A sketch of the Artist

as an Ageless Man

George Washington never liked him, and in the end, Martha Washington found him vexing. Yet the painter Gilbert Stuart could be charming. “Gibby” specialized in the sort of irreverence made fashionable a century later by the japes of James McNeil Whistler and Oscar Wilde. Like them, he viewed life through twinkling eyes and lived for the moment.

Wherever his moment happened to be, it was always expensive. But Stuart seldom bothered to balance his accounts. As long as he had credit, he figured he had money, and he freely spent it, as all his exasperated creditors eventually discovered. Tall and with his red hair tousled, Stuart shuffled when he walked and saw the amusing side of any situation. He brimmed with barbed comments.

“Why, Mr. Stuart,” exclaimed a woman who chattered incessantly while sitting for her portrait, “you have painted me with my mouth open!”

“Madam,” Stuart said flatly, “your mouth is always open.”

Yet Gibby also sided with anyone who was kind, and he sincerely admired talented contemporaries. The artist John Trumbull should have been a rival. Stuart made him a pal.

Gilbert Stuart’s father was a Scot who moved to Rhode Island in 1751 to set up a snuff mill, and it was there that Gilbert was born in 1755, a mere 263 years ago this month on December 3. We’re not reaching for sarcasm by using “mere” to describe something that happened more than two and a half centuries ago. An aura of modernity defined Gilbert Stuart, and he would fit right in at your holiday party this Christmas. Stuart always showed up where there was free food and drink as long as there was also the chance to be clever.

His father’s mill never made much money, and the family soon moved to Providence where his dad tried running a shop while young Stuart attended school. He showed an aptitude for drawing. Raw talent led to an apprenticeship under a wandering portrait painter with the winsome name of Cosmo Alexander, but there was nothing winsome about the hard life of the traveling artist. Cosmo and Gibby traveled the colonies and finally went abroad at which point Cosmo abruptly died. Just that quickly, Stuart was an abandoned teenager having to fend for himself.

He returned to America in 1773 and styled himself a portrait painter, but he was young, and the country was preoccupied with its arguments with Britain. His brief acquaintance with John Singleton Copley — they had something in common in that Copley’s father was a tobacconist — gave Stuart the idea of adopting Copley’s technique of placing props in portraits for drama. Copley sailed for England before the Revolution in 1774 and never returned, and Stuart followed him the following year. The troubles with Britain drove Stuart’s Loyalist family to Nova Scotia, and he judged war with Britain would make portrait painters of little consequence, so in September 1775, just months after farmers clashed with Redcoats at Lexington and Concord, Stuart boarded a ship for London.

He almost never came back. Commissions came his way thanks to well-connected friends, but he was easily distracted and was often late with his paintings. Sometimes he didn’t finish them. With debts mounting, he sought refuge with Benjamin West and was given the job of painting fill work and producing copies of West’s originals. For five years Stuart toiled away at this unrewarding and undistinguished labor, but West was teaching him things he could never have learned elsewhere or otherwise. Best of all, his connection with this kindly genius gained him entrée to prestigious exhibitions where his portraits, including a fine one of Benjamin West himself, were hanging next to work by Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough.

Gibby married Charlotte Coates in 1787, a girl he met by chance. He was attending anatomy lectures to improve his realism and struck up an acquaintance with a medical student who happened to be Charlotte’s older brother. At nineteen Charlotte was considerably younger than Stuart at thirty-one, at least chronologically, but regarding maturity, she was always the responsible one. Gibby impishly (and inexplicably) nicknamed her “Tom,” and they were happy through times both flush and lean.

They started a family right away, and Stuart moved from West’s painting rooms and tutelage and began producing portraits for the wealthiest members of London society. Regardless of his success, he always managed to spend more than he earned. Debts dogged him in England and then in Ireland, and he treated evading creditors and bailiffs like a lighthearted game, one he occasionally lost to land in debtors’ prison. More from financial necessity than an artistic impulse, Stuart hit upon a grand scheme to remove him from his creditors’ reach while supplying the means to pay them off. He would return to America, now the United States, and paint portraits of prominent Americans wealthy enough to make him flush once and for all. “There I expect to make a fortune by Washington alone,” Stuart crowed. Gibby had never laid eyes on George Washington.

He was penniless when his family boarded a ship in the spring of 1793 with Stuart paying for their passage to America by painting a portrait of the ship’s captain. In New York, no rivals could match his talent, and the work mounted, starting with paintings of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Jay, of Aaron Burr, and of Horatio Gates, the elderly patriot general who matched Stuart drink for drink during sittings. Stuart then traveled to Philadelphia to bag his main quarry, President George Washington. He had a letter of introduction from John Jay, even though Stuart had yet to deliver the commissioned portrait of the Chief Justice to the Jay family. Some things never changed.

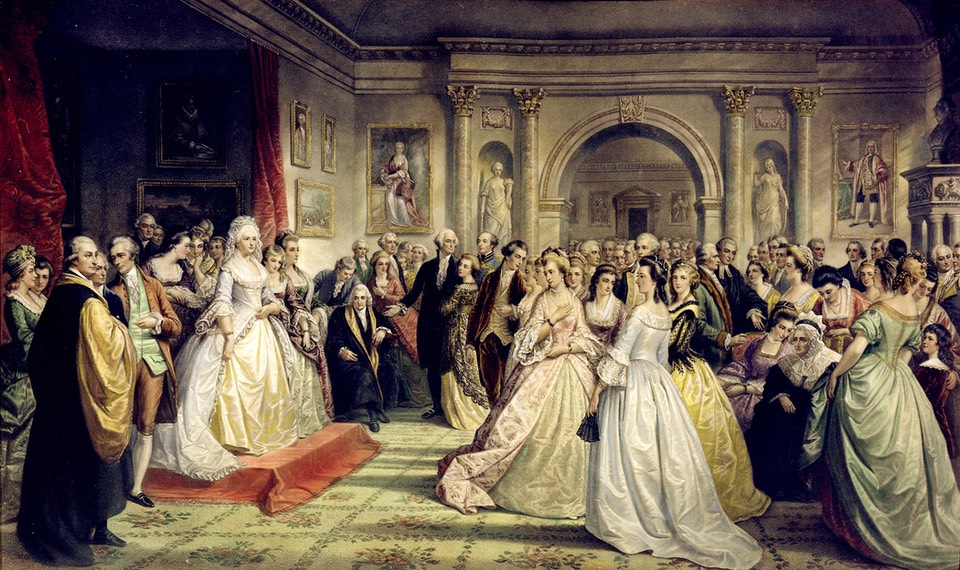

And that was true of his luck as well, which was in full force. Shortly after arriving in Philadelphia, Stuart received an invitation to visit the official residence and arrived that evening to discover the event was Martha Washington’s weekly reception. The absence of ceremony surprised him. In fact, after being ushered into the house’s main room, he stood uncomfortably alone for a time until a tall man in a black velvet suit noticed him, strode across the room, and introduced himself as George Washington. Gilbert Stuart was uncharacteristically confounded. He began jabbering until Washington gently rescued him with “easy conversation,” took his arm, and escorted him around the room.

Martha Washington’s receptions were informal affairs

The painter soon regained his composure. He persuaded the president to sit for him several times during the winter of 1794-95. Washington was sixty-three by this time with his jaw gone jowly and his mouth constantly pursed over his uncomfortable dentures. It posed a problem for Stuart, who wanted a heroic image that would become a popular seller. Besides, Washington’s kindness toward the painter didn’t last. Even though Stuart’s usually amusing banter could delight even a sour New Englander like John Adams, Washington didn’t care for it.

“Now, sir,” Stuart ventured at their first sitting, “you must let me forget that you are General Washington and that I am Stuart, the painter.”

Washington impassively responded: “Mr. Stuart need never feel the need of forgetting who he is, or who General Washington is.”

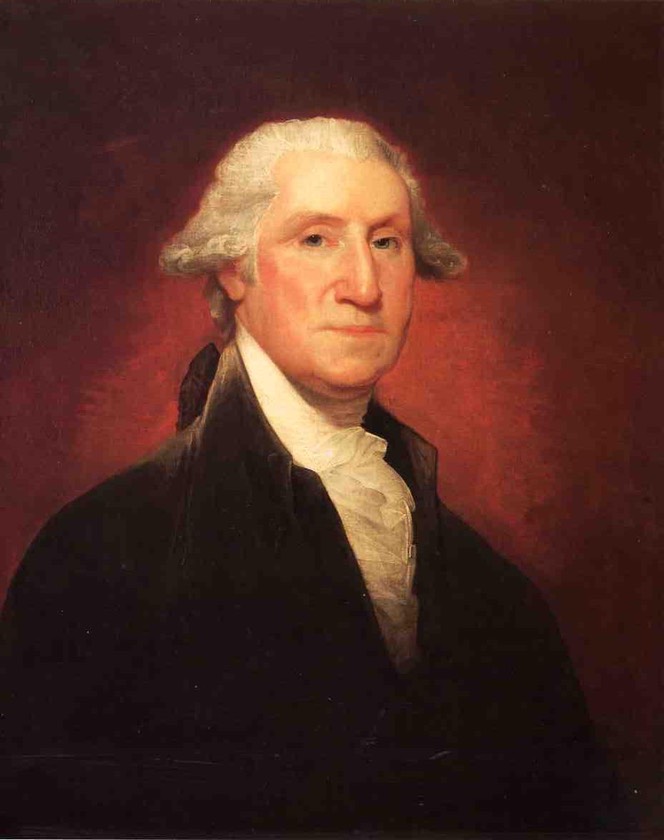

With that sort of start, it soon became clear that Stuart mildly irritated Washington, and Stuart returned the favor in the end by painting mildly irritating portraits of George Washington. At first, Washington’s face fascinated Stuart with its lionlike brow and broad-bridged nose, yet the first painting — known as the “Vaughan portrait” after Philadelphian John Vaughan who commissioned it — disappointed even Stuart. The public, however, loved it. The Vaughan portrait was not only a critical success but a stupendous financial one, especially because Stuart deliberately made it small to ease reproduction. He speedily cranked out replicas for wealthy subscribers. Stuart was overwhelmed by the demand and had to hire an assistant, a talented youngster named John Vanderlyn, to help turn the copies out.

Nevertheless, some people insisted that Stuart’s portrait did not look like George Washington. The artists in the family of Charles Willson Peale were caustic. Stuart, the Peales complained, had cast certain features too prominently and had made the complexion too flushed. They thought Washington’s nose, which Stuart made quite large, was monstrous.

The Vaughan Portrait

Because Martha wanted to have current likenesses of herself and her husband, Stuart was given another chance at capturing the president. Martha had difficulty persuading Washington to endure another sitting, for he had developed a studied dislike of Gilbert Stuart. The painter drank too much, neglected his bills, ignored both clock and calendar, and prattled on about nothing. Only because Washington, in the end, would do anything to please Martha did he submit.

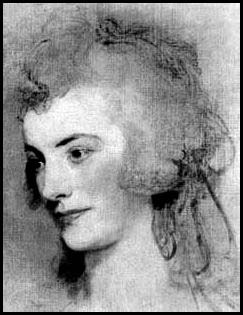

This displeasure alone would have set his mouth in a dull attitude and fogged his eyes, and Stuart toiled at keeping Washington focused during lengthy sittings. He complained that his subject never changed his expression despite the liveliest and wittiest repartee. When some horses passing outside Stuart’s studio brought a hint of a small smile to Washington’s stony face, Stuart rejoiced and took what he could get. When badinage proved useless, he suggested that Washington bring friends and family to the studio for companionship. Martha occasionally appeared, as did her grandchildren Wash and Nelly, the girl now nearing sixteen and as precocious as she was pretty. Old friends such as Henry Knox and Henry Lee also made Washington cheerful, and fetching girls always could, and they too pitched in. Harriet Chew was a particular favorite.

Anne Willing Bingham

Stuart seemed to work diligently on the portraits of Martha and the president, but wealthy William and Anne Bingham interrupted him with a job too lucrative to pass up. It was a commission to paint a Washington portrait for William Petty, Lord Lansdowne of England, and Bingham offered to pay $1,000 for it. The “Lansdowne Portrait” was finished in 1796 and was to become the most legendary painting of George Washington. At the time, however, it was a distraction because Stuart turned his full attention to completing it as a full-length portrayal. Beautiful Anne Bingham persuaded the president to sit for this special project, but the requirement of a larger-than-life painting posed several problems, especially since Stuart was never comfortable drawing people’s bodies. As it turned out, the body in the Lansdowne Portrait isn’t George Washington’s but that of a stand-in. Also, Washington’s hands are likely Gilbert Stuart’s and thus are smaller in the portrait than Washington’s were.

The Lansdowne Portrait

Nevertheless, topical urgency made haste necessary, and Stuart completed the Bingham commission quickly, laboring more diligently on it than he had on anything in years. He even made himself sick, but by late 1796 he was done. In the finished painting, Washington is dressed in black velvet and wears a ruffled shirt. His left hand holds a sheathed sword at his side, and his right arm is in mid-gesture with his palm up and fingers open pointing at nothing in particular. Although some say Washington is gesturing at the future, others insist that he is pointing to documents which could have been Jay’s Treaty. Washington’s face reflects Stuart’s economy of effort, for it’s similar to those in many of his other portraits and their copies. It seems to have been lifted directly from the picture that he had been working on for Martha Washington.

The Lansdowne Portrait is most famous because Dolley Madison rescued its replica during the War of 1812 as the British occupied the capital and later torched the Executive Mansion. But it would never be as familiar as the smaller one Martha had commissioned and was still pestering Stuart to deliver, along with the one of her, even after Washington’s death.

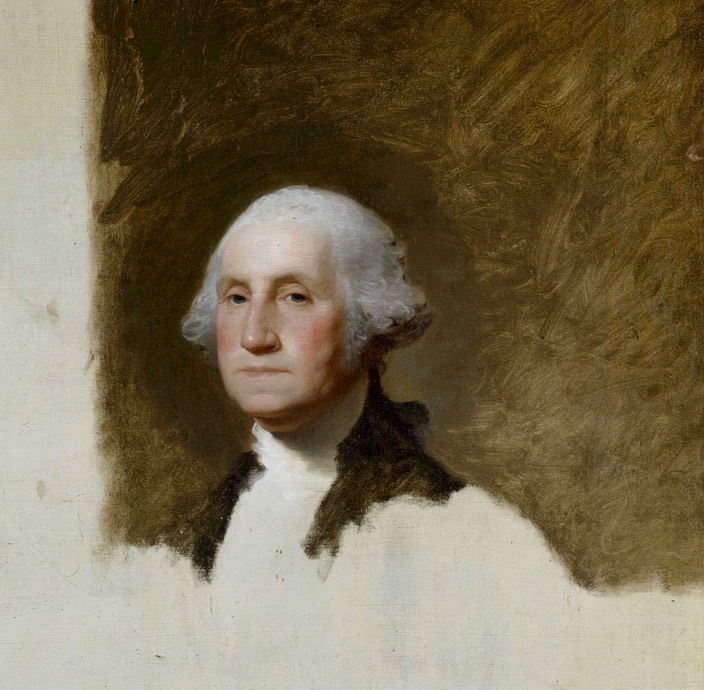

As was sometimes his way, Stuart never finished that painting. It came to be called the “Athenaeum Portrait” because the Boston Athenaeum eventually possessed it, and only Washington’s head and partially filled in shoulders occupy the canvas. Even so, it is without a doubt the most reproduced image of George Washington in all the world, fixing in memory what the first president looked like.

Gibby would have dissolved in laughter over the irony. He was the chronically impoverished artist who painted the face that ended up on the dollar bill.