Where friendly gals daubed off soot smudges from the latest fire and sat with lonely men who dreamed and dared.

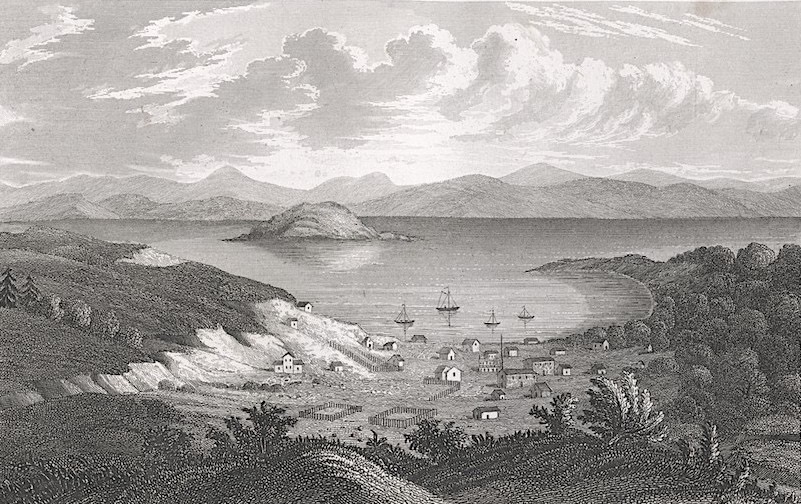

In 1848, San Francisco was a sleepy little village of fewer than 2,000 souls planted in an unlikely if picturesque place. Small dwellings and modest stores along rutted dirt streets dotted steep hills. An expansive bay was host to the occasional ship that anchored a half mile out from shore in deep water because the village itself fronted on a shallow pool called Yerba Buena Cove.

The sleepy village of 1848

The real activity was up in the Sacramento Valley along the American and Sacramento rivers where an empire builder named John A. Sutter was working to transform his 50,000-acre Mexican land grant into a prosperous agricultural colony. A bit farther along in the serene Coloma Valley at a bend on the South Fork, Sutter’s construction superintendent James Marshall was building a mill and deepening a millrace to run it. On January 28, 1848, Marshall walked along inspecting the work when he saw something at the bottom of a ditch. “I reached my hand down and picked it up,” he later remembered. “It made my heart thump.”

The cry “Thar’s gold at Sutter’s Mill” would go into the lore as the shout heard ‘round the world, with the belief that the world instantly rushed into the California hinterland searching for the thing that made everybody’s heart thump. In reality, Marshall never actually announced his find with such surety, and it took a bit longer for word to get out once assayers concluded that the nuggets, pea-sized bits, and flakes in the hills, streams, and rivers of California's valleys were an excellent grade of gold. Even better, it required only a bit of luck and a tolerable amount of labor to gather it up. Then the world did indeed rush in, beginning in earnest by the end of the year and producing a population flood always to be remembered as "The Forty-Niners."

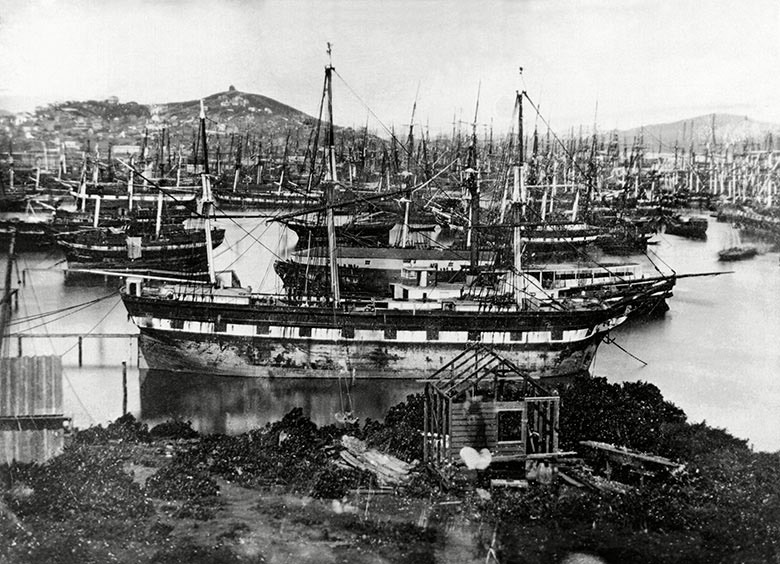

The sleepy little village by the bay was the main gateway for prospectors arriving by ship from Asia, Hawaii, South and Central America, Europe, the United States — from everywhere. Tobacco-chewing toughs who picked their teeth with Bowie knives were elbow-to-elbow with dandies in tailored suits as they came off ships that turned San Francisco Bay into a forest of masts, spars, and rigging. More than 500 vessels crowded its waters, and some of them were abandoned to rot at their moorings as their crews rushed to the gold camps. Enterprising men used winches to tug a few hulks out of the water into odorous mud where they transformed them into saloons or warehouses.

Ships abandoned in San Francisco's harbor as their crews headed inland for gold

By the summer of 1850, San Francisco had a permanent population of 30,000 people with uncountable transients coming in and out. On any given day they could swell its numbers five- or ten-fold. It made the place unrecognizable from its slumbering former self, but most of all the enormous amount of people skewed the law of supply and demand. Incredible inflation because of the gold matched significant shortages because of isolation.

In San Francisco, a single boiled egg was a bargain for a dollar, a blanket that sold for 25¢ anywhere else in the world could fetch $12 or more, and prospectors were glad to get boots barely worthy of the name for $35 a pair. In July 1850, a Boston ship brought in 147 tons of ice insulated by sawdust and sold it almost instantly at auction for more than 80¢ a pound. And as the ships brought rats from all over the world, cats meant to catch them were shipped up from Mexico to sell for $15 each. To put this in perspective, $15 in 1850 had about $450 in current spending power.

San Francisco also changed physically from beyond the water’s edge to the streets and hills. To accommodate deep-draft ships arriving by the scores, engineers built long wharves extending out on the bay. Eventually numbering twelve, these wharves were wider than city boulevards and became little cities themselves with “handcarts, porters, drays, and now and then a fine carriage” mingling with “the French monte dealer and low gamblers gathering crowds.” Women of “easy virtue” strolled the planking, aware that a woman of any kind of virtue was rarer than a Mexican cat, and could charge accordingly. One enterprising lass earned $50,000 (meaning about $1.5 million in current dollars) in 1850 alone.

San Francisco was a place almost exclusively populated by lonely men who not only slept with anyone available and at any price but slept anywhere they could, again at any price. They crammed into hotel rooms filled with a dozen or more fellow lodgers or in squalid tents full of dirty bunks and soiled cots. Little wonder that they spent most of their time at the drinking halls and gambling saloons of Portsmouth Square where gilded balusters reminded them what they were there for and larger-than-life paintings of nude women inspired them to pay for the privilege of sitting with the real thing, bosoms half-exposed and pearly teeth flashed on cue. An ounce of gold would buy an hour of conversation, as long as the patron paid for the (watered down) drinks too.

Everything about the place had at best an aura of haste barely hidden by a patina of permanence. The condition of San Francisco’s streets revealed the truth. During the rainy winter of 1849-1850, inadequate drainage flooded new structures and turned thoroughfares into channels of deep, sucking mud that could trap both man and beast. After a bad storm, corpses mingled in the soup of Montgomery Street, and other places saw sure-footed mules stumble, struggle, and suffocate. A warning posted at the corner of Clay and Kearny announced, “The street is impassable, not even jackassable.”

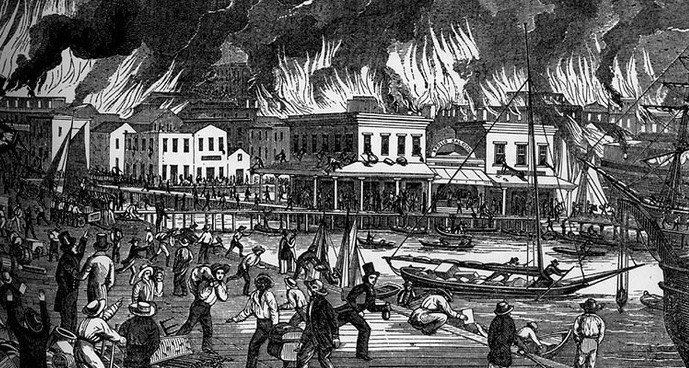

From flood to fire was but a small step. It was inevitable that such a rickety, cobbled-together, makeshift collection of shanties placed on windy hills would become worse than fire hazards. They became firestorms waiting to happen. Worse, arsonists found fires profitable because the roving gangs of “desperadoes” led by hard, scar-faced thugs like Jack Edwards could use conflagrations to loot on an industrial scale. Whether from carelessness or by the hand of incendiaries, San Francisco had six major fires between December 1849 and June 1851. The first began on Christmas Eve and set the pattern for the ones that followed in May, June, September, December, and again in May 1851, the last virtually destroying the entire city.

They could begin as small blazes in a combustible place like a greasy eatery or a paint shop, but they quickly found kindling in planked sidewalks and new pine structures with resin still sweating from unplaned boards. The fire then rapidly and horrifyingly became an inferno. A fire like that becomes something other than an elemental force: it becomes a living creature ravenous for fuel. It sends out long probing spears of flame to find it, some fifty yards long and hundreds of feet high. It generates enough heat to raise its own howling wind and thus stokes itself not merely to burn buildings but to explode them. In every instance, firemen fought best they could, and they got better at it with practice and improvements in the water supply, but the fires were not so much contained as they spent themselves, often on the waterfront. The one in 1851 was so ferocious that it didn’t stop until it ran out of city to burn.

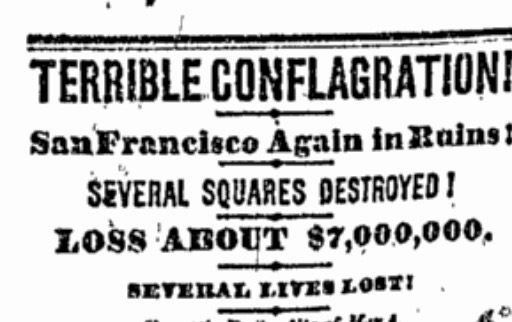

From the San Francisco Alta California

of May 15, 1851

Each fire also set the pattern in its aftermath, no matter its severity or extent. Any newspaper that survived these events was soon crowing about San Francisco’s resiliency, and with good reason. Four weeks after the Christmas Eve fire of 1849, someone landing in San Francisco would not have been able to tell it had happened. Every burnt structure had been rebuilt. Three hundred houses burned to the ground in the seven-hour fire of May 4, 1850, but half of them were replaced in only ten days following it, and construction only paused when a defective stovepipe set off the June 14 blaze and leveled several blocks on the waterfront. Likewise, structures blossomed to replace the burned ones in less than a month after the September 17 fire, and even the May 1851 event that left everyone standing speechless on the edge of a vast sea of ash did not leave these people speechless or idle for long.

More than a few observers recalled the mythical Phoenix who couldn't be permanently consumed nor at all subdued by fire but instead rose from its ashes to soar again. The heat had not yet dissipated from hissing embers before San Francisco restarted the monte games, ships again disgorged prospective prospectors, and plinking pianos unconsciously kept time to the sawing and hammering of reconstruction.

And for variety, sometimes the earth trembled just a bit. What else could one expect? The Phoenix was bound to nod at Vulcan, who was waiting to have a go at destroying this place in his own good time.

San Francisco in the years of the Phoenix was the hub of a gaudy carousel, and the prize wasn’t a brass ring but gold on the ground in nuggets. It was the place where friendly gals daubed off soot smudges from the latest fire and sat with lonely men who dreamed and dared.

“We got it all!” shouted the croupier at the rigged roulette wheel. And nobody, burning by the bay, could say he was wrong.