They tried to suppress the disturbing feeling

that they were all going to die.

March 6 is the anniversary of the Texas Revolution’s defining moment 184 years ago. The course of events that culminated with the fall of the Alamo provides an excellent example of courage in the face of certain death and not the kind of certain death that springs upon unaware men to surprise them with a brief flash of terror before turning the lights out. Instead, it was the kind of certain death that slowly tortures with the hopelessness of days relentlessly passing toward an inevitable, ugly end. Some people go mad when confronting a thing like that. The men at the Alamo clenched their jaws and waited. When the time came, they fought.

All the unpleasantness had started the previous year when Americans living in Mexico’s northern province openly defied Mexico City’s authority. They were objecting to the dictatorial methods of President Antonio López de Santa Anna. A mixture of charm and egotism made Santa Anna charismatic, but he was corrupt in his governance and careless with the truth. He also had developed habits of cruelty as a form of recreation. He sometimes sustained his will with a brutality that could disgust even his admirers.

Antonio López de Santa Anna

When Texans pushed back in the summer of 1835, and Santa Anna began quelling unrest with military force, the province revolted. By October, there was gunplay and no turning back. That December, a gaggle of gentlemen farmers in tailored waistcoats and frontiersmen in buckskins overran the Mexican garrison in San Antonio de Bexar and unknowingly set the stage for one of the most profound events in American history.

Texan defiance outraged Santa Anna. By late January 1836, he had raised an army of 4,000 soldiers to enter Texas from Saltillo. Other Mexican forces were also assembling. Abysmal weather and lousy provisions discouraged Santa Anna’s army as it moved toward San Antonio in February, and their numbers dwindled to about 2,500. It was still more than enough.

Many who had taken San Antonio in December would not be there when Santa Anna arrived. They were in Texas seeking easy fortunes, and the prospect of risking their lives fighting a Mexican army promised to be neither painless nor profitable. Many ran away, stealing what they could carry as they did so, and the rest were mostly mercenaries who planned to pillage the Mexican city of Matamoros several hundred miles away. That caper was going to pull much-needed men and supplies away from already vulnerable points, including San Antonio.

Even worse were the disputes that developed over command of Texas troops. A hastily assembled citizens’ council tried to organize a territorial defense by naming Sam Houston as the overall commander, but it then distributed authority among several others as well. The result was chaos. When Governor Henry Smith tried to bring order to the situation, the council attempted to remove him from office. As this confusion and petty bickering continued, Santa Anna and his armies continued their remorseless march north.

James Bowie

In early 1836, Texas military forces consisted of three small, ill-supplied, disorganized bodies of soldiers. One was a small group at Goliad under the command of James Fannin, and another was composed of the mercenaries heading for Matamoros. The third was the 100-man garrison at San Antonio under the command of Col. James C. Neill who had set up headquarters at a former Catholic mission called the Alamo. In mid-January, Houston sent a small detachment under Kentucky native and Louisiana transplant James “Jim” Bowie to the Alamo, apparently with orders that if Bowie deemed the fort indefensible, he was to destroy it and pull everybody northward. Exercising judgment that can only be described as immensely significant, Bowie not only decided the post was sound, he resolved to help defend it. He immediately sent out calls for reinforcements.

David Crockett

Tennessean David Crockett (only legend and Walt Disney had him as “Davy”) was one of the adventurers whose arrival with a small band of companions boosted the small garrison’s morale. Crockett had traveled all the way from the United States to participate in the Texas Revolution, while others came from closer locales. Crockett held no command at the Alamo, but he was the kind of man other men heeded.

Alabama transplant William Barret Travis had been variously a lawyer and a smuggler but was now a lieutenant colonel in the Texas regular army, and he brought thirty additional men to the Alamo. This made the Alamo’s less than 150 men a scant handful gathered in the path of approaching thousands.

Short of men, the Alamo nevertheless boasted an awkward abundance of commanders. When a family emergency called away Neill in mid-February, Bowie the volunteer and Travis the regular began to butt heads. Both had more than a measure of pride and vanity, and only with difficulty did they arrange a compromise to share command. The cumbersome arrangement was never tested. Bowie became so ill with typhoid that Travis exercised sole command during the ensuing events. He was 26-years-old.

William B. Travis

Santa Anna and his army occupied San Antonio and laid siege to the Alamo in February. He hoisted a red flag on the town’s church to announce that no mercy would be shown to rebels. While he still could, Travis continued to call for reinforcements, and the men in the little mission held out hope that help was on its way. After all, the 200 men at Goliad must have heard of the Alamo’s predicament. James Fannin had decided to hold his position, though, and Santa Anna’s patrolling cavalry soon made Fannin’s decision binding.

In the thirteen days that remained to them, the men in the Alamo shored up their makeshift fort while trying to suppress the disturbing feeling that they were all going to die. Even when 32 new men trudged into the Alamo from Gonzalez, the odds were impossible to ignore. The Gonzalez contingent would be the last to join Travis’s doomed command as Santa Anna’s cavalry tightened its grip. The men from Gonzalez weighed the odds in an instant. They chose to ignore them.

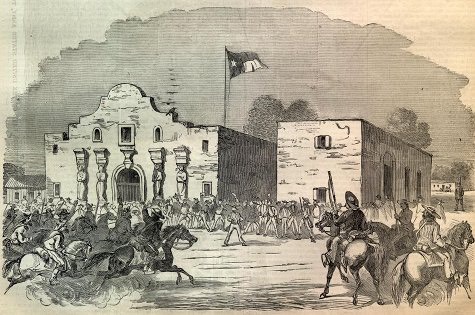

March 6, 1836

Almost constant bombardment from Santa Anna’s artillery battered the Alamo’s walls. It was only a matter of time before the Mexicans mounted an irresistible assault, and when it came at last on March 6, the men in the Alamo never had a chance. Before dawn, Mexican soldiers crept close to the fort and attacked at several different points before the Texans could sound an alarm.

They put up a stout defense, though, desperately fighting in small pockets that were quickly isolated by the overwhelming number of attackers. Travis fell dead early, but it hardly mattered in terms of command. Everyone’s fate had been sealed weeks before when Santa Anna had first appeared from the south. Fighting became especially vicious as the Mexicans swamped the Texans in hand-to-hand combat. At the end, when all was lost, fewer than ten of the Alamo’s garrison were said to have surrendered. The assault had cost Santa Anna some 600 soldiers dead and wounded before it was done, before all of the defenders were dead.

Santa Anna had the few male prisoners executed. All the corpses from the Alamo were piled up and set on fire. Santa Anna spared one woman and her baby and Travis’s slave Joe. He did it less from compassion than to have them bear witness to revolutionaries elsewhere of what they had seen. This fate awaited the Texan rabble, Santa Anna decreed.

Thus did news of the Alamo spread. Flush with this “victory,” Santa Anna was sure that his ferocity would terrify Texas into submission.

He had no idea of the reckoning that it would instead summon. The place became a rallying cry, and the men in it became more than martyrs to a cause. They became an enduring inspiration to people everywhere who challenge enormous power armed with countless numbers. Steely courage that counts no costs in fighting irresistible power cannot be extinguished. At the Alamo, Santa Anna killed every one of those men. To the end of his days, he never understood why not one of them would ever die.