This week we recall events from an eventful summer when James Monroe and Company found themselves in a great deal of trouble, and not of their own making, which is the most exasperating kind. To tell this tale we’ve adapted excerpts from our book Old Hickory’s War: Andrew Jackson and the Quest for Empire and another, The Rise of Andrew Jackson: Myth, Manipulation, and the Making of Modern Politics, coming this October and available for pre-order from fine booksellers everywhere. Also, we want to remind everybody that An American Album has been revived as a quarterly. You can sign up for it (and more) here.

__________________________

The news came as rumors during that spring and summer two hundred years ago, which made it more disquieting. Sensational tidbits dribbled into Washington piecemeal about something most irregular down South in the dense mangroves of Spanish Florida. Talk of hangings and firing squads raised eyebrows and set tongues wagging, but whispers about war detonated explosive rages in Spain’s minister to the United States. He was a doughty character named Don Luis de Onís, and he wanted answers. The United States government didn't even know the questions.

Summer was the sleepy time of year in Washington when the town’s soggy heat chased away almost all functionaries from their desks and boarding houses. The men directing the affairs of President James Monroe’s administration could be thankful at least for that. It meant that Congress was out of session, out of town, and unable to pose awkward questions. European diplomatic representatives, however, were very much present in the capital, particularly those from London and Madrid. The United States had just concluded a messy war with Great Britain, and London’s man Charles Bagot was mopping up particulars in its aftermath. For his part, Onís was in negotiations, apparently endlessly, with Secretary of State John Quincy Adams over the question, as it happened, of selling Florida to the United States. As rumors dribbled in about another messy war, this one with Spain, Onís was keen on getting some answers. Adams was rather keen on getting some answers too.

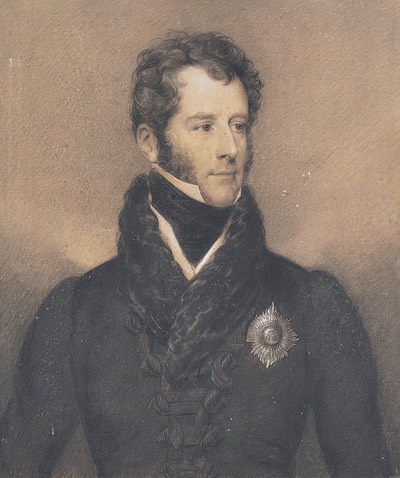

Onís

This much he knew. Months before, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun was coping with a Florida border in full turmoil. Marauding American settlers had provoked retaliation by Seminole Indians and Red Stick Creeks. The commanding general of the US Army’s Southern Department, none other than Major General Andrew Jackson, had insisted the situation required an increased military presence, but more soldiers had angered rather than awed the Indians. One thing led to another until there was a horrific incident: Indians ambushed army supply boats carrying sick civilians as well as soldiers on the Apalachicola River. The Indians killed everyone, including children, except for one woman they carried off.

Jackson wanted to retaliate with severity, and Calhoun in Washington did too, though both he and President Monroe were anxious about the potential scope and likely consequences of a military campaign. So in December 1817, Calhoun took considerable care when he drafted orders authorizing one. He limited the latitude of the American army that was to cross the Spanish border into Florida. The rationale for the incursion was what came to be called the right of “hot pursuit,” long an accepted element of international law. But Calhoun also explicitly ordered that Spanish towns and military garrisons were to be left alone. Monroe and Calhoun then made a fateful decision. They judged the situation grave enough to warrant division command, which meant Andrew Jackson would take personal command of the expedition. The idea was to punish Seminoles and Red Sticks with such vigor as to end depredations once and for all, and Jackson seemed just the man for that job.

Major General Andrew Jackson

Under these orders, Jackson mounted his campaign in March 1818, but it wasn't until early May that Monroe and his cabinet had their first inkling about Jackson’s activities in Florida. The news set everyone on edge. Jackson, it was rumored, had forced the surrender of a Spanish garrison at Saint Marks in West Florida. In other words, if the reports were accurate, Jackson had done exactly what his government had told him not to do.

Bagot

After this first troubling news, information was sparse until mid-June when a new set of rumors told of Jackson executing two British subjects. British minister Charles Bagot’s ears perked up. This seemed quite extraordinary, Bagot briskly told Adams. Adams could barely hide the fact that he agreed. In fact, the news caused Adams to furrow his brow and to cock his head in bewilderment. Assailing Spaniards in Saint Marks would be bad enough, but what on earth was Andrew Jackson doing killing Britons in the Florida wilderness?

But the bad news soon got worse. Rumors beyond those about the murders were just chilling. Jackson, it was said, had marched on the provincial capital of Spanish West Florida, had taken it as a prize of war, and had raised the American flag over the town as a marker of possession. This information caused Adams to sit bolt upright. He sent a terse message to President Monroe who was on an inspection tour of Chesapeake Bay fortifications. Monroe abruptly ended his tour and returned to Washington.

James Monroe

Adams came away from their meeting wide-eyed and fazed. Like everything about this developing crisis, his conversation with the president was disquieting, for in it James Monroe had displayed the side of him that even his friends found maddening. It was a sort of dim-witted talent for grasping the obvious. If the news from Florida was accurate, Monroe had solemnly mused, Jackson had undoubtedly disobeyed his orders. After this penetrating observation, the president left for his farm in Virginia. But he also left his secretary of state holding the bag. Adams wasn't even sure what might be in it.

The president had the excuse of lacking information to cover the appearance that he was running away, but impressions were hard to explain in any case. James Monroe had not always been this way, and nobody has ever been able to determine why he had, by his sixtieth year, become indecisive, tentative, even irresolute. He had become the polar opposite of himself as a youth, nothing like the kid who at eighteen had abruptly dropped out of the College of William and Mary to fight in the Revolutionary War. He was a headstrong soldier with little caution about his person and less care about his life. At the Battle of Trenton on Christmas Day of 1776, a bullet nearly killed him, but a grueling convalescence didn't dim his ardor or blunt his courage. He was the same after the war when he stood on principle so courageously that he publicly alienated important people, George Washington among them. Young Monroe was brash enough to seem foolhardy, remarkably indifferent to the way tilting at windmills damaged his otherwise promising career.

President Thomas Jefferson liked Monroe — he had taught him law after the war — and he sent Monroe to France to purchase Louisiana from Napoleon and to Britain to protect American interests amid growing tensions. And yet, Monroe imprudently challenged James Madison for the presidency in 1808, even though Madison was Jefferson’s hand-picked successor. In the aftermath of that misstep, Monroe was barely able to rehabilitate himself in the eyes of his mentors, who were inclined to judge him an ingrate. Perhaps the strenuous effort to dispel that impression was the reason Monroe gradually, imperceptibly, but no less clearly, began to recede into the safety of the unspoken thought and the seeming serenity of dull blue eyes. The angry young man became the cautious older one as he served loyally in Madison’s cabinet and did his part to keep the country from losing the War of 1812. After that war, and with the weight of the presidency on James Monroe, caution became a byword as Quixote’s once romantic windmills loomed like real dragons, all of them best avoided.

As dragons went, Andrew Jackson down in Florida was the genuine article. The incomplete news about fight and fire from that dragon sent James Monroe home to his farm. Meanwhile, Jackson’s long-awaited report about his campaign did not reach Washington for quite some time that summer, but its tardiness was the least of the many issues surrounding this affair. When a dusty courier finally dragged into Washington with the papers describing what had actually happened in March and April, the hard facts left everyone rattled.

Andrew Jackson had not merely exceeded his instructions; he had violated them in every particular with remarkable enthusiasm. His invasion of Spanish West Florida was clearly designed to seize it. In doing so, he outraged international opinion and violated the United States Constitution, which gives Congress the exclusive authority to declare war. These two transgressions were stunning offenses. One offended diplomatic sensibilities. The other broke the fundamental domestic law.

These official dispatches from Jackson, which began arriving in early July, shattered Monroe’s excuse for his absence, and he came back to Washington. The cabinet pored over what documents it had — including the December 1817 orders Calhoun had drafted about leaving Spaniards alone — and started mulling the administration’s options. The process could not have comforted the president. His secretaries either offered virtuous advice that was politically perilous or pragmatic counsel that was distasteful to consider. Worse, the cabinet could not come to an agreement. Calhoun’s was the moral point of view. He fumed that the taking of Fort St. Marks and Pensacola made apparent Jackson’s wanton disregard for executive authority and congressional prerogative.

President Monroe found it all very unsettling. Unconstitutional antics in West Florida could not be ignored, but Jackson’s enormous popularity as the Hero of New Orleans muddled Monroe more. No matter how much Old Hickory deserved it, an official reprimand of a man like that was to throw rocks at a hornets’ nest. One bright opening emerging in the discussions, however, finally lit up the president’s dull blue eyes. John Quincy Adams was just as voluble as Calhoun, but on the other side, and Monroe breathed easier listening to his secretary of state talk sense by mapping a way out of the mess.

John Quincy Adams

The peppery New Englander had been trying to buy Florida from Spain for months and despised the pointless meetings with Spanish minister Don Luis de Onís, a wily negotiator who haggled sensibly one minute only to talk jabberwocky the next. In clipped phrases and likely with his finger tapping the table to emphasize his precisely enunciated words, Adams bluntly said that chastising Jackson would achieve only two ends, both of them bad. It would enrage the public and stiffen Spain’s resolve to keep Florida. Monroe listened to Adams talk sense and later told Thomas Jefferson what they were all forlornly thinking. Punishing Jackson would “be the triumph of Spain, & confirm her in the disposition not to cede Florida.”

The Monroe administration thus decided to do what the president had discovered was best in almost all instances. It would do nothing. It would neither condone nor condemn Jackson’s campaign, and it would most assuredly not discipline Jackson himself. Calhoun was not happy, and both he and the president tried gentle persuasion to save some of the executive’s dignity. Would Jackson at least say that he had misunderstood his orders? The response was an unequivocal no. And as if to put an exclamation mark on it, Jackson began preparing troops to march on Saint Augustine, the capital of Spanish East Florida. Calhoun did not waste a second pondering that news when it trickled into Washington. He sent a direct order to Jackson forbidding any such campaign and tersely informing him that the United States intended to restore West Florida to Spain. Enough, thought Calhoun, was enough.

John Quincy Adams thought so too by this point. He had his hands full explaining to Onís why Jackson was right (hot pursuit) and how Spain was wrong (failing to control the Indians) while highlighting American magnanimity in returning a pacified province — but, Adams added for good measure, only after Spain could demonstrate its ability to keep it that way.

Luck seemed on the secretary’s side. After Onís had registered the obligatory protests, he appeared more tractable about selling Florida. Adams’s luck held when it became clear that Britain would disregard the public’s anger over two subjects of the Crown being summarily dispatched. London was wearied from fighting Napoleon Bonaparte and tired of quarreling with Americans. His Majesty’s government would not renew troubles over the fate of two adventurers who had been in Spanish Florida while Andrew Jackson was prowling around — the proverbial case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Fortune smiled on James Monroe (and Andrew Jackson, for that matter) in averting a diplomatic catastrophe. Monroe was also lucky that Congress did not convene until December, for the domestic consequences over the affair in Florida were potentially as severe as the diplomatic ones had been. The Monroe presidency stood every chance of being ruined by that, and in retrospect, it’s easy to see why a kind of paralysis set in under the shadow of the possibility. John Quincy Adams was one of the most principled men in public life, but Jackson was also the most popular of his time, and Adams was practical in gauging there to be little advantage in throwing rocks at a hornet’s nest. It was a good excuse for doing nothing.

It certainly sounded like sound advice to the man at the head of the table during the frantic discussions that summer two centuries ago. Once upon a time he had been an impetuous lad with more pluck than prudence, but Monroe by the summer of 1818 was an aging man whose finely calibrated method of deliberation had become a mask for inertia. He always preserved plenty of opportunity for disclaimer and denial and as president perfected the art of being forcefully timid, of moving with indecisive decisiveness, of feeling strongly both ways, of formulating a passively aggressive policy that threw the dice while buying time.

So Monroe placed a wavering hand firmly on the helm as he and his cabinet waited anxiously for December and the gathering of Congress. Doing nothing provided a kind of comfort. It was what Thomas Jefferson, with a happier facility for rhetorical rationalization, had called awaiting the chapter of accidents. With his finely calibrated method of deliberation, James Monroe didn't see the need to call it anything all.