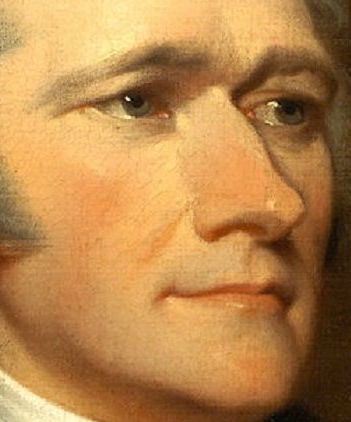

Men fell silent, and women tried to catch their breath, if he wanted them to.

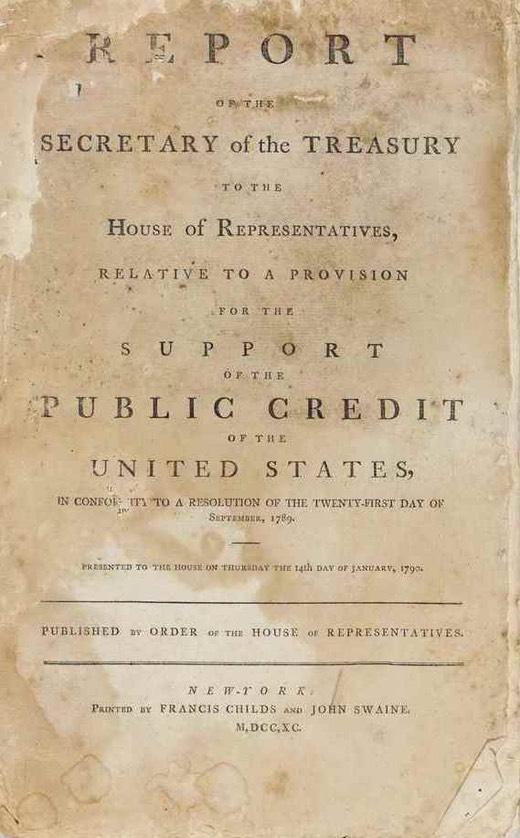

The Senate confirmed Alexander Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury on Friday, September 11, 1789, and he was at his desk the following Monday. From his very first day on the job, he displayed a superhuman capacity for work. Congress wanted a report on possible ways to address the country’s economic crisis, but nobody expected it until early the following year. After all, Hamilton had to set up his department, establish workaday routines, install the customs service, and staff everything with reliable employees. Nobody expected him to produce much more than some sketched out ideas in draft form as a starting point for discussion.

Hamilton had only a little more than a hundred days to gather a smattering of data and sketch out some barebones proposals, but a sense of urgency consumed him. He did not want to take his time because he was sure that the country was running out of it.

The economy was a wreck, and the government was broke. It confronted a dangerous combination of trickling revenue and high public debt with accumulating interest, all in arrears, the cost of fighting the Revolutionary War with IOUs to the French and the Dutch. The amounts were terrifying. The states owed a variety of creditors a total of 25 million dollars, a complex jumble in which some had been thrifty and some profligate. The country as a whole owed almost $12 million to foreigners. The central government owed its citizens a whopping $45 million. In sum, the total of over $80 million can have a modern worth at about $2 trillion in purchasing power but as much as $30 trillion in labor value. Whatever the metric, the numbers cloud the ability to grasp their enormity. The classic method of equating spending velocity to volume puts it into perspective. Spending one million dollars a day would not exhaust two trillion dollars in 5,000 years.

Such formulas are mathematical novelties, but for ordinary folk living a workaday reality, grinding debt and chronic poverty were better gauges for the problem. Paper currency at both state and national levels was so abundant as to be worthless. Parts of the country had gone without metal coins so long that seeing one became a subject of wonder, like the appearance of a comet.

Hamilton rightly judged that the economic emergency threatened to destroy America’s constitutional experiment before it could begin. So he rarely slept, always worked, and focused a mind acutely honed to the digestion, manipulation, and calculation of numbers. Hamilton also labored to look the part of a man confidently moving to sound solutions and bright tomorrows. He knew that fear verging on panic could be infectious and thus dangerous in any setting. In a martial or financial one, it was always catastrophic. So he played on his other strengths, a brash and daring demeanor that matched his towering intelligence. His physique was small, and his face had an almost feminine delicacy, but men fell silent in his presence if he wanted them to. Women tried to catch their breath, if he wanted them to.

So only a little more than three months after assuming his post, Alexander Hamilton delivered to Congress his “Report on Public Credit.” It was an astonishing piece of work. Beyond lengthy, it was epic in the reach of its data and spectacular in the scope of its solutions.

All other government business came to an immediate stop. Stunned by its length and detail, Congress at first thought Hamilton’s plan sensible and his recommendations sound. A goodly number of the members, however, did not understand the plan’s particulars as well as they should have. Others would never understand what the Report on Public Credit intended, which was more than funding the debt. Possibly George Washington was among this latter group. His lack of interest in the minutiae of the debt allowed Hamilton to work on his plan independently.

Hamilton believed that a nation’s standing with the world as well as its citizens depended less on its actual financial situation. It was more important to create the perception of financial solvency, for the reality central to all economic behavior was inescapable. Transactions involving credit result in debt. The entity owed will eventually want the money, “eventually” being the operative word.

Fostering the belief that a debtor could meet obligations was more advantageous than keeping a tidy ledger with neatly balanced columns of assets and liabilities. It established the debtor’s ability to borrow additional money in the future. In short, paying off debt was important, but having a convincing plan to pay off debt provided nearly limitless options and opportunities. Raising taxes to retire obligations more quickly might seem virtuous, but it was counterproductive. High taxes would cripple the economy and impede its ability to pay off more than a portion of its bills. The trick was to encourage confidence that the debt would indeed be paid down, and eventually off, no matter what otherwise happened.

Hamilton meant to achieve the trick with a complex web of funding that would span decades. Accepting this lengthy schedule required a novel interpretation of debt as a tool rather than a burden. Hamilton posited that debt in itself was not a problem. Creditors, and more precisely, the wrong kind of creditors, posed the real predicament. Liability in the right hands — say, America’s wealthiest class — would give the right people a material stake in the country’s survival. They would be compelled to act in the country’s interest out of self-interest. It would be the neatest trick of all. Hamilton’s policy did not expect good people to do the right thing. It made doing the right thing worthwhile for everybody, whether they were good or bad or indifferent.

Convinced of his good idea, he proposed an additional and even more radical solution. Hamilton planned to have the national government assume the burden of the $25 million worth of obligations that the states had incurred during the Revolutionary War. The mechanics of this were formidable, and the costs were staggering, but Hamilton insisted that it was the surest way to secure the confidence of potential investors both at home and abroad. The message would be that the country was open for business and a zero risk for lenders. That kind of credit meant unleashing enormous power and harnessing prodigious purpose.

The promise of economic recovery, boosted prosperity, and financial stability could have been irresistible, but the details of the plan and its potential consequences gave sagacious critics pause. It was sure to grow the government, and it featured ways to make the government active and intrusive. The Treasury Department already was on track to become the largest and most important part of the executive branch and, more worrisome, the most ubiquitous government presence in American life. Collecting revenue through import duties and sumptuary taxes required a sizable bureaucracy with hundreds of customs officials, lighthouse keepers, and revenue agents all over the country. Hamilton’s reach would beggar description. It would stretch from the piney woods of the Maine District to the pine barrens of the Georgia frontier. It would rival and possibly even surpass that of President George Washington.

The prospect was troubling enough, but doubly so because Alexander Hamilton was troubling. He had been born in the British West Indies in either 1755 or 1757 (Hamilton muddled the dates), the illegitimate child of a Scottish father and French Huguenot mother. The confused paternity was more than embarrassing — John Adams would famously scorn Hamilton for being “a bastard brat of a Scotch peddler” — because the stigma of illegitimacy drove Hamilton’s ambition and inclined him to brood. Hamilton’s genius was evident to anyone who met him, but less apparent was how he suffered from somber dissatisfaction. Hamilton could tarnish achievements with impulsive bursts of unhealthy introspection. The West Indies of his youth became for him a metaphor of the larger world, a beautiful place blighted by slavery in its cruelest form. It prompted Hamilton to believe that all metals were alloyed, all people flawed, and all things lovely were likely incubating disease. He doubted that virtue existed outside of fables. He could be needlessly nasty in political disagreements.

He married into an elegant New York family and thereby achieved status in America’s aristocracy, but it was not enough. He loved Betsy Schuyler, but fragile fidelity marred their marriage without her even knowing it, at least for a time. There was at least one other woman, and likely more, as something other than sexual desire drove him to affairs. Private happiness and professional success were never enough for a man who could not shake dark thoughts nor turn away from dire predictions. Astute observers suspected the brash confidence was a front and the sunny optimism an act. Alexander Hamilton never thought of American citizens as intuitively intelligent about money, liberty, or order. As far as he could see, they spent too much, confused freedom with license, and tended to fly into rages over trivial irritations. Their instincts were seldom sound, and their passions were rarely restrained. People like that had to be herded and controlled.

He seldom talked about this so explicitly, and describing it this bluntly simplifies the complexity of a man who often mystified even his supporters. “I am a stranger in this country,” Hamilton once confided, revealing an innate talent for self-awareness. When the country gave him the keys to its Treasury and the powers to save it, he invented an imaginative financial program that only a few would understand and some would hate. In that, Alexander Hamilton and his plan became as one, an indistinguishable whole, sublime while cursed, a road to salvation across a beastly landscape. The country still argues about it, and him.