There was something like the aroma of earth about her

Her family was of good stock, her father one of the founders of the little settlement on the Cumberland River named Nashville. That fact alone made her family prominent in the community, but Rachel Donelson’s life was etched by the frontier. She spoke with the thick twang of the backwoods and in a vocabulary rich with regionalisms that would have struck eastern ears as unrefined, even uncouth, especially when she regularly mixed up subjects and verbs. She liked tobacco, later preferred a pipe to smoke it, and never learned her letters beyond the rudiments. The infrequent correspondence she scrawled over the years gives the impression of her gripping a pencil while biting her tongue.

She was a spirited girl, though, pretty and pleasant and acquainted with the toll of the wilderness. When she was 18 someone — Indians or white robbers, depending on who one asked — killed her father, leaving her mother a forlorn widow in a remote blockhouse and in need of protectors. The widow Donelson took in boarders.

The first was a bookish lawyer named John Overton, a Virginia transplant by way of Kentucky, whose owl-like eyes made him seem older than his 23 years, but whose soft voice and slight frame didn’t promise much in the way of protection. The situation improved when a gangly redhead with a long face and commanding presence came along. Andy Jackson wasn’t built much better than Overton, but his height and carriage made him seem formidable, and his pockmarked face with the strange welt on his brow suggested a man who had seen something of life, though he was barely past twenty. He and Overton hit it off immediately, which made the household pleasant.

It was the girl, however, who made it glow, even though she wasn't supposed to be there. By the time Overton and Jackson showed up in Nashville, Rachel Donelson was married to a dashing Kentuckian name Lewis Robards and had been living far away from her girlhood home. Possibly it had started as a love match. Rachel was fetching, and Robards came from a good Virginia family that pronounced its name "Roberts" and had the habit of marrying well. But even if loveless and arranged, the union seemed likely to be prosperous if not palatable.

In this portrait, Rachel Jackson was entering middle age as a handsome woman who retained more than a hint of the girl who had turned men’s heads. She had stunned Andrew Jackson when they were both barely out of their teens.

Sadly, it became neither quickly. Robards was proud of his wife, but he bristled when other men noticed why. Soon he was flying into jealous rages if Rachel traded a routine pleasantry with anyone male over fifteen and under fifty. He was verbally abusive and, encouraged by strong drink, he could use an open hand to drive home his point. It all drove Rachel Robards to go home to her mother. She was there when the solemn Overton arrived, and so she was there when the tall, blue-eyed stranger from North Carolina came looking for bed and board.

Both of the young men were captivated from the beginning. Overton was bashful by nature, and Rachel possibly flirted a bit even though married — after all, she was unhappily married. For whatever reason, Overton tended to be wistful when she took up a bucket to carry water or pushed her hair away from her face when sweating over a chore. Rachel moved with a natural grace, smiles coming naturally to her and something like the aroma of earth about her.

It was the sort of thing that made men pause to stare and stammer — the very thing that made Lewis Robards crazy with jealousy.

Rachel liked John Overton, but she fell in love with Andrew Jackson, most likely within days of meeting him. There was probably flirtation in play, but there did not need to be. Andrew Jackson was enchanted the moment he laid eyes on Rachel Robards. It soon became plain that the two were more than friends. When Robards showed up to reconcile with his wife, he found a young woman changed and distant. He was accustomed to imagining her supposed assignations with other men, and even if she and Jackson had been on their most reticent behavior, it would not have mattered. Lewis Robards suspected the worst, threw one of his tantrums, and decamped for Kentucky.

Later, speculation had Jackson, after this episode, intent on shielding Rachel from her abusive husband by taking her to Natchez in the summer of 1791. The place was at some remove from Nashville; it was in Spanish territory, and Jackson had business interests there ranging from slave-trading to land speculation. Such activities had required him to swear allegiance to the king of Spain, which was unappealing but had the advantage of giving him access to Spanish legal authority. According to the stories, he was ready to use that access as soon as he heard that Robards had divorced Rachel. By then, Jackson had left her with friends in Natchez and returned to Nashville, but he raced back with the glad tidings and, it was said, married Rachel under Spanish law.

It is unlikely that any of this happened in this way. No document records a marriage in Natchez, but there is one that indicates the two were living as man and wife as early as January 1791, months before they presumably traveled there and months before Jackson could have heard that Lewis Robards had obtained a divorce. In short, the Natchez marriage is almost surely a fiction, but none of their neighbors cared that they were not formally married.

On a frontier where the wilderness could swallow up a spouse without a trace, marriage as a state of mind was not that rare, and it could carry as much weight as officially sanctioned matrimony. If anyone chuckled over the Jacksons, it would have been with good-natured references to rising sap and buzzing bees, and it would have been kept quiet in any case. Everyone knew about the husband's reaction to jokes of a particular type. Moreover, nobody would want to wound the smiling girl they liked and were glad to see at last happy.

Two uneventful years later, though, the fact that they were not married suddenly became a problem, and the scandal of their situation forever scarred her heart and set him to cocking his ear for gossip and cocking his pistols to stop it. John Overton brought them unsettling news. Lewis Robards had only petitioned the Virginia legislature (then with jurisdiction over Kentucky) for permission to seek a divorce. He had not obtained a final decree dissolving the marriage. At the time, people in the region were eager to shed their backwoods past and enter more fashionable society, and their previous indifference to Jackson’s and Rachel’s quasi-marriage disappeared. It was in this atmosphere that Andrew and Rachel not only discovered they were not legally married, but that Rachel was legally a bigamist with the sin of adultery thrown in for shameful measure.

Overton also reported that Robards had finally obtained his divorce. It was on his advice that his friends quietly married in the traditional way of listening to a parson tell them what they already knew about sickness, health, and putting things asunder. But that was not the end of it, as the circumstances of her divorce were humiliating. For the rest of her life, at stray moments, Rachel’s eyes could become sad and haunted. Over the years, she buried herself in her Bible for solace, puzzling out the words with fierce resolve, becoming pious as she became portly.

Andrew Jackson loved her more than life and never minded the rough grammar, the rounding figure, nor even the pipe. He cherished the simple niceness of a good person who was devoted to him with the same fierce resolve she gave to her devotionals. She would have been joyous to live the rest of her days on the Cumberland River. She was a pious woman and a private person who loved her family and made their home a sanctuary. In the refuge that Rachel made for them all, the Jacksons had a glorious marriage. Childless themselves, they filled their lives with nieces and nephews, took in the orphaned children of friends, and even adopted one of Rachel’s nephews who became Andrew Jackson, Jr.

But for this good woman happiness was to be a fragile thread. It is unlikely that Rachel knew Shakespeare's dictum about Caesar's wife and suspicion, but it was her curse that she was fated to learn it. She never wanted her husband to be a public figure, much less President of the United States, but Jackson became famous after beating the British at New Orleans, and his quest for the presidency in 1824 and 1828 led to scrutiny and renewed gossip about their marriage. At first, the talk was veiled and infrequent, but when she visited Washington when Jackson was serving in the Senate, she had to realize that sidelong stares and whispers meant something unpleasant about her clothes, her grammar, her looks — her past.

The chatter was petty at best and thoughtlessly cruel at worst. One wag, for example, called Rachel “her majesty of two husbands.” When she came to the Capitol one afternoon to see where her husband worked, she strained to dress fashionably to make him as proud of her as she was of him. Delaware representative Louis McLane saw only “an ordinary looking old woman dressed in the height & flame of fashion," which did not so much describe Rachel Jackson as reveal McLane’s ability to abandon any pretense of gallantry with piffling criticisms of a kind lady's appearance, age, and attire. But McLane was hardly done. No one, he said, would "be able to make her fashionable, and if she presides in the palace, her reign will be any thing but glorious." After all, he solemnly pronounced, once a woman "loses the high charm of immaculate chastity, . . . tears & repentance are her lot, and her fit occupation, constant devotion to make attonement [sic] for the injury to publick morals."

When Jackson failed to win the presidency in 1824, his campaign for the 1828 election began immediately. In one of the dirtiest presidential contests in American political history, Rachel Jackson became a tragic victim.

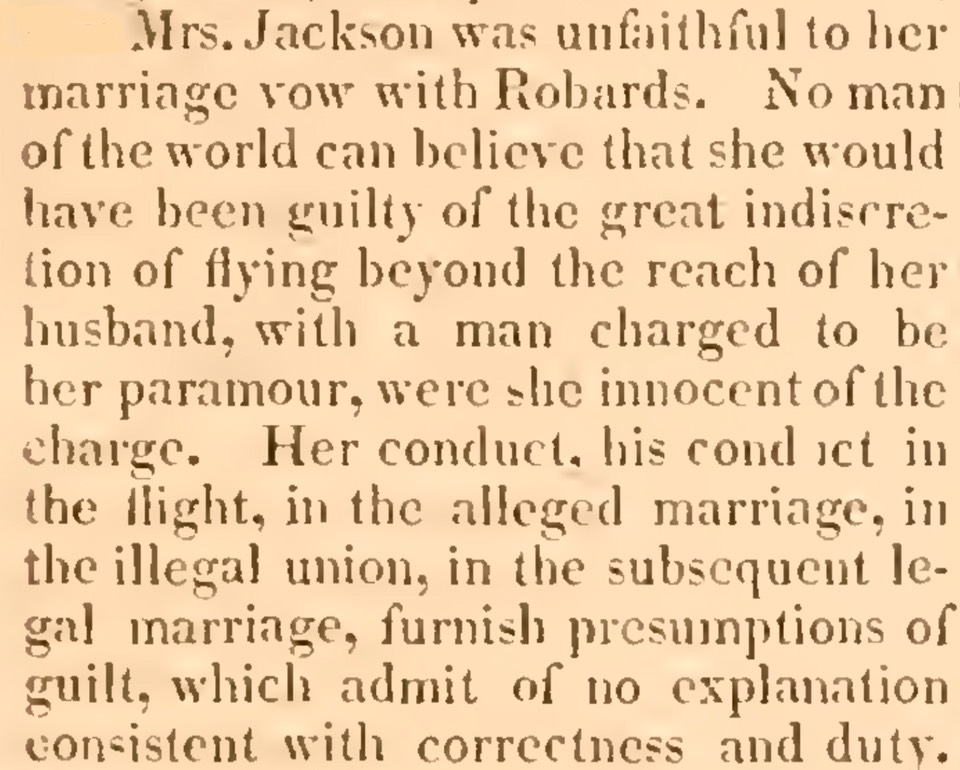

A typical attack on the Jackson marriage during the 1828 campaign

Jackson’s enemies described her as an adulterous bigamist, a woman who had never led a virtuous life either before or after her two marriages, an “American Jezebel.” Rachel preserved a calm dignity throughout the ordeal, but nobody could shield her from the stories. She had known as much from the moment all those years before when the news about the divorce that had not happened began to shadow her world. “The Enemyes of the Genls,” she told a friend in a lament hued by her Bible, “hav Dipt their arrows in wormwood & gall & sped them at me.”

When Andrew Jackson won the election of 1828, everyone around him was ecstatic, but Rachel dreaded the prospect of going to Washington. The thought of sidelong glances from fashionable ladies whispering about her behind their fans and not altogether behind her back made it hard for her to catch her breath. She begged everyone to let her remain in Tennessee. She had nothing fashionable to wear, she claimed. She promised to join her husband in Washington later, after all of the inaugural festivities. No one would hear of it, least of all Andrew Jackson.

After all and despite the years, for him, she was youth, the sunshine on the Cumberland River, the girl with the smile that could make songbirds sound like silver and starlight seem golden. So many years before, he had leaned against the door jamb of the widow Donelson’s blockhouse and watched her, the “sprightly young woman,” go to the well, swinging a bucket at her side, leaving in her wake an intoxicating perfume that carried the slight fragrance of earth. He could not live without her.

But he would have to. In the end, an authority even more imposing than Andrew Jackson thought it was time that Rachel Jackson should have everything she wanted.

— This post was adapted from The Rise of Andrew Jackson: Myth, Manipulation, and the Making of Modern Politics in which Rachel’s story and others are told as part of Andrew Jackson’s quest for the presidency