Among the many unlucky things that happened to Millard Fillmore, possibly the worst was becoming president of the United States. It happened on July 9, 1850, and if you missed the 165th anniversary this past Thursday, you weren’t alone. Many of the “Today in History” lists refrained from mentioning Fillmore’s becoming president, underscoring the judgment of historians that he belongs in the lowest of presidential rankings. When he is worthy of notice, it is always disdainful, which was the case among cynical people then and has been among scholarly types since. About the time young Fillmore was getting started in politics, John Jacob Astor is said to have told him that he was a nobody from nowhere going nowhere fast. It was true as far as crude fur trading moguls and sniffing scholars go, because poor Fillmore was always an easy target. Meanwhile if Americans now know his name at all, it’s as a cheap play on words. The eponymous comic strip that features a duck named “Mallard Fillmore” is always good for a laugh.

Yet the laughs come at a good man’s expense. Millard Fillmore became president when the United States was facing the most serious existential crisis in its history, the one that foreshadowed the secession winter of 1860-61 as a prelude to the Civil War. Few thought he was up to the challenge, and they remained convinced of that even after a rather surprising performance. It is curious that people did not change their opinions about Fillmore even after he held his administration together with firm resolve and a calm demeanor, quelled internal menaces while salving the wounded pride of disaffected citizens, and initiated a foreign policy that blunted European aggression and opened xenophobic Japan to American diplomatic and commercial relations. He signed legislation that ended the threat to the Union, even when he knew that at least one part of the Compromise of 1850 would destroy his political career and tarnish his reputation. He regarded his political career of slight importance in the balance of the country’s best interests.

A man like that would seem worth knowing and certainly worth remembering, especially since his origins were humble and his life was hard from the start: born in a log cabin, oldest son of a large family, he helped to work a marginal farm in upstate New York as he watched his father teeter on the edge of abject poverty. When he reached his teens, Millard tried to make his way far from home as an apprentice to a cloth maker, an honest trade that might have been his way in life, but his master was unpleasant when not abusive. Millard bundled up his meager possessions to walk the 100 miles back to his family. He was 14. He tried another cloth-making apprenticeship but eventually realized that the work might make him a living but never provide him a life. He was one of those American youngsters like Abraham Lincoln who yearned for something, and not necessarily something more but something better.

During breaks from the cloth-cutting table, Fillmore sharpened his rudimentary reading skills by poring over every book he could find, sounding out the words and writing down the many he didn’t understand to look up later. The lad’s diligence paid off to land him a couple of jobs teaching grammar school, which meant he mainly monitored rote recitations, but it was a life of the mind, after a fashion. When a local attorney gave him a chance to do some clerking, Fillmore’s course was finally set. He met a pretty girl at a school he briefly attended in 1819, and while Abigail Powers saw potential in him, he saw the moon and the stars in her.

The way he acted toward Abigail provides a window on Millard Fillmore’s heart and mind. Though head over heels, he would not be imprudent because he had known poverty and wouldn't have Abigail live in it. He was admitted to the bar in 1823 but worked three years to establish a practice before asking Abigail to marry him. It was an an absurdly long courtship, but she doesn’t seem to have doubted from the day they met that she would marry this good man who never said anything he didn’t mean, never made a promise he wouldn’t keep, and never bought anything he couldn’t afford.

These admirable habits made Fillmore a stolid citizen, a reliable husband, and a provident father, but it made him a plodder in politics. Beginning in 1829, he served three one-year terms in the New York legislature, but nobody would have called his service spectacular, and that was fine by him. He drafted a law to end imprisonment for bankruptcy, and he was able to get it passed only by letting his opponents in the Democrat Party take credit for it, which he didn’t mind. Just as he was willing to defer the gratification of marrying Abigail until he could provide for her, he was willing to stand in the shadows and assume the role of plodder to achieve a good objective. A decade later, he behaved this way in the House of Representatives when he was chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, which meant that his political reputation was lusterless and ordinary. Voters in New York didn’t think he was worthy of the governorship when he ran for it in 1844. He might have agreed with them.

Fillmore’s first name strikes modern ears as comical, but it shouldn’t. “Millard" was his mother’s maiden name, and it was customary to settle it on a family’s oldest son as a mark of respect for her family.

It shouldn't surprise then that Fillmore never wanted to be president. Cynical handlers made him Zachary Taylor’s running mate on the 1848 Whig ticket because he was from New York and could balance Taylor’s being from Louisiana. Just as important, Fillmore could furnish the ticket with some measure of ideological meaning, since Taylor didn’t have any political opinions about anything except wanting to be president. Actually, Taylor’s qualifications for the presidency rested exclusively on his reputation as a military hero from the recent war with Mexico, which is to say he had no demonstrable qualifications for the office at all. Worse, northerners were apt to identify him with proslavery sectionalism, mistakenly as it turned out, but that was because nobody knew what Taylor believed about anything during the 1848 election. It was not the first, nor would it be the last time that the people who run political campaigns counted this as a positive.

On the other hand, Fillmore was quite well known as a plodding, moderate northern Whig committed to antislavery, a position that was indistinguishable from that of other moderate northern Whigs, Abraham Lincoln among them. Fillmore was young — 48 when he was nominated — and had better political connections and more legislative experience than many of his contemporaries, but best of all he wasn’t likely to upset anyone. Whigs and Democrats knew him for his honesty in public service and his candor in private relations, but that didn’t impress the diamond-eyed political professionals who brokered deals and broke down careers in smoky backrooms and dimly lit public houses. They could portray Zachary Taylor as a hero and forget about old reliable Millard, even though he was the better man.

There was an inkling of that depth to Millard Fillmore by the summer of 1850 when the country was in a great deal of trouble. Congress had been viciously debating the fate of slavery in western territories acquired from the war with Mexico, and Fillmore as vice president was presiding over the most contentious Senate in anyone’s memory. As debates became ugly and members boasted of packing pistols, Fillmore strode into the chamber on April 3, 1850, and brought his gavel down hard enough to bring a murmuring silence to the unruly assemblage. He calmly but sternly announced that he was henceforth ending the tradition of the vice president as merely a titular figurehead in his role as presiding officer. Rather, he would enforce parliamentary discipline, maintain strict rules of order, and punish disruptive behavior. Many in the chamber listened to this announcement in stunned silence and looked at Millard Fillmore as if they had never seen him before, but nobody could blame them. New York senator William Seward, a rival, had been treating Fillmore with scorn, and President Taylor had not only ignored Fillmore but had pointedly refused his modest requests for a small say in the selection of appointments within the administration. In fact, Taylor had taken the advice of his vice president’s enemies to choose anti-Fillmore Whigs for even the lowliest offices.

It revealed a mulish streak in the president that was mirrored by his handling of the crises engulfing the country in 1850. Rather than work with leaders of his own party in Congress to advance a compromise solution for the overheated sectionalism threatening the Union, Taylor rebuffed those leaders and gruffly resolved to call the South’s bluff. Millard Fillmore had seen the debates in the Senate. He knew the South wasn’t bluffing.

And that was the situation when events vaulted Fillmore into the presidency. Taylor took part in Fourth of July observances under a blistering sun and afterward tried to refresh himself with cold milk and a bowl of iced fruit (cherries, by some accounts), making himself sick enough for physicians to kill him with cures. When Fillmore was sworn in, wags were already calling him “His Accidency,” and the professional cynics in both parties were confident his tenure would be a catastrophe.

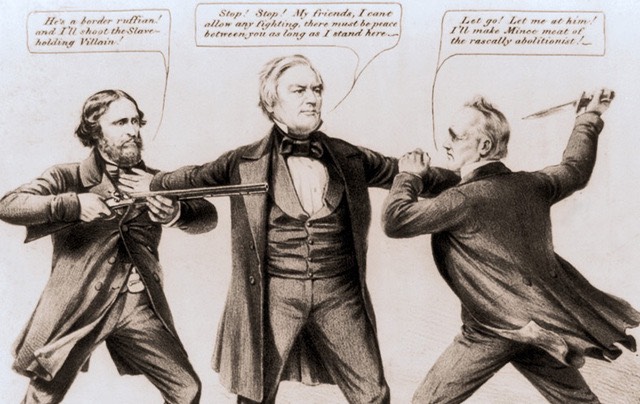

Some Americans realized the impossible situation that President Fillmore was in during the 1850 sectional crisis, and this cartoon depicted him as a resolute referee standing between irreconcilable radicals.

But Fillmore helped to save the Union by encouraging the compromise that calmed the crises of 1850, and he thereby averted the same sort of breakpoint that would imperil the country a scant ten years later. He signed a bill admitting California to the Union as a free state, another abolishing the slave trade in the District of Columbia, another organizing the southwestern territories on the basis of popular sovereignty, and still another that settled a volatile border dispute between Texas and the New Mexico Territory. And yet he also had to sign a repugnant Fugitive Slave Bill into law to soothe southerners who correctly assessed the bulk of the Compromise of 1850 as injurious to their interests. The Fugitive Slave Law was as distasteful to Fillmore as it was damaging to his standing at the time and his reputation ever afterward. But for him his career and his reputation were of slight importance in the balance of his country’s best interests. In that he was a rare public servant, let alone a rarity in the presidency: Millard Fillmore never sought credit but was always willing to take the blame.

He never claimed to be a great man, and his fellow Americans never mistook him for one. As president, he was characteristically self-effacing and never stood on ceremony or invoked protocol beyond the necessities of preserving the dignity of the office. When he left that office, he cast off even the most minor perquisites of it. Oxford University sought to award him an honorary degree, but Fillmore declined by claiming himself unworthy for many reasons, not the least of which was his ignorance of Latin. He could not in good conscience, he said, accept a diploma he could not read.

Fillmore was in the final year of his presidency when Henry Clay was dying of tuberculosis in the National Hotel. The great tumult of 1850 had receded, and the country was at peace for the time being and strong abroad, both thanks to Fillmore’s customary willingness to stand back and give others credit for work he had toiled over. One afternoon he left the White House without any companions for a walk to the National Hotel. There he visited Clay for a lengthy spell in his room. As Fillmore rose to leave, he quietly asked if he could visit again, perhaps to bring his sister, but only if they would not be imposing on Clay’s hospitality. Fillmore smiled and said that it would be a treat for his sister to meet a truly great man.

For once in his life, Millard Fillmore had not quite told the truth. By then, Clay looked wretched and was an unnerving wraith, barely able to talk, and likely to frighten visitors rather than inspire them. Yet Fillmore summoned the scenes of Clay’s former glory as effortlessly as he discounted his own importance as president of the United States. He was worried that this old man, far from home and fatally ill, was lonely. It was the gesture of a good man, which Millard Fillmore was, when his country needed one.