In March 1943, the prestigious Theater Guild’s upcoming musical production was in a great deal of trouble. The routine of putting a show through out of town tryouts had proved troubling. New Haven was bad enough, but when the show pulled into Boston, it became a nightmare. Half the cast was sick with the croup, and the choreographer had infected the dance troupe with German measles, enhancing her reputation for being difficult with the taint of a jinx. One of the producers was running such a high fever that the male and female leads spent their days placing ice packs on her forehead. Tempers were flaring, and tantrums by chorus members and principals alike interrupted routine run-throughs. Nobody liked the title. The thing was less than two weeks away from opening on Broadway, and the assessment among insiders was blunt: “No gags, no girls, no chance.”

They were calling it Away We Go!, a sad attempt to disguise the turkey as a songbird, but people in the know were calling it “Helburn’s Folly,” after its fever-ridden producer, Theresa Helburn. Her idea for a cowboy folk opera in the spirit of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, also a Guild production from a few years back, was troubled from the beginning when efforts to scare up investors had revealed smart money as just plain scared. “I don’t like plays about farmhands,” became a running motif in tony upper Manhattan apartments where potential pigeons had listened to bright pitches before refusing to pitch in. Casting had been a doleful project, with mega stage star Mary Martin saying no, and mega screen star Shirley Temple choosing to pass. “Not my kind of show,” Groucho Marx had said. It was, after all, about farmhands.

And it was dark. Its inspiration was a play by Lynn Riggs, a half-Cherokee from Oklahoma, whose Green Grow the Lilacs in 1931 showed how love, jealousy, and murder could tear apart people much like it had Gershwin’s residents of Catfish Row, except Riggs’s characters were white. But the composers who could write a western Porgy — say Jerome Kern or Aaron Copland or Kurt Weill or Ferde Grofé — didn't want to touch Green Grow the Lilacs. Terry Helburn finally approached Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, and she might have been surprised that Rodgers agreed to come on board. Others certainly were. Lilacs was worlds removed from the frothy revues and fluffy musical comedies that Rodgers and Hart had turned into a successful franchise for almost two decades.

In fact, Larry Hart was most surprised of all. He rightly concluded that his trademark sophisticated rhymes — in “I’ll Take Manhattan” he pulled off an internal one: I'll go to Greenwich, where modern men itch to be free — wouldn't work out so well in a show about, well, farmhands. It made cynics suspicious about Dick Rodgers’s motives. Perhaps he had not wanted to join the Lilacs team so much as he wanted to lose Larry Hart, who by 1943 was never sober and rarely pleasant. Hart slurred a farewell, and Rodgers signed up a fellow who didn't mind writing lyrics for farmhands at all. He couldn't afford to mind. Oscar Hammerstein II hadn’t had a hit in years. He was coming off a string of ten straight flops.

Little wonder that when this conglomeration of unlikely suspects took Green Grow the Lilacs into its distressing March tryouts, there was foreboding about a flop. They had been forced to rename the show Away We Go! because Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer had optioned the play and wouldn't budge on the title. Just another thing that wasn't quite right and seemed to foreshadow a short run in New York.

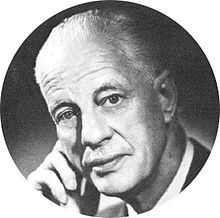

And yet, and yet — while on the stage of Boston’s Colonial Theatre the dancers with measles limped through their steps and the sickly singers croaked out Dick Rodgers’s tunes and Oscar Hammerstein’s words, a tall, quiet man stood in the wings watching, listening, taking notes, and scribbling revisions on staved paper. The 28-players in the orchestra pit, a larger than average number for a Broadway musical, would wait until the quiet man finished his work, always at this point a work in progress, and they then would pass the sheets to one another, look up at the conductor, and play. The tall, quiet man was never rattled nor anything but pleasant, and while always busy, he invariably had time to listen to a complaining chorine or have a cup of coffee with the lad who just couldn't master the modulation in an intricate melody. It was the unflappable quiet man who made everybody hope that maybe, just maybe, this wasn't a flop.

Dick Rodgers had signed Robert Russell Bennett to the production team at the same time he was hiring a stage manager and a conductor, and with good reason. Among all the people to join the show, Bennett had the most impressive record of hits. He also seemed the most fitting fellow to understand a show about farmhands. Rodgers and Hammerstein were Ivy Leaguers, Columbia men, with Rodgers rounding out his musical education at what became Juilliard. Bennett, on the other hand, was a Midwesterner born in Kansas City, who grew up on his grandfather’s farm in the little community of Freeman, Missouri. But that wasn't the reason Rodgers hired Russell Bennett. Shortly after arriving in Boston, Away We Go! was retitled, in part because the little tune Rodgers had noodled out on a piano in the space of ten minutes was orchestrated by Bennett into a rousing centerpiece whose sweeping melodies and raucous celebration shouted its announcement as a namesake. The tunes you hear in Oklahoma! were composed by Richard Rodgers, but the music is Robert Russell Bennett’s.

It was typical practice. All composers of Broadway musicals employed a handful of orchestrators and a legion of copyists. George Gershwin, except for Porgy and Bess, never scored his shows. Nor did Cole Porter, Kurt Weill, Irving Berlin, or Jerome Kern theirs, though Kern was egocentric enough to provide extensive sketches and detailed instructions, as he did with Showboat. Kern’s orchestrator for that show, the fellow responsible for making “Make Believe” lighthearted, “Can’t Help Loving’ Dat Man” sassy, and “Ol’ Man River” powerful, was Robert Russell Bennett. In fact, any show of any substance from the early 1920s through the mid-1970s that featured the tunes of Broadway’s heavy hitters was put to music by Robert Russell Bennett.

He had worked with Richard Rodgers several times before Oklahoma, so the two knew each other’s methods. Rodgers was a minimalist whose piano treatments were often barebones melody lines sometimes roughed out with notations for patterns and chords. The technique made him lightning quick. He could take a lyric that Hammerstein had labored over for days and put an original and memorable melody to it in minutes, a pace that had him estimating about six days spent writing all the tunes for Oklahoma. These shorthand notations were taken up by Bennett and turned into the bright accompaniments and exciting harmonics of Oklahoma’s songs as well its incidental music. Even more, Bennett apparently wrote the entire dream-ballet that ends Oklahoma’s first act. In its voluminous archives, there isn’t any music in Rodgers’s hand for that pivotal fifteen-minutes of the show.

Rodgers made no secret of his debt to Bennett, whom he praised for his “lack of ham” and resistance to “corny” musical tricks. Bennett's orchestration of "The Surrey with the Fringe on Top" didn't resort to percussion lines to imitate clip-clopping hoofs, and Rodgers was confident that Bennett would “make those wheels go around” and “keep that open-air, farm feeling” without any cheap tricks.

Despite humble beginnings, there had never been anything cheap about Russell Bennett, because nothing had been easy for him. His dad George was a talented musician who nevertheless was something of a knockabout freelancer picking up gigs with the Kansas City Symphony and forming a band of semi-professionals when the Bennetts moved to Freeman. His mom May was a New Englander descended from the Mayflower Bradfords. She taught piano, chafed at rural Missouri’s provincialism, and dismissed popular music as “trash.” She consented to live in Freeman only because little Russell at age four came down with polio, and the fresh air of Grandpa Bennett’s farm might make him comfortable if not ambulatory. While bedridden, Russell taught himself to read with the same fierce resolve that forced him to walk. Even before he turned six, his parents were astonished by his courage, good cheer, and the emergence of a prodigious ability. He had harmony in his blood and talent in his genes. He could play the piano by ear but quickly mastered more than musical notation. Russ could transpose music into different keys on the fly, never missing corresponding sharps and flats, all by seeming reflex. As he grew older, Russell Bennett studied under talented teachers, including Nadia Boulanger in Paris, but all found they could not teach him much more than he already knew. Music was more than second nature to Russell. It was an instinct.

He moved to New York after World War I and worked briefly as a copyist before his talent landed him a job as an orchestrator, first for a little show called Daffy Dill where he met Oscar Hammerstein, and then for a revue called George White’s Scandals, which introduced him to George Gershwin. In those days, almost every prominent personage in Broadway musical theater was a Jew, and one might imagine that a kid from Kansas City would have been the proverbial fish out of water, but Russ Bennett liked everybody, and everybody liked him right back. And it helped that Bennett was supremely gifted. Jerome Kern, a self-described son-of-a-bitch, ran through collaborators with blithe abandon, but Russ Bennett was unassuming and massively talented. Listening to Russ Bennett’s arrangement of “Ol’ Man River” made Jerry Kern weep.

George Gershwin and all the rest of them wanted Russ to score their shows whenever possible. Bennett thought in musical notations on staffs the way most people think in words, which was why he was able to sit on speeding trains or in the wings of theaters bustling with rehearsals and scribble out notes without the aid of any musical instrument. He always took everything in stride with the same calm resolve he had used to beat polio. But what was most remarkable was the pace of the stride he was taking it in. Most composers and orchestrators work in sketches that they gradually fill in and polish, the way a painter will overlay shadows and tints to achieve depth and perspective. Robert Russell Bennett wrote scores as a linear exercise, notating one measure at a time for melody, harmony, counterpoint. rhythm, pace, and volume for the entire ensemble, filling staved sheets rapidly, and always in ink, for he never made mistakes. He then returned to the beginning for the next measure, and then the next, and next. It was as if everyone else was laboriously painting pictures in gradually emerging and meshing musical thoughts while Russ Bennett snapped a photograph of an entirely realized composition, expertly shaded with perfect exposure artistically arranged to arrest the ear the way an exquisite photograph captures the eye. It was how he was able to write so quickly and so well.

Irving Berlin thought about music this way by hearing it in his mind as a realized whole, which is why Bennett admired Berlin so much. They were kindred spirits, but with stark differences. Berlin never learned to read music, couldn't write a note of it, and was a middling piano player, at best, habitually playing melody lines and simple chords on the black keys of a piano he had built with a lever that could change keys by shifting its hammers. The other difference between Berlin and Bennett was revealing and is revealed by the time Berlin was playing a melody for Bennett and struck a chord that displeased them both. “That’s not it, is it?” Berlin asked. Bennett said, “Well, that’s not what you heard,” and Berlin knew exactly what that meant. “What is it, then?” Berlin asked, and Bennett tried a chord, a wrong one by Irving Berlin’s expression, and another, which still wasn't right. Bennett’s third chord lit up his friend’s face. “That’s it!” he exclaimed.

The tall, quiet man of Amercan musical theater.

But Robert Russell Bennett not finding the correct chord right away was a small, sad commentary on his efforts to compose original music. Almost all of his compositions were seemingly a tribute driven by his mother’s notions of “serious” music, but they are now mostly forgotten and almost never performed. He could be original, but his work inclined to novelty, on the order of Leroy Anderson’s “Syncopated Clock,” but rarely with Anderson’s already limited charm. Bennett otherwise pivoted between grating modernism that featured polyphony (which was strange considering his focus on melody in his orchestrations for the stage) and thin, corny treatments of themes he seemed to crank out with little thought. Over the course of a long life, he composed almost 200 original works that included symphonies, concerti, sonatas, chamber pieces, even an opera. But critics tended to judge his original works “stale and pretentious,” and complained about “slick orchestration” and “constant wittiness.” His Suite of Old American Dances is remarkable for escaping the mixed reviews, playful and compelling pieces that are unique in the Bennett canon for becoming a standard part of concert programs.

He was professional enough to know that much of his original work was subpar, but he never despaired, possibly because he was too busy. Given an idea, he could take off, as when Richard Rodgers gave him a handful of melodies on less than twenty sheets of paper. Bennett took that and produced almost twelve hours of music for the 26-episode television series Victory at Sea. It is a triumph of imagination in infinite varieties that Dick Rodgers freely conceded made his music better than it was. The NBC Orchestra finished its first rehearsal of the opening half hour of Robert Russell Bennett’s score under his baton. The musicians were hushed and sat stock still for a few seconds in the silence after the last triumphant notes. They then leaped to their feet applauding and cheering the tall, quiet man on the podium. He was embarrassed.

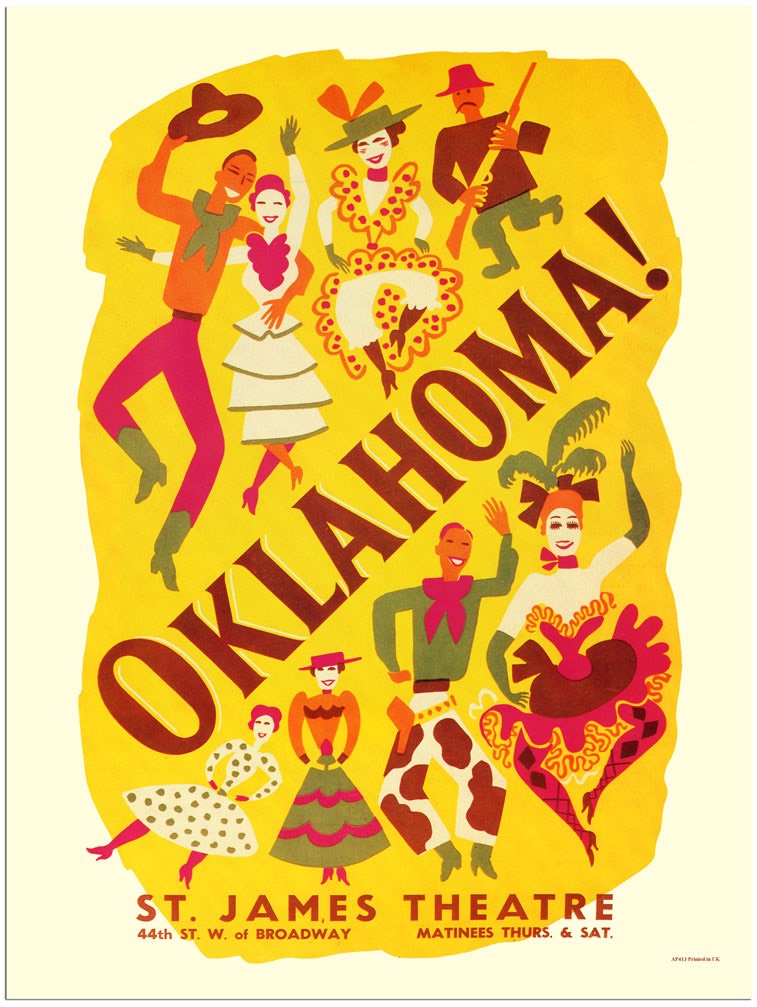

When Oklahoma! opened on Broadway in the St. James Theatre on March 31, Russell Bennett had left his deft touch and signature style on a score that captivated that audience that night and would continue to captivate audiences for more than 2,000 performances to come and in revivals to this day. Servicemen from all over America lined the back of the theater during the war, boys headed for harm’s way and uncertain they would come home. Their throats tightened and they looked down when they heard “home” in Dick Rodgers’s tunes and Russ Bennett’s music. The show set a record for the longest run of a musical until it was broken by another boffo hit musical in the 1950s.

Guess who orchestrated My Fair Lady.

_______________________________

We want to thank Dr. Ben Hawkins for his excellent biography of Robert Russell Bennett and especially for his reading this post to save of us from the errors of laymen. When he is not helping out hapless scribblers, Ben is a senior professor and the Program Director for Music at Transylvania University. All this, we should note, is in addition to his being a gentleman and a scholar.