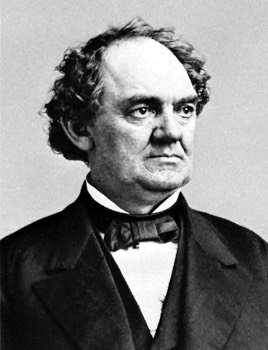

Phineas T. Barnum has returned to the limelight and boffo entertainment news these days by way of The Greatest Showman starring an exuberant Hugh Jackman showing off song-and-dance chops that many have forgotten were his early claim to fame. Something like the same thing could be said for the real Barnum. In P.T.’s pre-circus days, his fame mainly derived from running a museum that only partly depended on real and invented human oddities as attractions. Then, in 1850, Barnum pulled off one of the most extravagant, spectacular, and expensive promotions in the history of show biz. He risked everything he owned to bring a Swedish opera star to the United States for a broad-ranging concert tour. It’s worth remembering that gamble as a counterbalance to Barnum’s reputation as a mere huckster and master of hoaxes. Here was a man who could discern talent and knew how to treat the people who had it, as Jenny Lind discovered. Several years ago, we told a bit of her story, including the part about her association with the greatest showman. Given the attention being given to the talky now playing down at the picture show, we thought it appropriate to revisit it.

The master huckster Phineas T. Barnum promoted her as the greatest singer of all time, but she wasn’t. New York’s newspapers described her as a great and flawless beauty, but at almost 30 she was hardly a glowing youth and had a broad if pleasant face with ordinary features. Adoring columnists claimed she was constantly and effortlessly charming, but when tired she avoided conversation and would answer attempts at it with a mere “yes” or more often “no.” In any case, idle chatter irritated her.

And yet, Johanna Maria Lind’s American tour was an instant success before she even set foot in the country, and it became a spectacle of the first order after her first two New York concerts on September 11 and 13, 1850. The advance publicity was Barnum’s doing, but the hoopla after she arrived was simply inexplicable given her talent and looks.

She was always called “Jenny” as a child, and the diminutive stuck into adulthood. Her career, like her name, also began when she was a child because Jenny Lind was a prodigy. Born in Stockholm in 1820 to a cold woman and her meek lover, Jenny’s childhood was neither terribly horrible nor particularly happy. But she filled her hours from her earliest days with songs of all kinds both learned and made up. She hit notes well, and there was a lilting innocence along with a strangely mature timbre to her soprano that caused grownups to pause, cock heads, and frown in puzzlement before smiling in spite of themselves. One such grownup was connected enough to get her an audition at Stockholm’s Royal Dramatic Theatre, and soon she was doing bit parts in lavish productions. Jenny was ten.

She loved to sing and knew how to naturally, but her teachers focused on technique rather than ways to manage her voice, and the result was soon a sharp pain in her throat that threatened to end her career before it could begin. As it turned out, it was a warning that sadly went unheeded because her youth and a bit of rest restored her voice, at least for a time. It was long enough, though, to make her famous after she starred as Agathe in Karl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischütz. Critics were impressed, but audiences, enchanted by the 18-year-old kid who sang like a bird, dubbed her “the Swedish Nightingale.”

She soon landed a membership in the Royal Academy of Music and had become a favorite of Swedish royalty when her throat troubles returned. Overuse and bad vocal habits marred a stray note now and then during an occasional performance, but soon she was cracking into a squeak in upper octaves, and in the end, the pure notes that once had rung like a bright bell became ungainly croaks. Youth could no longer compensate. She had ruined her voice and at 20 was given up by managers and agents as well as musicians as a spent force in the world of opera. Her life was her career. Both were over.

But her optimism after a time peeked through the anguish. Jenny Lind had learned to cope as a lonely child by forcing herself to see silver linings in the darkest of clouds. It was why she traveled to Paris to seek the help of Manuel Garcia, the greatest vocal coach in Europe. At first he was too busy to trifle with a Swedish soprano who had childishly squandered her gift. Her persistence finally persuaded him to set aside a few minutes to listen to her, but only as a favor rather than an audition, and his harsh verdict was unvarnished because he wanted her to go away and do something else with herself.

Jenny Lind ruined her voice at 20, but her belief that "singing is as much moral and mental as it is mechanical" helped her recover.

The damage was irreparable, he said. He told her that she would never sing on stage again. Garcia expected tears, but to his surprise, Jenny Lind didn’t weep. She calmly asked when they could begin, and he was astonished to find himself scheduling an appointment. He had one condition. She could not sing a single note for three months. He would listen to her again after that.

She came back on the appointed day, and he listened. It was hopeless, he said. Jenny Lind calmly asked when they could begin. He paused and contemplated what he heard behind the thin tones of the young woman’s voice. He told her frankly that her genius would never again be matched by her voice. She asked when they could begin. “You must be content,” he said quietly, “with singing second to many who will not have half your talent.” She had to smile. She knew they would begin.

Ten years later she was aboard ship with a small entourage bound from Liverpool for America. She had closed out her British visit to a packed house with a lively concert arranged by Barnum as advance publicity for her arrival in New York. Behind her was an adoring Europe, wishing her well after seven years of performances in scores of operas and after her decision to retire from opera, in hundreds of concerts. Two grueling years with Garcia had returned her to the stage in a kind of magical way. She sang the works of the greatest composers, appreciative men such as Felix Mendelssohn and Robert Schumann and Hector Berlioz, all her devoted friends, and some aspiring to be her lovers. The celebrated storyteller Hans Christian Andersen was plainspoken in his love and heartbroken by her gentle rejection of it.

Barnum had invited Jenny Lind to come to America, and she had refused because she was tired of traveling and bored with performing. She knew that as she neared 30 her voice, even patched up by Garcia, was never as it had been and was now becoming more limited. Yet Barnum pulled a trick that had to make her smile. No matter what she said, he always asked when they could begin.

Phineas T. Barnum understood audiences and always treated the “talent” like royalty. Jenny Lind remembered him as a kind gentleman who made certain she was happy and comfortable.

He also granted her every request and promised such ample returns that she finally relented. She set her price high in an effort to discourage his entreaties, and he wound up mortgaging everything he owned and borrowing still more to pay her expenses and meet her fees prior to her departure for America. But the teeming crowds at the pier to greet her ship and the lines that snaked around city blocks to attend her concerts were the proof that his wager would pay off. He sold concert tickets at auction, and they often went for as high as $625, almost $15,000 in today’s money. The first two concerts in New York set the pattern for the others, and her appearances in Boston, Charleston, New Orleans, Louisville, and points in between summoned at every event hushed throngs that ended their evenings shouting themselves hoarse. P. T. Barnum and Miss Lind made a fortune.

There was the rumor eventually, and it has persisted, that they quarreled, and mainly over how much he was charging for her concerts, especially with the gaudy auctions. Barnum brought brashness to any enterprise and would have charged to see a sunset, if it weren’t already free. And while it’s true that Jenny Lind opted out of their contract before she returned to Europe and managed her remaining performances herself, stories of their relations turning sour are not supported by Lind’s letters. In them she describes Barnum as constantly kind and always eager to see that she was happy. At most, she was uncomfortable about his claims that she was an unrivaled talent and a peerless beauty. She thought the talk about talent an exaggeration and that about her looks an outright falsehood. Yet while her voice didn’t deceive many critics, people of discernment found something magical in it, as Garcia had even when it was damaged. Even more peculiar was the fact that men found her rather plain in person but were captivated by her beauty in memory. The fairy tale spinner Andersen would have understood.

Jenny Lind didn’t object about the money, for the enormous profits meant that there was more for her to give away. And give it away she did, freely and with both hands. Aside from generous donations to charitable institutions, she sent money to individuals she read or heard about, especially widows and orphans. These were unadvertised kindnesses that she meant to keep secret, and the only time that she was genuinely angry with P. T. Barnum was when he revealed her intention to make a gift of the lion’s share of her proceeds from a performance. They had a talk. He promised never to do it again.

Jenny Lind’s impulsive sense of charity might have paupered her but for a sense of responsibility to her parents and later to her husband and children. She also had people looking out for her interests, Barnum among them. And because she knew that there were good people who looked after nightingales, Jenny Lind counted herself rich beyond imagination, an accounting in her view that had nothing to do with money.

She fell in love with her accompanist on the American tour and they married just before their return to Europe. Soon they retired to England where Jenny taught voice, gave the occasional concert for a worthy cause, and raised their children. But mostly she basked. In her later years her family enjoyed holidays at a seaside resort, and one afternoon a young girl approached the great Jenny Lind as she was staring pensively at the ocean. The girl timidly struck up a conversation and finally mustered the courage to ask why Lind had given up the excitement of the stage when crowds still lined the streets to see her.

Jenny Lind smiled and tapped a book held open on her knee. The girl recognized it as the Bible. “When every day the stage made me think less of this,” said Jenny Lind, and then gazing at something behind the girl, Jenny added “and nothing at all of that.” The girl turned around and saw a riot of color smearing the clouds around a westering sun.

Phineas T. Barnum — who knew something about the relative value of a songbird, a spectacle, and a sunset — would have understood.