncing his name after their first meeting as “Monsieur Lanfang.” New Yorkers paying the bills for his designs came to know him all too well and would conjure ever more colorful names for him. L’Enfant’s Federal Hall project got off to a slow start and proceeded even more slowly as time went on. It was a warning about L’Enfant’s methods, which missed deadlines while busting budgets.

Federal Hall

At least Federal Hall had the advantage of looking expensive. L’Enfant used native materials, fashioning the hearths in the Senate chamber on the second floor from American marble. The capitals on pilasters featured American symbols, and a frieze on the building’s exterior was much admired for its artistry and inventiveness. The eagle that was supposed to cap the effect would not be finished when Congress first convened, but it was in place when George Washington appeared for his inauguration. With its new interior plan, the building placed the House of Representatives and galleries in an octagonal room on the ground floor. The Senate chamber on the second floor needed no gallery because the Senate had decided to conduct closed sessions.

To greet President-Elect George Washington, New York planned an epic spectacle. Washington crossed Newark Bay on April 23, 1789, in an elaborately decorated barge sporting a red canopy with boats large and small following behind. Musicians and singers aboard the barge kept up a serenade as it passed Staten Island where batteries fired a 13-gun salute. (Only eleven states had ratified the Constitution so far, but there was optimism about the other two in the fullness of time.) Another barge had departed from lower Manhattan with an official escort of dignitaries that included Henry Knox and John Jay, a high level of coordination synchronizing the movement of the two crafts. Thousands waited at the tip of the island, and another battery fired a 13-gun salute as Washington’s barge approached. Every church bell in New York City began tolling. Governor Clinton extended the official welcome over the din of cheers and bells. Clinton ended with the offer of an honor guard to escort Washington to his lodgings. “You will give yourself no further trouble,” Washington replied, “as the affection of my fellow-citizens is all the guard I want.” That day, it was all the guard he needed.

The city fathers were encouraged that this grand opening for the new government would permanently secure the place as the nation’s capital. And for a while, it seemed inertia alone would do its part to keep the government in place. Yet, it was not to be. Forces quite beyond the control of anyone rooting for Manhattan came into play to pry the prize from New York. That very summer Alexander Hamilton traded the permanent site of the nation’s capital in exchange for his complicated plan to rescue the nation’s finances. Proponents for another place for the capital opened the residency question in Congress.

The residency bargain considerably dampened New York’s optimism. On July 1, 1789, the Senate passed a bill establishing the temporary capital in Philadelphia for ten years and then moving the permanent one to a place of George Washington's choosing on the Potomac River. The vote was close, however, at 14-12, which gave its opponents — New Englanders along with New Yorkers — hope in the lower chamber. When the bill arrived in the House, those New Englanders joined New York efforts to cut out Philadelphia as the temporary capital and make it New York instead, buying time for the possibility that inertia might work its magic after all. Enterprising congressmen filled the galleries with New York belles, “as much as to say, as you Vote, so will we smile.” Virginian Richard Henry Lee chuckled over the tactic as “a severe trial for susceptible minds – And very unfair (if I may say that Ladies can do any thing unfair) whilst the Abundant beauty of Philadelphia had not an equal opportunity of shewing its wishes.”

Despite such lighthearted antics, New Yorkers were keenly unhappy about losing the capital as a permanent fixture. The city had spent a fortune on plans for a new presidential mansion overlooking the Battery, convinced that such a project would anchor the government in New York. Newspaper editorials extolled the virtues of the city and denigrated the rural primitivism of the Potomac.

When the day came the following summer for the Washingtons to leave New York, the city’s funereal mood was a stark contrast to the raucous celebrations of a short sixteen months earlier. New Yorkers barely reconciled to losing the capital were disconsolate over the reality that George Washington would never have a reason to visit them again. On August 30, 1790, when the presidential barge pushed away from the dock, a large crowd of citizens and dignitaries gathered, but muffled city noises and water slapping against the bulkhead were the only sounds. “Not a word was heard,” Abigail Adams marveled. Rather, each man “took off his Hat bowd [sic] and retired.” For the people who had built government offices and bent over backward with other ingratiating gestures, it was the end of an era, the time when the only guard the president had needed was the affection of his fellow citizens.