He had a telescope

and too much time on his hands

Other than students of eccentricity, nobody remembers John Cleves Symmes, Jr. In the 1820s, however, he achieved a fair amount of fame because of an idea he wouldn’t let go, even when it evoked first incredulous laughter and then derision. Symmes was a humorless sobersides if there ever was one, and he was doomed to suffer the cruelest fate for someone of that temperament. He became a joke.

He was born in New Jersey to a fine family of New England stock who claimed their ancestors had been on the ship that brought Ann Hutchinson to America in 1634. Indeed, Symmes descendants were politically connected and suitably prominent. John was his uncle’s namesake, a man who was a force in colonial and early national affairs, a patriot of the Revolution, related by marriage to John Jay, and the husband of a Livingston whose daughter married William Henry Harrison. The elder Symmes also headed west to become a territorial judge and a land speculator.

With a pedigree like that, John Cleves Symmes had a leg up on a successful life. His uncle helped him receive a commission in the United States Army, but John himself was responsible for distinguished conduct during the War of 1812 when he participated in sorties during the Lake Erie campaign and fought in the Battle of Lundy’s Lane.

The peacetime military was a slow crawl of never-ending toil, though, and after the war, he retired from the army and tried his hand as a contractor provisioning army posts on the frontier. He made the painful discovery that being an honest contractor didn’t pay. His business failure consigned his family to genteel poverty.

Everybody liked John Symmes, and some people even admired him for his admirable fidelity, honesty, and sincerity. That was why in 1818 his behavior was so bewildering. On April 10 of that year, he sent a curious announcement to every newspaper he could reach under the heading of the “NO. I: CIRCULAR.”

After the quotation: “Light gives light to light discover — ad infinitum,” he announced:

“To all the World: I declare the earth is hollow and habitable within; containing a number of solid concentric spheres, one within the other, and that it is open at the poles twelve or sixteen degrees. I pledge my life in support of this truth, and am ready to explore the hollow, if the world will support and aid me in the undertaking. Jno. Cleve Symmes, Of Ohio, late Captain of Infantry.”

Symmes wasn’t entirely done, though. He added: “I have ready for the press a treatise on the ‘Principles of Matter,’ wherein I show proofs of the above positions, account for various phenomena, and disclose Dr. Darwin’s ‘Golden Secret.’My terms are the patronage of THIS and the NEW WORLDS.”

And incredibly, there was more:

“I dedicate to my wife and her ten children. I select Dr. S. L. Mitchill, Sir H. Davy, and Baron Alexander von Humboldt as my protectors. I ask one hundred brave companions, well equipped, to start from Siberia, in the fall season, with reindeer and sleighs, on the ice of the frozen sea; I engage we find a warm and rich land, stocked with thrifty vegetables and animals, if not men, on reaching one degree northward of latitude 82°; we will return in the succeeding Spring. J. C. S.”

Symmes was 38 when he published this remarkable announcement and call to action, which seems to have been prompted by the fact that he had a telescope and too much time on his hands. Saturn’s rings, Jupiter’s colored belts, sunspots, craters on the moon, and canals on Mars got him to thinking, and then he did a little reading.

Animal behavior was most instructive, he thought, especially migrations in the Arctic. Large schools of fish appeared in southern waters, and reindeer herds came south in the spring, retracing their steps in autumn. The only thing that could explain this counterintuitive activity was that they were denizens of an inner world, their enormous size indicating that it was more hospitable than the surface of our outer one.

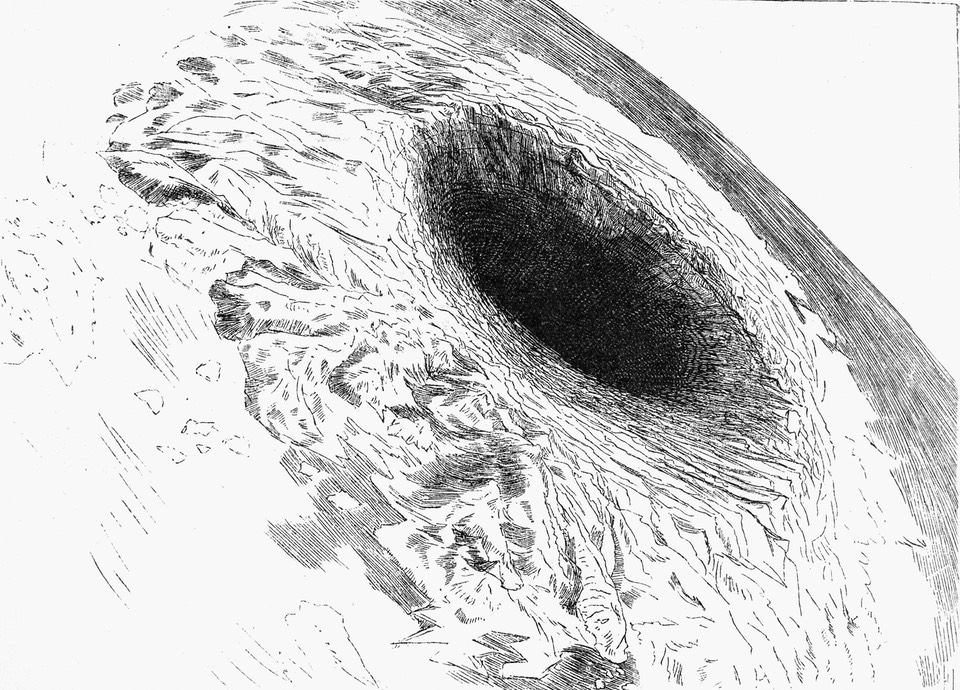

The world, according to Symmes

He not only sent his circular to newspapers but also to a long list of distinguished scientists worldwide. The postage alone consumed a lot of the family budget, and his wife Mary’s supportive indulgence had to mask her concern. Symmes assured the family that all would be well when a wealthy patron stepped up to fund an expedition that would discover and explore the polar holes.

It would require at least two ships, he ventured, and of course, he would lead the whole shebang. The world would gasp when he returned with flora and fauna from the inner world.

The handful of newspapers that published his circular did so in jest, often with some snide remarks prefacing the contents so that everyone could be in on the joke. Scientists did not bother to respond. It left Symmes discouraged but undeterred, for he reminded his frowning friends that all great visionaries had been laughingstocks at first.

He drafted additional circulars, dispatched new pleas, wrote columns for the press, and finally in 1820 went on the lecture circuit. He started in Ohio hamlets and then expanded his tour to the big cities of the East. By then, he had a few acolytes, as these type of people always eventually do. They were as loony as he, but they were handy for handling props and working the magic lantern slides.

The traveling troupe, tiny as it was, incurred expenses, and the venues of Philadelphia, New York, and Boston were costly to visit. Mary had to despair. Also, Symmes, kindly and soft-spoken, was more Wally Cox than Harold Hill, more Mr. Peepers than Robert Preston, a thin-voiced man with a round face and saucer eyes that sported a thousand-mile stare even when he wasn’t on a tear about the earth’s concentric inner spheres.

No wealthy patron appeared, and he did what all hopeless crackpots nowadays do when they can’t get reasonable people to pony up money for a harebrained idea. He went to the United States government. His petition for funding an expedition at the public expense was presented to Congress twice but was tabled both times, which everybody understood meant permanent rejection.

Poor Symmes was living two centuries too early and missed out on the age of the government grant as a given, the more absurd the project, the better. So it was that in the 1820s he didn’t score a government grant but inspired only jokes that after a time became jeers. He became notorious enough as a crank to have a little cliché grow around his name and theories. For a while, people who wanted a shorthand way to describe something as ludicrous called it “Symmes’s holes.”

The monument over the remains of John Cleves Symmes, Jr., in Hamilton, Ohio, features a globe open at the poles.

And by the end of the decade, that sort of reputation along with an empty bank account broke his spirit and ruined his health. He died on May 29, 1829, not yet 50.

But the life of John Cleves Symmes, Jr. taken in sum forms a strange parable. In a sense more significant than the preposterous theory he embraced, his life certainly highlighted the risks of public ridicule. But it also inspired a measure of private esteem given with eager hands and open hearts. Publicly, he fought rather than used his family connections, and he believed in an outlandish idea with a faith as passionate as it was unshakeable, as unreasonable as it was unreasoning. He paupered himself financially and spent himself mentally, while gradually making his name a byword for absurdity. His “public,” such as it was, became a jeering mob that forgot him as soon as he passed.

But something about Symmes made those in his private life intensely loyal and always loving. Because of that, they shielded him as much as they could with kindness as well as something more valuable. Mary and the children always told him that they believed.

We should all be so lucky.