For many Americans in the third decade of the nineteenth century, the nation’s capital had become as alien as the mountains of the moon. In one sense, this did not surprise. Concerns about establishing a federal district whose sole purpose was to host the capital were older than the government itself. During the debates over drafting and ratifying the Constitution, Virginia skeptic George Mason had predicted that such a locus of power would “become the sanctuary of the blackest crimes.”

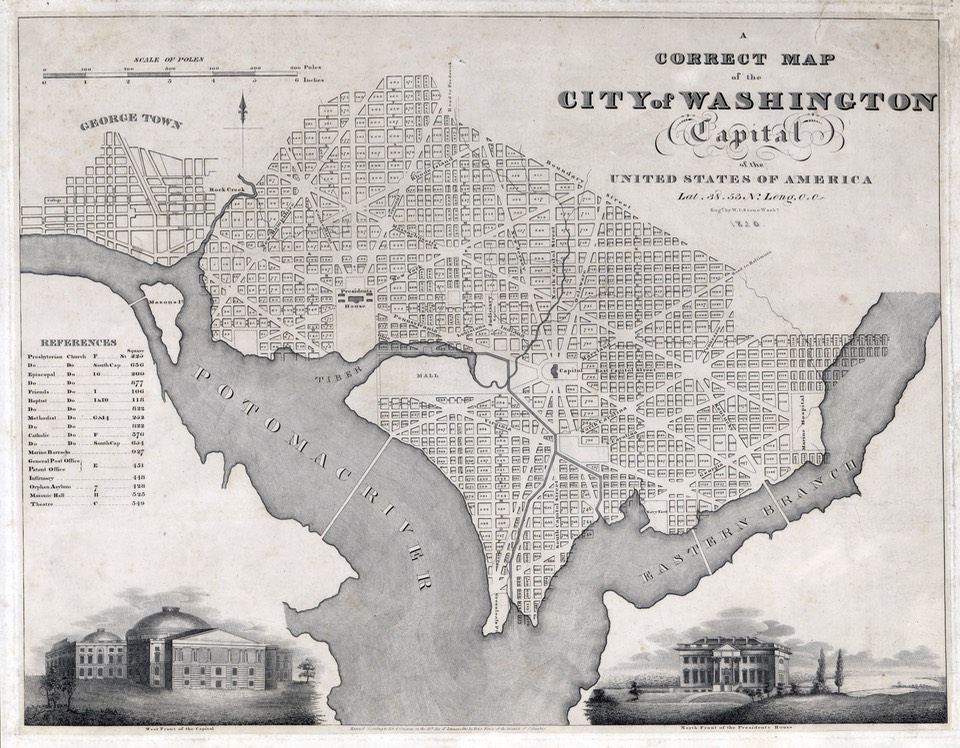

Washington DC in 1820

Foreigners found the place baffling, a village “only kept alive by Congress.” And for every admiring description—a Portuguese minister marveled over “the city of magnificent distances”—there was a less flattering one about wallowing pigs, wandering dogs, and distances more peculiar than impressive. “The houses are here, there, and no where,” said a British actress, who noticed how the streets were only “roads, crooked or straight, where buildings are intended to be.” There was a considerable amount of open space, such that “in the midst of town, you can’t help fancying you are in the country.”

Ordinary Americans, however, had begun to doubt that a bucolic setting promoted wholesomeness. Washington’s problem wasn’t being half-finished but the “congregation of government offices . . . where political characters, secretaries, clerks, placeholders, and place-seekers . . . congregate.” Men on the make jostled at the public trough, some to dispense favors, others to receive them, in a dizzying whirl of intrigue and disregard for the public trust. For every quid, there was a winking quo. For every itching back, there was one hand to scratch it and another opening its palm for the grease of this piece of legislation or that bit of government largesse.

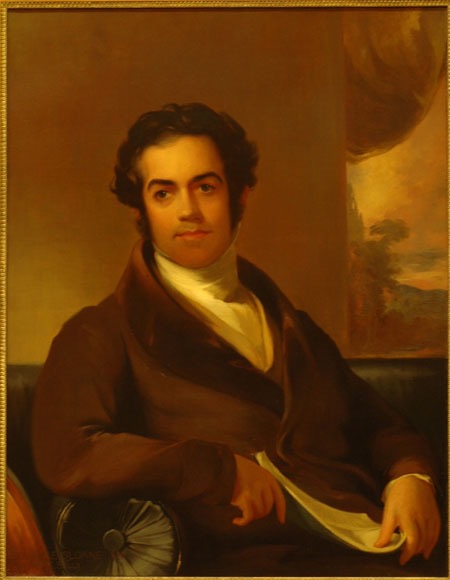

In the midst of dubious dealings, social frivolity added to the impression that Washington’s politicians were not competent to solve any problem larger than assembling a stylish guest list. The capital’s denizens “lead a hard and troublesome life,” lawyer, linguist, and bibliophile George Ticknor said with tongue in cheek. After all, President Monroe and his cabinet “entertain strangers . . . in a very laborious way.” Ticknor spent four of his thirty-four years in Europe for seasoning, and the time had well prepared him to observe a place where “society is the business of life.” He concluded that “people have nothing but one another to amuse themselves with; and as it is thus obviously for every man’s interest to be agreeable, you may be sure very few fail.” For many Americans, Ticknor could have been describing a European court with powdered ladies and mincing men.

“So much bowing—so much simpering—so much smiling—so much grinning,” muttered Attorney General William Wirt about New Year’s festivities. “Such fawning, flattering, duplicity, hypocrisy.” It made Wirt’s head spin before it made his stomach turn. People in Washington took all the wrong things seriously, it seemed. Wirt introduced an officer from the War Department to Henry Clay and got the man’s name wrong. “I’ll be d[amne]d,” Clay chuckled as the offended fellow strode away, “if you don’t have a challenge [to a duel] in half an hour.” Even those who had no stomach for simpering smiles seemed to avoid them out of snobbery, not refinement. “There will be a drawing room [reception] this evening, for the first time this season,” Massachusetts congressman Jonathan Russell sniffed, “but as it is vulgar to go [to] the first I shall of course stay at home.” Russell’s arch “of course” said it all.

William Wirt

George Ticknor was a dazzled traveler who believed that “the only objection to society at Washington is, that there is too much of it.” But much of the rest of the country seethed over the capital’s gaiety while the burdens of just getting by weighed heavily on Americans unaware that attending a party at the wrong time was unsophisticated. The charitable explanation was Washington’s incompetence. The sharper one was that the politicians didn’t care. A visitor needed to watch Congress in action only briefly before making references to the capital as a “terrestrial paradise” where “the Capitol had its full complement of jackasses who are searching after immortal glory.” Elaborate procedures, endless and digressive debates, points of order, yielding the floor to “my friend” (often actually a bitter enemy), and an abundance of tricks made it all appear vacuous. The government seemed intent on avoiding important business. “Such things cannot fail to make us very ridiculous abroad,” an informed citizen reported, more in sadness than in anger. “They weaken the attachments that ought to prevail at home,” he sighed. “The people at large are getting heartily tired of this abuse of the representative systems.”

George Ticknor

Andrew Jackson’s friends understood the general mood of the country about its elected officials, and they planned to portray him as an honest hero who would return the country to its virtuous roots. Other men were more prominent politically, but that also was an advantage for Jackson, because voter dissatisfaction focused on the very government these well-known men presided over. Jackson’s military exploits had made him a national celebrity, but the nature of those exploits had also established him as a man of action. The Pennsylvania cowherd pulling udders a couple of hours before sunrise, the Alabama yeoman harnessing his plow by the pink light of dawn, the Louisiana boatman hauling his lines, the mechanic in Charleston, the laborer in New York—men like these all across the country did not know it was uncouth to go to the first party of the season, but they did know something about paying bills and keeping promises. Stephen Simpson, Sam Overton, Henry Baldwin, John Coffee, William B. Lewis, John Eaton saw these people and how their eyes lit up when they heard Andrew Jackson’s name.

At the same time, these ordinary Americans were gaining the means to become an irresistible partisan force. The American Revolution had planted the seeds for surging democracy, but the politics of deference had stunted them for decades. That situation began to change before the War of 1812 and continued through the early 1820s as citizen demands for more political participation became impossible to ignore and difficult to suppress. States responded by gradually extending voting rights to white adult males regardless of how much property they owned.

In tandem with these changes, many states modified the way they selected electors to the Electoral College. For years, the exclusive nature of public affairs had state legislatures designating electors, but after 1820, eighteen of the twenty-four states would choose electors by popular vote. Five of the eighteen states—Indiana, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, and Tennessee—split their popular vote into districts, which abandoned the winner-take-all system of the other thirteen states, to make decisions even more reflective of local will. The six remaining states—Delaware, Georgia, Louisiana, New York, South Carolina, and Vermont—still had legislatures choose electors, but the methods varied. New York, for instance, split electors based on proportional votes in the legislature rather than giving all to one candidate. In sum, these changes made popularity imperative for presidential candidates, which in turn made elections more complicated for them.

For the right type of candidate, however, it made elections simpler. Expanding democracy meant the rejection of the politics of deference, the traditional system in which lower classes conceded governance to their social betters because of their supposedly superior wisdom. The financial Panic of 1819 increased this desire for social leveling. The common people disdained the idea that the only men qualified to run the government were those with the mysterious “talents” implied by membership in the ruling class. Whether occupying county, state, congressional, or even a presidential office, the high-born were judged as nothing more than highfalutin. Jackson could oppose government aid to victims of the panic all he wanted to, because what he believed was less important than what he was. Jackson’s friends denounced Washington’s elite as incompetent and uncaring. They condemned the congressional caucus choosing presidential candidates as undemocratic. In the process, they laid the foundation for a new political movement. A growing number of people were certain Andrew Jackson would go to a party if invited, no matter when it was held. His supporters planned to have the country throw him one.

— Excerpted from The Rise of Andrew Jackson: Myth, Manipulation, and the Making of Modern Politics