In September 182 years ago, Sam Houston became President of the Republic of Texas. One hundred and seventy years earlier, the most popular song in the English language was making its mark in London’s entertainment world. If you don’t see the connection, stay tuned.

First a bit about the man. Many Americans know about Houston’s role in the fight for Texas independence. His life before that isn’t so well remembered, in part because he wanted it that way.

Before Sam Houston showed up in Texas, he had already achieved fame on an ever upward arc of success, until everything went wrong. As a youthful army officer, he had almost gotten himself killed during the Creek War in 1814. But his valor caught the attention of General Andrew Jackson, who made the lad his protégé. Under Old Hickory’s watchful eyes, Houston prospered. He joined the powerful Nashville Junto that directed Andrew Jackson’s political career to make him first a U.S. Senator and then the President of the United States. Jackson’s rising tide raised Houston’s boat as well. In the 1820s he sailed to a seat in Congress before landing as Tennessee’s governor. His political talent assured even smoother sailing to even greater ports of call.

Then, as he prepared to run for a second term as governor, he got married. And we’ll ask you to hold that thought while we explain the song.

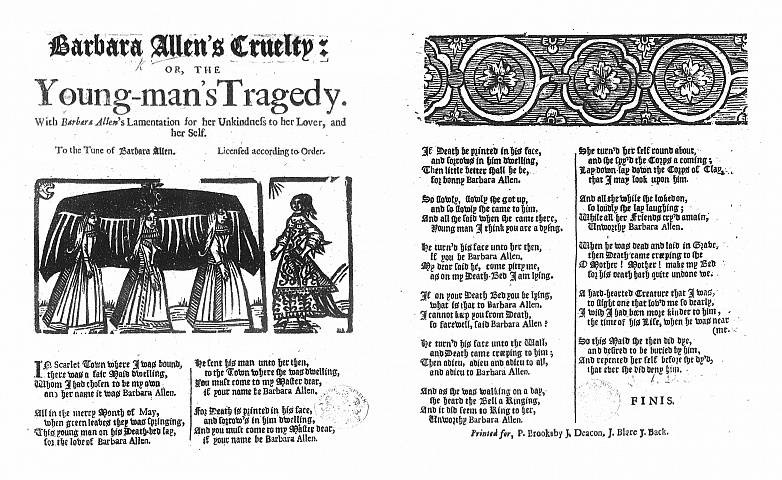

In 1660, the English diarist Samuel Pepys heard a plaintive Scottish ditty at a New Year’s party. Pepys recalled it as “Barbry Allen,” but “Barbara Allen” was the more refined version. Whatever its title, it was a first-class, solid-gold hit that was taking stage, street corner, and saloon by storm. It was no flash in the poetic pan either. “Barbara Allen” has never faded in popularity over the three and a half centuries since it began misting up the eyes of jilted lovers and making old folks pensive. It is a timeless story set to a haunting melody that defies classification and transcends place.

Its longevity meant the song was bound to evolve into various versions, but in none of them does the eponymous Miss Allen come off very well, and her end is always tragic. The earliest of the verses tells the story of a bonnie if rather grim lass called to the deathbed of a lad she secretly loves. Yet she cannot let go of her wounded pride. He once toasted the health of everyone in a local tavern without mentioning her. It suggests a petty streak, and her greeting in the sickroom is not promising: “Young man, I think you’re dying.” She coldly listens to his confession of love, and she foolishly leaves him unrequited. The lad is crushed but forgiving: “Adieu, adieu, my dear friends all, and be kind to Barbara Allen.”

The dear friends never have the chance to test their magnanimity. As Barbara Allen walks, the church bells peal his death knell; she is at last shaken to her senses. Arriving home, she tells her mother to prepare her bed. “Since my love died for me today," she says, "I'll die for him tomorrow.”

The story is more than simple. It’s elemental in laying bare the human condition of pride, love, and loss. Yet would that life were so straightforward. If pride, love, and loss were that direct in moving actual events and changing real lives, we’d all be wise and seldom sad. Keep that in mind while we consider the story of a blue-eyed, ashen-curled American Allen. Hers is a contradictory case in point.

Our Miss Allen was the daughter of a prosperous Tennessee planter. She was a sprightly child named not “Barbara” but Eliza. She grew into her teens and filled out fashionable gowns with scores of suitors drawn by her beauty and encouraged by her father’s wealth. But one was unexpected and odd. Though he was a friend of the family, he was hardly the boy next door. For years Sam Houston had been visiting the grand house named Allenwood, at first as an honored guest holding important political office. He watched Eliza Allen grow up, and once she hit eighteen he became a smitten man paying court to a vivacious teenager. So the story goes.

His friends believed that Eliza Allen had bewitched Sam Houston, but in a wistful, charming way. Her transformation and his reaction to it resembled a fairy tale, even if Prince Charming was a bit long in the tooth. One day, perhaps, he saw her descending a staircase or entering a room and was shocked that yesterday’s child had become a dazzling beauty. In movies it's always the plain girl taking off her glasses and undoing her hair that causes the previously indifferent chap to purr, “Why, Miss Jones.” The soundtrack swells, and you know the rest.

But you also know that life is never like a storybook or a movie. In life, chapters don’t span symmetrical events, and scenes don’t dissolve into the next plot turn. Most of all, life is not at all like a song. Even if what happened to Sam and Eliza made inebriated romantics warble “Barbara Allen” in countless American taverns, the two were not an instance of life imitating art.

The cold facts of their courtship highlight the fact that there wasn’t one. There were no longing gazes on lazy afternoons or innocent intimacies shared under arbors, no hands held, no lips just brushing, no knowing smiles traded across crowded rooms. There was instead an arrangement between Sam Houston and Eliza’s father John Allen. Sam was pushing 40 and in a difficult reelection campaign that a respectable bride and a political ornament would help. Allen was an influential citizen more than willing to advance his family’s fortunes. Forging a family connection to Sam Houston presented a lovely prospect. He was governor and would likely be more, given that his mentor Andrew Jackson had just been elected to the presidency. It was sensible to dress up the alliance as matrimony.

Sam Houston as he started his “second life” in Texas. There are no portraits of Eliza Allen. She reportedly had all likenesses destroyed, as if she never wanted to be remembered.

Sensible, except to Eliza Allen. Nobody to this day knows where she figured in these calculations. Barely emerged from her childhood, what did she want? Speculation about the answer to that question was soon rampant because of what happened to the “happy couple” after they were married on January 22, 1829. A bundle of anecdotes from Houston’s admirers painted Eliza Allen as cold, heartless, and calculating, an American version of the Scottish Barbara. But a heap of stories from Eliza’s defenders portrayed her as wronged, violated, and abused, a fate far worse than getting left out of a toast.

All that aside, nothing contradicts the stark fact that her family wanted her to marry Governor Houston. Circumstantial evidence suggests that she consented to an arrangement. Sam Houston seems to have taken the matter rather more seriously.

The night of their wedding ceremony was a promising start. It sparkled with elegantly attired neighbors flocking to Allenwood to see the governor take his bride. She was a vision in white silk and satin roses. A grand banquet and hearty toasts made for a long celebration, and not until the wee hours did Sam and Eliza retire to their bedchamber. Then, in the few hours before dawn, everything went wrong.

In fact, something awful happened in that room that night. Only Sam and Eliza knew what it was, but everyone else can surmise that it had to be awful. It marred the Houston marriage so irreparably that it lasted only twelve weeks. Even more, the union ended in a way that encouraged vivid imaginations to conjure up causes. They always begin with that first night in the bedchamber at Allenwood. Versions ranged from the lurid to the pathetic. The lurid version painted an innocent child roughly handled by an overeager man-of-the-world. The pathetic version imagined that Houston’s war wounds repelled Eliza. One in his groin had never healed and — the word most used: “oozed.” Finally a romantic version had Eliza regretful over forsaking her true love. He was himself a tragic figure dying of tuberculosis, it was said.

Whatever happened, Eliza was unhappy the day after her wedding. One account has her terrifyingly miserable with a sinister twist. Heavy snowfalls delayed the grim wedding trip to Nashville at points, and the couple stayed at a plantation named Locust Grove. Friends noticed Eliza's face was like marble set in an expression of profound grief. Houston romped in the snow with children on the front lawn, and the mistress of the house playfully suggested that Eliza help her husband in the snowball fight lest he lose. The woman later recalled that Eliza muttered, “I wish they would kill him.”

That was what Eliza’s hostess later recalled, and maybe it is true. It’s difficult to imagine someone of Eliza Allen’s upbringing and intelligence saying something like that to a friend, let alone an acquaintance. In any case, the couple’s impossible situation did not improve when they reached Nashville. They moved into rooms on the second floor of the Nashville Inn, but it was hardly a home. Eliza’s defenders later claimed that Houston was so possessive that he would not allow her the freedom of little shopping trips or visits to friends. Perhaps that is true, as well. But other reports tell of Eliza moving unencumbered about the town as the state’s First Lady.

Public perceptions in retrospect are open to dispute. They seek to explain what happened while defending one or the other of the couple. There can be no doubt, though, that Eliza’s coldness raised Houston’s suspicions. Evidence points to another dreadful night when something awful happened between them. Unlike their wedding night three months earlier, the events of April 8, 1829, are clear. While Houston was away on a campaign trip, she left for Allenwood.

Stunned by her departure, Houston that morning wrote an extraordinary letter to Eliza’s father. “The most unpleasant & unhappy circumstance has just taken place in the family,” he opened in what became a treatise of euphemisms. He went on to say: “Whatever had been my feelings or opinions in relation to Eliza at one time, I have been satisfied & it is now unfit that anything should be averted to.” He stumbled on this way at length. John Allen never answered him.

As tongues began to wag, Houston could not bear the humiliation. Within days he abandoned his reelection bid and resigned the governorship. After a few more days of heavy drinking and sequestration in the Nashville Inn, he slunk down to the landing on the Cumberland River and boarded a steamboat to take him west. Houston’s friends worried that he would kill himself.

By then, the Allens were angry. Gossip about the reason for the separation enraged them. For his part, Houston didn’t help by talking indiscreetly while in his cups. As he traveled the river with curious companions, he was feeling sorry for himself, and he filled late nights with boozy lamentations. The subject is not hard to guess. One of those traveling companions wrote letters bemoaning how the country was being deprived of Sam Houston’s indispensable service because of “the dishonor and baseness of a woman.”

Such stories prompted the Allens to take extraordinary measures of their own. They arranged for Eliza’s vindication by a committee of distinguished Tennesseans. The committee's investigation exonerated Eliza’s character, and its published report created a sensation. It included Houston’s rambling letter to John Allen. When newspapers throughout the country reprinted the story, it helped to ruin what was left of Sam Houston’s political career. It also shattered the few remaining shards of his social status, many thought forever.

The Scottish Allen of song had an easier time than the American one of real life. Barbara Allen took to her bed, died, and ended her story with a tragic flourish as her sad melody faded to silence. Eliza Allen didn’t die. There wouldn't even be a dramatic conclusion to her story. For years she remained at Allenwood in Tennessee. She also remained Mrs. Houston, despite her husband’s departure for the west where he took a common law wife among the Cherokee and later fetched up in Texas.

Eliza followed the exploits that made her husband the first President of the Republic of Texas. She rarely spoke of him, and only once or twice was it with a hint of harshness. Out in Texas, President Houston at last divorced Eliza in friendly courts staffed by his own appointees. It was eight years since she had left the Nashville Inn and her husband. He had been first suspicious and then tearful, and in his own way had been dying inside. Yet there was never a death knell to free Eliza Allen. Instead, after eight years the mail brought her the news that she had been cast off.

Sam Houston married again, but the woman in Tennessee, now approaching thirty, remained by her own choice Eliza Allen Houston. Perhaps it was a sort of penance for her weakness when she married a man she did not love because her family wanted her to. It was also a rebuke to that family for what it had asked of a girl who had spun away the best years of her life because of a twelve-week mistake. In the quiet halls of her father’s house, she was neither a spinster nor a bride. The woman who was never a wife was still in the end a divorcée.

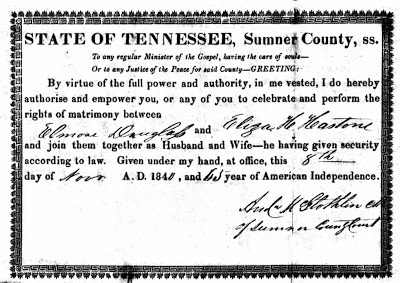

The music should fade here, of course, and the song end with a sad lyric about pride, love, and loss. But the American Allen was not a creature of song. The blue-eyed Tennessee girl with the ashen curls refused the role of a wasted woman with a loveless life. She was quiet and patient, and finally someone saw her descend a staircase one afternoon, or perhaps simply walk into a room one evening, and was stunned by the sight. Eliza Allen Houston married Elmore Douglass in November 1841. There would be children.

So in her song the American Allen does come off pretty well after all.

Cue the music.