Sam Houston had been in Gonzales only 48 hours when the news arrived about the Alamo. It was gruesome: no prisoners taken, every defender dead, corpses stacked like cordwood and burned. The bearer of these tidings was Susanna Dickinson, now widowed, her husband among the slain. What happened in Béxar had scarred them forever. Susanna handed Houston a letter from President-General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. It decreed that the fate of the foolhardy rebels he had slaughtered at the Alamo was to be the fate of all Texians until they surrendered their arms and submitted to his authority.

Thus was made plain what Houston had suspected all along. Months before he had predicted what everyone else said was impossible. Everyone else had thought the Texas rebellion against Mexico would have time to organize itself. After all, running Mexican authority out of Béxar in December was fortunate in its timing. It was received wisdom that no Mexican army would appear until late spring at the earliest, and they began to suspect that appointing Sam Houston the commander-in-chief of Texian forces had been a mistake. He was acting like an old woman.

Yet Houston was vindicated when the Mexican humiliation at Béxar enraged Santa Anna. Against all received wisdom, the President-General pounded north to suppress the Texian rebellion in the worst season of the year. Once at his task, he would commit unimaginable acts of brutality to intimidate Texas into submission. His march in the winter of 1835-36 across forbidding terrain cost him almost half of his 5000-man army, but by late February he was nearing Béxar and the Texians had retreated into the Alamo. Their leader was William B. Travis who, along with James Fannin some fifty miles downriver at Goliad, had resolved to block the Mexican army’s march on the eastern settlements. Houston warned that these remote and undermanned outposts were doomed, and he had tried to pull Travis back to save not only his men but his weapons. Travis had disobeyed Houston, and to Houston’s dismay his courier ordering the withdrawal, the legendary Jim Bowie, had thrown in with the jaunty colonel.

The news from Travis that the Alamo was besieged by thousands of Mexican soldiers instantly began to drive events, and Houston was barely able to stop a mad rush to Béxar aimed at reinforcing the tiny garrison. He kept to himself his conviction that the Alamo was beyond saving and that anyone running to help it would be lost too. His only certainty was that Texas would need every man and boy it could muster in the coming fury. At Washington (later named Washington-on-the-Brazos), the revolutionaries grudgingly took his advice to declare independence and establish an ad interim government that would give shape and substance to their insurrection. The convention forming the new government also reappointed Houston commander-in-chief, though few were happy about it, including Sam Houston. Ad-interim president David Burnet thought Houston was a profane drunkard who talked big but acted small, while Houston thought Burnet was a back-biting hypocrite whose pretensions to statesmanship only slightly masked a petty politician. Most members of the new government suspected that Sam Houston was worse than cautious. Rather, he seemed timid about tactics and reluctant to fight on any ground at any time. The crisis seemed to call for a daring William Travis and a steadfast James Fannin.

Houston left Washington for Gonzales some 100 miles to the southwest, ostensibly to organize the relief of the Alamo. He arrived on March 11 and was secretly sorry to hear that thirty courageous Gonzales men had already gone to Béxar. The remaining militiamen, less than 400 in number, were eager to head there too, but Houston stalled them. They were in no shape to fight Santa Anna, but he didn't tell them that. He put on an act of preparing for a march, including sending out scouts to reconnoiter the countryside. The chief of those scouts, Erastus “Deaf” Smith, found Susanna Dickinson and her daughter, along with Travis’s slave Joe and brought them into Gonzales on March 13. The stunned village learned that these people were the Alamo’s only survivors.

Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna

Houston did some alarming reckoning. The Alamo had fallen a full week earlier, which meant that Santa Anna had been given more than enough time to cover the fifty miles between Béxar and Gonzalez. That was just fine with the Texian army, such as it now existed, for the men wanted to avenge the Alamo as soon as possible. They were therefore astonished to learn that Houston intended to burn Gonzales and retreat to the east. The militia glared and grumbled, but the citizens of Gonzales lurched into a panicked flight, the beginning of a growing throng heading east as well, what Texians would later call the “Runaway Scrape.” Houston helped at the outset by giving up as many wagons and as much livestock as he could spare to carry civilians and their property. The gesture meant his military retreat would be low on provisions and without artillery. His men, already brooding about joining the Runaway Scrape, were outraged that their commander had two perfectly good field pieces thrown in the Guadalupe.

Before pulling out of Gonzales, Houston dispatched a courier to Col. James Fannin in Goliad with a terse message: destroy his works and immediately retire east, aiming for Victoria on the Guadalupe if he could manage it. Houston didn't hold out much hope for Fannin. He took no comfort in being confirmed in his judgment that Travis had been reckless rather than daring, and he believed Fannin only seemed steadfast because he was indecisive. In fact, Houston believed James Fannin to be a singularly unlucky man beset by misfortune as well as bad judgment. Houston would take no comfort when he was proved right about that too.

The Runaway Scrape

As the trickle of settlers from Gonzalez became a flood of refugees from neighboring settlements, they tried to stay close to Houston’s army. Throughout its retreat, it would grow when fed by optimistic rumors and shrink when shaken by grim facts. Retreat is never good for the morale of even a trained army, and in this raw one, some men lost their tempers or lost their nerve or simply lost hope. From such motives they left to fend for themselves or look after their families in the slogging eastward exodus. The news Houston received was consistently bad, but he put the best face on it for his men. Occasionally he resorted to outright lies, especially when he told them that he was looking for a place to make a stand. As the days passed without that happening, the men began to suspect he was an incompetent or a coward, perhaps both. Four days after leaving Gonzales, he reached the Colorado River and crossed at Burnham’s Ferry, which he destroyed before moving south along the Colorado’s east bank to Beason’s Crossing. He declared that the Colorado was where the retreat would end.

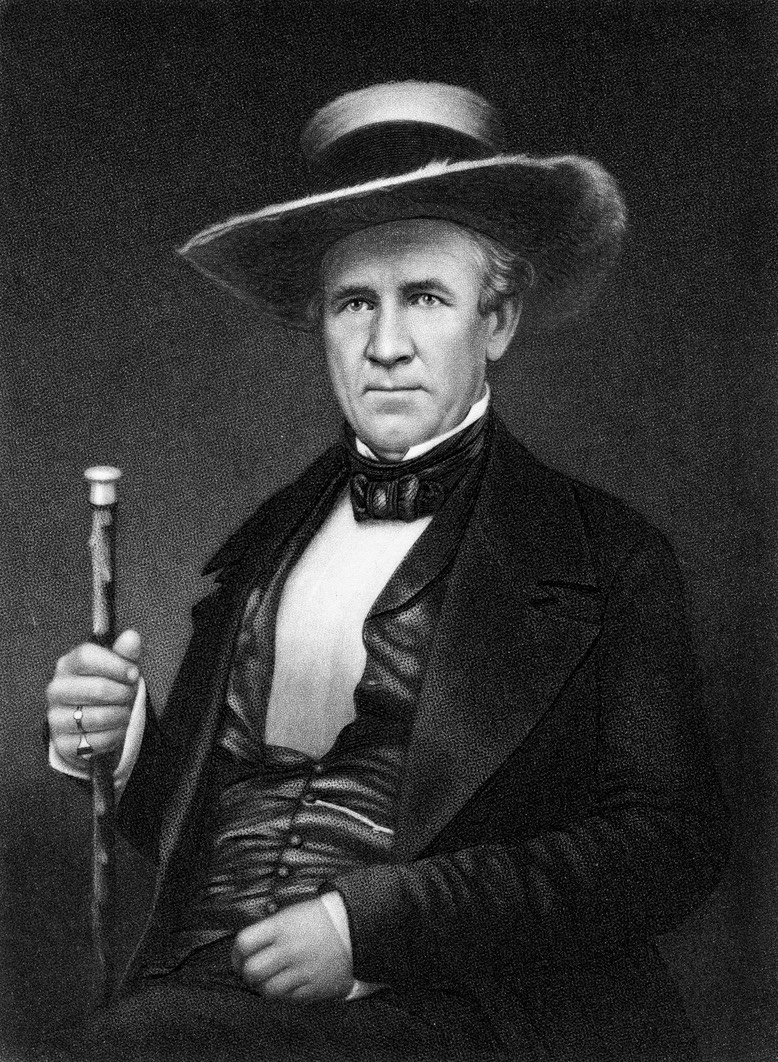

Sam Houston

Sam Houston almost certainly knew this was not true. Despite their swagger, his men would not stand a chance against Santa Anna’s disciplined and drilled soldados. They didn’t know how to march in file. They ambled down roads like an enormous amoeba, spilling this way and that, pausing for no reason, and stopping altogether when they felt like it. They were angry and brave, but that made them eager to take meaningless risks while making them more or less unruly all the time. They treated orders as suggestions and made clear their obedience was conditional and always depended on circumstances. When hungry and tired, they were surly and unmanageable, and as their respect for Houston ebbed, they openly talked about replacing him. Some of Houston’s ambitious officers encouraged the talk, some because they were impatient with the retreat, others because they were itching to take his place. The traces of treachery made Houston more taciturn than usual. He convened no councils and seldom opened his mind to his staff.

On the Colorado at Beason’s Crossing and with the promise of a fight soon to happen, Houston’s strength increased to almost 1,400 men. On March 21, scouts reported that Santa Anna’s lead divisions from Béxar were camped just across the Colorado. At this point they were about half of Houston’s strength, their march having been a straggling exercise beset by swollen rivers with swift currents, a result of incessant rain that turned bogs into marshes and bayous into swamps. For a couple of days, the Mexican encampment sat tantalizingly close to the Texians, the freshet of the Colorado separating them, one of the few times during the revolution that Texians enjoyed superior numbers. That made Houston’s reluctance to fight all the more exasperating.

Everyone was still idle on March 23 when news arrived that Fannin’s entire command had been captured, a report that so unnerved the ad interim Texian government that Burnet and his cabinet evacuated the capital and commenced running toward the Gulf Coast. Their obvious panic intensified that of the civilian population, swelling the Runaway Scrape and troubling the army. For his part, Houston finally gave up the ruse about an impending fight and ordered another retreat twenty miles farther east to the Brazos River. The move disgusted many, and they reacted to it by simply drifting away without excuse or compunction. By the time, Sam Houston reached San Felipe on the Brazos, he had lost half his army, and when he announced it would immediately head north away from the most populous settlements, a sizable portion of it bluntly refused to go. Houston discovered that two company captains were behind this first open and rank show of disobedience.

So he finally was forced to confront a serious crisis in command that could have completely disintegrated the only thing standing between Santa Anna and the whole of Texas, every inch of land for two hundred miles to the Sabine and the United States. Sam Houston knew he could not give these men an order they would not obey, so he gave them a job they could not refuse. He asked them to guard the crossings on the Brazos at San Felipe and downriver at Fort Bend. Perhaps they suspected a trick, but in the little clearing with rain pelting their buckskins and the Brazos running strong, they sullenly turned to the task. Houston marched the depleted remainder of the Army of the Republic north to the plantation owned by wealthy Jared Groce, a friend whose bounteous larder could feed the men while the remote location could keep them safe. President Burnet was livid. He mocked Houston and said the enemy was doing the same.

Houston ignored Burnet, who, having come unglued, wasn't sticking around — he and the cabinet would eventually flee to the safety of Galveston Island. Houston, on the other hand, had reason to worry about the safety of the army right then and there, for whether it was by insubordination or by defeat in battle, losing this little throng of feisty, impatient men would lose Texas, likely forever. So he chose to tuck them all away at Groce’s rather than serve them up to the Mexican armies under Santa Anna that were trudging inexorably toward East Texas, plundering towns and villages before burning them down, violating women, and exacting biblical retributions with a devil’s whip. Despite calls for mercy from his own officers, Santa Anna ordered the murder of every man in Fannin’s command. Those who managed to escape and find their way to Houston brought horrible tales of unspeakable and cold-blooded cruelty, with the promise of more to come.

Houston looked into these survivors’ haunted eyes and saw something primal. He watched his men’s reaction to the stories of point-blank executions of their friends and neighbors and gauged their resolve against the promise that they too would all be lined up and shot if Santa Anna could find them. Over the course of two weeks, with these thoughts fresh in everyone’s mind, he taught them how to march in cohesion, pivot as units, hold their fire when needed, keep quiet when necessary, trail arms before an attack, and move double-quick during one. It was hard work, but for once it passed without complaint as they were reorganized and made reasonably ready. They would have to be. From captured dispatches, Houston finally knew where Santa Anna was and how many men he had.

On April 11, the Army of the Republic cheered as two artillery pieces were brought into the camp from the coast, a gift from Cincinnati, Ohio, to the cause of liberty. The men had barely had time to dub them the “Twin Sisters” before fresh excitement raced through their ranks. They were leaving Groce’s the next day.

In mid-April, General Houston began his march toward the Harrisburg Road on which the Army of the Republic eventually reached a fork. The one on the left was the start of the 200-mile trek to the Sabine and the safety of the United States. The one on the right headed toward Buffalo Bayou, the usually lazy stream now swollen that emptied into the San Jacinto River above Lynch’s Ferry. The advance units paused only briefly before the order came. Sam Houston said in a calm voice, “Columns right.” As the men in more or less orderly files — after the training at Groce’s they no longer moved like an amoeba — as these men became aware in a wave of realization what they were doing and where they were going, they shouted themselves hoarse. Ol’ Sam was all right, after all.

So it was that the men with something primal in their eyes cheered and headed toward the San Jacinto and vengeance. They had been on the run for only about a month, but it had often seemed as if the two hundred miles back to the Alamo were two hundred years, at least until the third week of that April in 1836. Then what had happened there was again instantly and vividly memorable. They could not forget that poor blasted woman with her dumbstruck child trembling in Gonzales with the devil’s letter in hand and the stench of charred corpses at Béxar still in their nostrils. Remembing that, the men marching toward San Jacinto were ready for a reckoning. Because Ol’ Sam had saved them for the fight while teaching them how to wage it, they would meet the devil traveling under the name of Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. They would show him their version of hell.