And the Earth did move. . . .

At the beginning of the second decade of the 19th century, a persuasive Shawnee named Tecumseh traveled from his home near the Great Lakes to visit southern Indians. He presented to them a plan for reclaiming lands lost to the inexorable advance of white settlement. Tecumseh envisioned a pan-Indian movement that would put aside ancient rivalries and tribal differences. All would again embrace the old Indian ways, again show reverence to the Great Spirit, and would rekindle the traditions of their fathers. Spiritually braced, they would become physically invincible. They would join as one to raise an irresistible multitude. They would wage remorseless war. From the falls at Niagara to the waters of Mobile Bay and all points behind and between, they would drive whites eastward and into the Atlantic Ocean.

Tecumseh

Persuasive or not, his message produced mixed results in the Creek Confederation of the Southeast. Tecumseh’s plan directly contradicted the one put in place by the United States government twenty years earlier. The American “civilization program” encouraged Indian assimilation into white ways, especially regarding agriculture. The idea was to make them peaceful neighbors rather than hostile obstacles to white settlement. On his visit, Tecumseh condemned the adoption of white culture and chastised villages that had embraced it. He chided Big Warrior, the assimilationist headman of the village of Tuckabatchee. Tecumseh declared that when he returned to Detroit, he would stamp his foot. They would know he had done this, he said, because the ground a thousand miles from him, the ground where they now stood, would tremble.

And thus it was beginning in December 1811, that the earth in the Mississippi River Valley did more than tremble. It convulsed in a major earthquake. Two more followed in the months to come, and more than 2,000 tremors of varying intensity shook the ground. Seismologists call it “The New Madrid Sequence” after the main fault in the region.

It is a relatively recent discovery in the long span of human history that the continents are not unified land masses. They are instead a patchwork of huge tectonic plates that float because they are anchored to nothing. They move more or less all the time, but imperceptibly. Their shifting usually measures in fractions of an inch and can take years to occur. The earth causes this with its never-ending vulcanization that piles up new undersea acreage at the edges of the continents. The plates make way by moving, and ordinarily, they easily slip against one another at their edges, which seismologists call faults.

Long before Tecumseh was traveling among the southeastern Indians, and unknown to him or any of his hosts — or to anyone for that matter — the plates shifting against each other in the Mississippi Valley had snagged and had stopped making way. Stresses intensified over time as the plates stored up terrific potential energy. When the pressure became too great to contain itself, it transformed from potential to kinetic energy — from the possible to the actual. The plates of the New Madrid Fault made up for lost time by adjusting themselves quickly. Shifts that should have taken centuries happened in moments.

All prophets should be so lucky, and it’s never been clear how Tecumseh’s declaration was connected to an incident that can only be described as cataclysmic. Even cataclysmic is something of an understatement. As seismic events go, the one triggered by the New Madrid Sequence was a humdinger.

It began December 1811 as a low but audible rumble below the ground. It became rapidly louder until it seemed to come from everywhere, a gut-punching bass punctuated by ear-splitting crackling and grating sounds that many compared to the sound of a thousand carriages being driven rapidly across pavement.

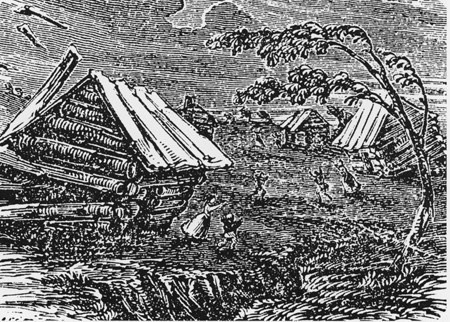

In combination with the sound, the ground began to move, first shivering a bit but soon shaking with such force that neither man nor beast could keep his feet. In some places, the ground resembled an ocean of waves rolling to the horizon. Entire forests rose and fell on the rolling waves of earth like wreckage on a sea. Crossing forces randomly stopped the steady rolling and made the ground appear to boil, toppling trees or leaving centuries-old oaks upright but split into two halves at their trunks. Massive waves of earth resembled breakers heading toward a beach, gaining a towering height until they exploded with the thunderous report of a hundred-gun artillery battery. Cracks opened and spewed hissing water and hurled sand and pyrites hundreds of feet into the air, then closed again with the grating sound of a colossal millstone.

The gound became like a stormy ocean

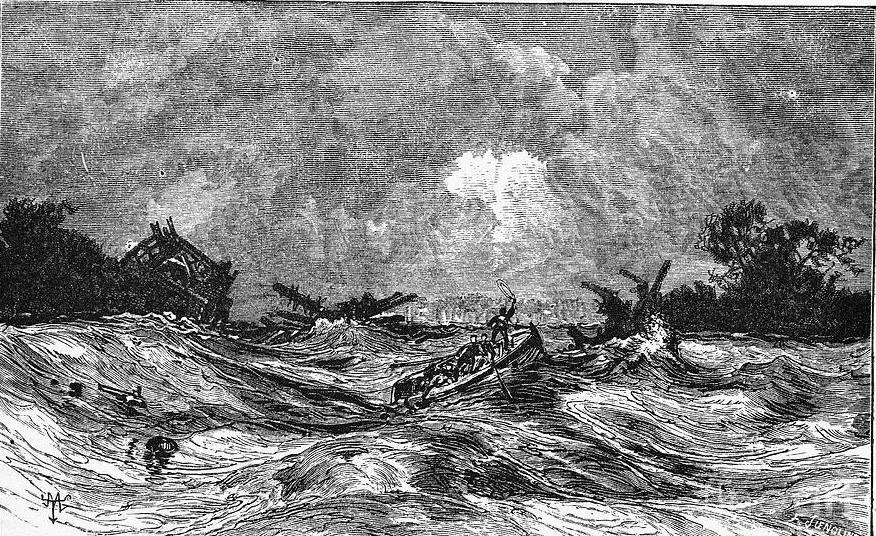

The Mississippi River became so turbulent that it caused massive landslides at bluffs and carved long spans of its banks away. The river swallowed up groves of towering cottonwoods, swamped boats, and obliterated islands while creating new ones. Faults across the Mississippi caused rapids and waterfalls. The river rose so rapidly it reversed its flow and ran backward. Ancient lakes disappeared, and new ones came into being in a matter of hours. Extrusions of sulfurous gasses contaminated miles of the river and made prized limestone springs useless.

A man watched mesmerized as the river separated across its mile-wide length into two parts. Its waters cascaded into a seemingly bottomless abyss. It just as quickly closed up. Another saw the river rapidly retreat from its banks to form a mountain of water that stood poised for a few seconds before rushing back to the banks with such force that it obliterated everything, including one of those large groves of enormous cottonwoods.

This went on for minute upon interminable minute, until it stopped. Or actually, until it paused. Because the tremors continued to break out after the first main quake on December 16, 1811. The tremors were bunched up or were single little jolts that jarred the land day and night, week upon week. They were so frequent that people even got used to them and found them annoying rather than frightening.

Then in mid-January, the tremors seemed a bit sharper, the grating more pronounced, the rumbles a bit deeper. On January 23, 1812, another major earthquake hit the region that produced “strong undulations” for about 5 minutes, an eternity in which all the fantastic seismic events of December were replayed. On January 27 a sharp jolt lasted only an instant but resembled in force the major one of four days earlier. Residents of the region were rattled and jumpy as hundreds of small aftershocks led to sharper agitations on February 4. These noticeably stronger jolts occurred for two days.

Then on February 7, it happened. All hell broke loose. “Alarming oscillations” terrified people who had gotten used to the smaller stuff. This last major event of the New Madrid Sequence was its showstopper. The previous two major quakes paled in memory during what, for all the world, looked like the end of it.

The promising little community of New Madrid was simply erased from the face of the moving earth. The same fate befell surrounding settlements. The quake devastated the region around New Madrid for hundreds of miles, turning the once fertile and lush landscape into a “melancholy aspect of chasms of sand covering the earth, of trees thrown down, or lying at an angle of 45º, or split in the middle.”

That was in the immediate region. The area of severe shock was much larger, anywhere from 30,000 to 50,000 square miles.

The Mississippi River was so turbulent that it reversed course

Indeed, the New Madrid earthquake of February 7. 1812, shook the continent from the Rocky Mountains to the Atlantic Ocean. The earth shivered at different levels of intensity over an area of 1.5 million square miles from Canada in the North and the Red River in the South to Boston, New York City, Annapolis, Charleston, and Savannah on the East Coast. At the Executive Mansion in Washington, President James Madison felt this earthquake. It rang the Georgia State House bell in Milledgeville, rattled crockery on New York’s 5th Avenue, and gave people motion sickness in Cincinnati. Charleston, South Carolina, heard a low rumble then felt a sharp jolt that stopped clocks throughout town. For ten long seconds, St. Philip’s steeple bell tolled. The end of the world seemed possible with such a doleful announcement.

Yet, this time, it wasn't the end of the world, at least for the part that lay beyond the immediate reach of the New Madrid Fault. Statisticians tells us that for all the noise and violence, there was little loss of life because the Mississippi Valley was so thinly populated in 1812. The families who experienced this “little” loss of life would have doubtless differed as to its magnitude.

Of course, Tecumseh’s talk of trembling earth was coincidental to these events. The earthquake certainly wasn’t caused by his stamping foot: he wasn’t even in Detroit to stamp it when the New Madrid Sequence began.

But why did he promise such a result in the first place?

Possibly he had heard Indian oral traditions about violent earthquakes in the heartland, for something memorable had happened in the region during the 1500s. Also, during the span between 1776 and 1804, at least five fairly major seismic events shook the region along the Mississippi River, in the Illinois Territory, on the shores of Lake Michigan, and even at Niagara Falls. Tecumseh almost certainly knew about these.

We will never know, though, whether he was gambling on another pending earthquake or had some uncanny sense of something about to happen. But if Tecumseh had been just talking in riddles before the New Madrid Sequence, whites did much the same thing after it. Misguided theories multiplied in the “ cientific community” about what had caused the New Madrid earthquakes. They were, it was said, the result of abnormal phases of the moon, irregular ocean tides, drops in barometric pressure, or even buried treasure triggering a chemical reaction.

It made just as much sense for Indians to believe that Tecumseh had stamped his foot.

Only two things are certain from all this, however. One is that it was irrelevant whether or not Tecumseh’s divination had any basis in reality. The coincidence of his prediction with the New Madrid earthquake made him a prophet without peer among Creeks. They came to believe they were at last armed with both the truth and supernatural powers. The origins of a major Indian war in the Southeast lay in these beliefs.

The other certainty is timeless: the farther away from the last earthquake, the closer to the next one. The two centuries that separate the New Madrid Sequence from our time are less than a blink of the earthly eye, and the earth still moves in that part of the world, except when it doesn’t and again starts storing up its terrible forces. In 1895, an earthquake in the region radiated for a thousand miles.

In short, there is neither art nor artifice in predicting that there will be another New Madrid Sequence. The only question is when. Perhaps it will be on the day when Tecumseh, somewhere, stamps his foot.