He barked that his men, by the Eternal, would keep their weapons.

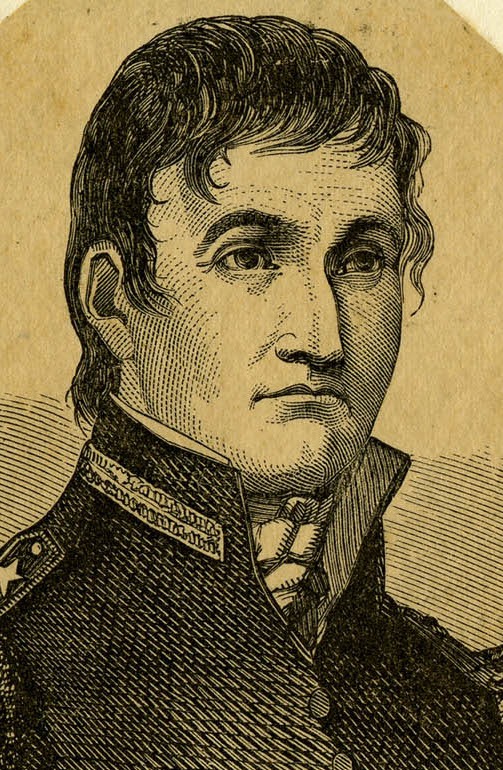

Andrew Jackson's War of 1812 got off to a disastrous start. By the advent of hostilities, he had been the major-general of the Tennessee militia, Second Division, for ten years without commanding men in the field, let alone fighting a battle. When war with Britain seemed certain, Jackson offered his 2,000 men to help invade Canada, but President James Madison’s administration merely acknowledged the offer and otherwise ignored it.

Madison had his reasons. Six years earlier, Jackson had in some way participated in Aaron Burr’s mysterious plans that the United States government eventually deemed a “conspiracy.” Burr was arrested and tried for treason. Jackson’s participation was slight, and he wasn’t alone in judging Burr innocent — a jury in Richmond refused to convict Burr — but the affair left him with a trail of enemies, many of them influential. He had railed against President Thomas Jefferson, Madison’s great friend and political soul mate, for arresting the wrong man, and he had made no secret that he thought General James Wilkinson was the real culprit in whatever evil plans were afoot. Jackson was so fixated on the perceived injustices riddling the Burr affair that he supported a challenger against James Madison’s presidential candidacy in 1808. “I’ll tell you why they don’t employ Jackson,” Burr at the time told a young New York politician named Martin Van Buren: “it’s because he’s a friend of mine.”

Nobody in Washington wanted Andrew Jackson’s services when the War of 1812 began.

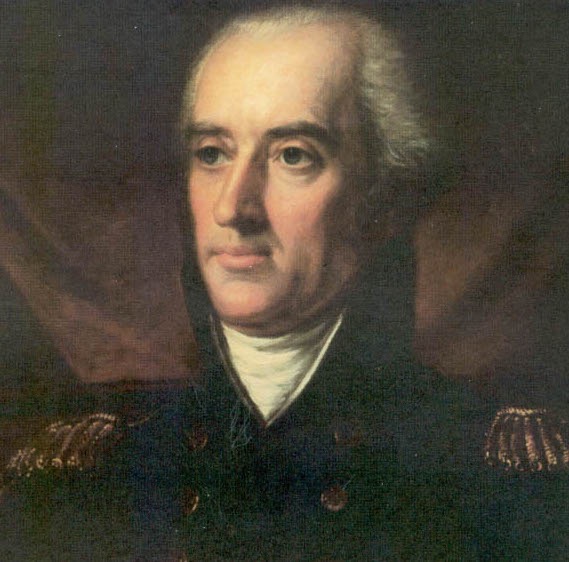

In 1812, Jefferson was in retirement at Monticello, but Madison was the president. James Wilkinson was still a senior general in the United States Army, just as he had been during the Burr affair when, in some people’s estimation, Jackson had slandered him. And so it was on October 21 of that year, almost four months to the day from the declaration of war on Great Britain, that Secretary of War William Eustis sent a request to Tennessee governor Willie Blount with a notable omission. The War Department wanted Blount to raise 1,500 volunteers for federal service to help James Wilkinson defend New Orleans. The snub was subtle but clear. Eustis did not mention Andrew Jackson. The government wanted any Tennesseans but him.

Blount knew that putting the state's men in service without the popular Andrew Jackson was politically impossible, especially if those men were to serve under the universally disliked James Wilkinson. It took him a while to decide, but Blount finally chose to defy the implicit wish of the Madison administration. Pulling one of the blank commissions from the stack the War Department had sent to Nashville, Gov. Blount scratched in Jackson's name as a major-general of the United States Volunteers. When he informed Jackson of Madison's call for soldiers, he spoke plainly: "You will command them." Blount refrained from telling Jackson that the federal government hadn’t wanted him.

Jackson didn’t like the idea of serving under Wilkinson, but he was willing to swallow the “bitter pill” to serve the country. He began assembling officers and men for the journey to Louisiana, but bad luck plagued the undertaking from its start. Brutal cold froze the Cumberland River and prevented the delivery of supplies, including weapons. Problems with pay had men grumbling as they shivered week after week in a makeshift camp with little to do but nurse their grievances. By the end of December, his army still in Nashville, Jackson sensed “the seeds of mutiny.”

Willie Blount made the decision to place Jackson in command of Tennessee troops headed for New Orleans by way of Natchez. Nobody outside Tennessee was happy about.

Blount had wanted to follow the traditional militia procedure of allowing the rank and file to elect field officers, but Jackson insisted on picking his deputies, and Blount reluctantly agreed. The result was a group Jackson knew and trusted. The topmost were not all tough men, but they were at least competent: Tom Benton and William Hall in charge of his infantry, John Coffee commanding his cavalry, Billy Carroll his brigade inspector, neighbor William Berkeley Lewis his quartermaster, earnest John Reid his aide.

Coffee was one of the tough ones, slow to speak and slower to anger, but that made every single word he uttered sound important or ominous, depending on his mood. His anger, once raised, made him dangerous beyond belief. The volunteers milling around Nashville with time on their hands liked their hard liquor and raucous carousing. They wanted their government to pay for both and could get feisty if denied one or prohibited from the other, and especially if the money went missing. Col. Coffee could calm things down just by showing up. Swaggering men would stop still, go silent, and study their shoes. Everyone had heard about Coffee's anger. Nobody wanted to see it.

Quiet and deliberate, John Coffee rarely lost his temper. When he did, it was memorable.

By the start of 1813, after the soldiers finally received pay, Jackson believed he could begin the journey to New Orleans. He had to cover the expedition’s expenses with a personal loan of $1,650, but his high spirits more than compensated for the imposition. He wrote to the acting secretary of war James Monroe (Eustis was fired after the war’s early military disasters) that his force numbered 2,070 men. His pride that it exceeded the War Department's request was evident. Nor was this all. Everyone, said Jackson, was primed to answer "the call of their country to execute the will of the Government; who have no constitutional scruples; and if the Government orders, will rejoice at the opportunity of placing the American Eagle on the ramparts of mobile, Pensacola, and Fort St. Augustine. And effectually banishing from the southern coasts all British influence. At New-Orleans I shall anxiously await the orders of the Government."

Acting Secretary Monroe might have winced over the bluster and the remark about men willing to act without the restraint of "constitutional scruples." Moreover, the official explanation about defending New Orleans was supposed to mask the government's real plans, which involved offensive operations against Spanish Florida. Jackson's way of announcing things best left unsaid was one of the many reasons the government was wary of him. Monroe was fortunate not to be in the War Department when Jackson's letter arrived because John Armstrong had taken over the department on January 5. But then again, Monroe would have his chance to wince later.

Jackson started from Nashville on January 10, but the bad omens continued. At Natchez, several letters from Wilkinson were waiting for him. The first was overly cordial, almost syrupy, but the others were strangely evasive and defensive. All of them emphasized that Jackson was not to come to New Orleans. Among other impediments, Wilkinson said, he had no place in New Orleans to lodge a couple of thousand Tennesseans. Another letter told Jackson to be ready for hot work near Mobile or Pensacola but repeated the order to stay put in Natchez.

These were troubling communications. At first, Wilkinson promised shelter and provisions, but days became weeks as Jackson remained almost 200 miles north of New Orleans with his men exposed to the elements and forced to forage for food. Finally, in mid-March, Jackson received a short note from Secretary of War Armstrong telling him, in so many words, to go home. His men were no longer needed and were consequently dismissed from the service. He was to turn over all federal property to Wilkinson, especially weapons, and return to Tennessee.

Secretary of War John Armstrong thought he could simply dismiss the Tennessee Volunteers from the service with no concern about their situation. Andrew Jackson saw it differently.

It was a stunning blow, and Jackson had difficulty understanding it. At first, he thought it might be a mistake. He muttered that Armstrong "must have been drunk when he wrote" the dismissal order. But then he began to believe something worse. He did not know that the War Department's decision to dismiss the Tennessee Volunteers was a result of Congress’s refusal to fund a West Florida invasion, so he immediately suspected a hidden purpose behind the entire episode. Until Jackson had objected, Wilkinson had been trying to enlist the Tennessee Volunteers in the regular army. Jackson was convinced that a conspiracy against him was underway. He believed that the order to turn over weapons was meant to make his men helpless as they marched through potentially hostile Indian country. The option of being scalped or going into the regular army made recruiting all the easier for Wilkinson. Jackson became quite angry as he thought about it, and there soon followed one of his explosions.

It has never been clear what Wilkinson was up to when he stalled Andrew Jackson while trying to recruit away his soldiers. He seems to have thought the terms of their dismissal would increase his manpower while getting rid of Jackson. He was wrong.

He fulminated with a purpose because he had more than 2,000 men more than 800 miles from home with no money, no food, and no transportation. Jackson barked that his men would, by the Eternal, keep their weapons. He would not see them stranded, hungry, and helpless, and he would not see them scooped up by Wilkinson like so many wastrels at a back-alley saloon.

Instead, Jackson would take everyone home. He shamed Wilkinson into providing enough rations for three weeks. He borrowed $1000 on his own security to purchase or rent eleven wagons to convey his increasing numbers of sick.

Marching toward Tennessee, the Volunteers faced dense woods, hostile Indians, and high running creeks. As more men became sick, the wagons would not hold them, and they were falling out from the march. Jackson slid off his saddle and lifted one of them on his horse. His officers wordlessly followed the example. Mile after mile and day after day passed. The rations would not last, so Jackson stopped eating. The men noticed, of course, and at first, they called him only "Hickory" in tribute to his toughness, but because they were mostly boys, everyone looked "old" to them. He soon became "Old Hickory." Andrew Jackson was forty-six years old.

When he brought them to Nashville at the end of April 1813, he looked a hundred. The government didn't want him, and the entire expedition had been a wasteful embarrassment. But the volunteers wept when they saw the town and cheered when he spurred his horse toward the Hermitage and Mrs. Jackson, his Rachel.

The war, such as it was, was over for him, it seemed. And yet, his decision to defy his government and keep the weapons was fateful. His resolve to bring his men home was pivotal for everything that followed. The upcoming Creek campaign would be a test, and his miraculous victory at New Orleans would be spectacular. But that April day in Nashville when weak men found the strength to fill the air with loud noise, that was something more. They were amazed by their deliverance and by the author of it.

Andrew Jackson had turned the sobering humiliation into his finest hour.

— Adapted from The Rise of Andrew Jackson: Myth, Manipulation, and the Making of Modern Politics