Everyone knows the song that begins:

In 1814 we took a little trip

Along with Colonel Jackson down the mighty Mississipp

James Morris wrote it, and Johnny Horton made it famous as a recollection of the Battle of New Orleans that is exuberant if inaccurate in many details. Horton even recorded a version for release in the United Kingdom that has the British winning, so precise historical fidelity was never high on the priority list for hitmakers.

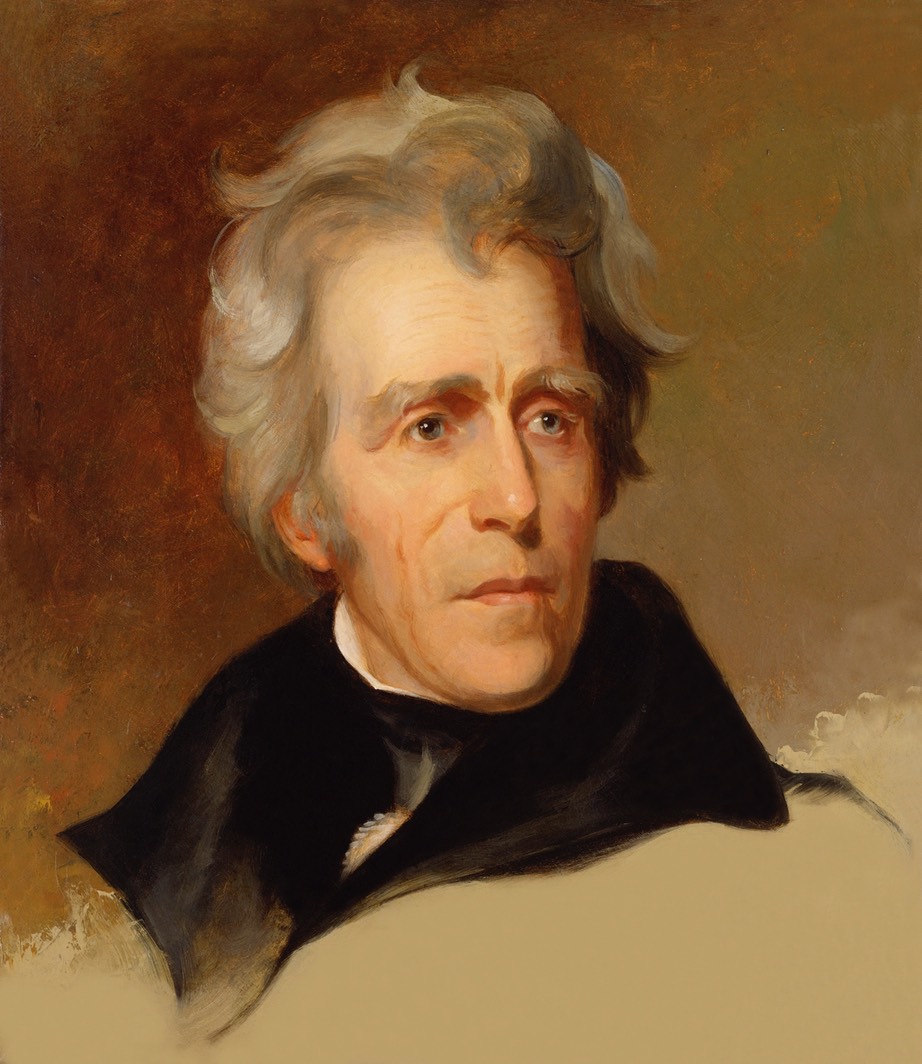

The person at the center of the song is Andrew Jackson, who wasn’t a colonel but a general. Today, March 15, is his birthday, and this year he would have been 249 years old. For many of those who knew him — whether in love or to hate— they were likely surprised that he could ever die, suggesting that two and a half centuries (and counting) were entirely possible for a man too beloved to pass or too mean to expire, depending on one’s point of view. In case you missed the furor, Jackson of late has been a target of scorn, mainly because of his central role in fighting southeastern Indians and then promoting their forced removal to regions west of the Mississippi River. It is surely a disgraceful legacy, but whether it merits the airbrushing of Andrew Jackson from recollections of the American past is less certain.

A few years back we took a look at one of Jackson’s more controversial exploits in our book about the First Seminole War of 1818. Oddly enough, it was a war that had less to do with Indians and almost wholly concentrated on accosting Spaniards in Florida, which they then owned, with the goal of expelling them for American expansion. No, the actual Indian- fighting days of Andrew Jackson occurred some five years earlier during the War of 1812, when he destroyed the Red Sticks during the Creek War. This was before his “little trip” to New Orleans (which was overland rather than down the Mighty Mississipp), but in many ways it defined him for his neighbors just as thoroughly as his triumph at the Crescent City in January 1815 did for the nation. The airbrushes are put away in what follows, to avoid both the giddy lionization of Andrew Jackson and the equally deplorable sin of forgetting him altogether. He was more complicated than both his admirers and his detractors would have us believe. The passage is from Old Hickory’s War: Andrew Jackson and the Quest for Empire and has been adapted for this post.

During the Creek Indian War of 1813-14, Andrew Jackson gained the reputation of a hard-bitten Indian-hater. Many of his contemporaries saw nothing wrong with that, but many historians have, with the result that debates have raged over Jackson’s actual attitude toward Indians ever since.

Some have argued that Jackson hated the British for making Indians their pawns. In this view Jackson took action against Indians to vanquish their British manipulators and achieve American security. Others, however, think that Jackson’s violent frontier days in early Tennessee planted in him a rigid opinion of Indians as savage and untrustworthy. “Why do we attempt,” Jackson wrote in 1793, “to Treat with Savage Tribe[s] that will neither adhere to Treaties, nor the law of Nations.”

He still felt that way in 1813 when he led the Tennessee militia against the nativist Creek Indians called Red Sticks. By then Jackson was forty-six years old, propertied and prominent. He owned a large estate near Nashville and had won eminence in political and legal venues. Yet, mature deliberation and rational thought were always brittle facets of this man’s turbulent personality. His marriage to already married Rachel Donelson Robards provided grist for scandal mills most of his adult life, and Jackson reacted to the gossip with gestures that were sometimes wild and often undignified. When Governor John Sevier suggested impropriety in Jackson’s courtship of Rachel, Jackson tried to force the governor to fight a duel. Charles Dickinson, a young Nashville attorney, reportedly maligned Rachel’s virtue. Dickinson claimed he was drunk, had meant no harm, and apologized; nevertheless, he and Jackson continued to quarrel over other matters until Jackson shot Dickinson dead in a duel. Of course, such actions only muted sniggering talk about Rachel while spreading it farther. Worse, it created the impression that Andrew Jackson was uncouth at best. His harshest critics bluntly called him a murderous bully.

Jackson took a bullet in his chest in the Dickinson duel. The wound would plague him for the rest of his life, but it was only one of a growing list of physical injuries to match his spiritual scars. His involvement in politics saw him using intimidation almost as often as persuasion, and he made enemies by the scores. He made certain that they knew where they stood with him and what fate awaited them should they risk a chance encounter. At the core of him, then, was an apparent believe that he was a law unto himself. It made him willing to engage in questionable enterprises if they promised to advance a program of which he personally approved.

That sort of certainty had Jackson moving as a tempest, a force capable of killing everything but vile talk and vicious rumors. It was, after all, sprinkled with fine, ghastly grains of truth. In spite of defenses mounted by admirers then and since, nothing can alter the evidence that Andrew Jackson was an angry young man who became an angry old man. As some have suggested, perhaps he contrived for effect some of the rage that peppered his life, but quieter tantrums sprang from his insides and sculpted his character. His mother had died of cholera during the American Revolution, making young Andy an orphan at fourteen. As far as he could reckon, the British had done that, had created the hardships of pestilence and destruction that killed his mother, his brothers, and the gentler edges of his nature. He detested swaggering Spaniards just as much: they held Florida, and he was certain they encouraged Indians to attack the American frontier. He brooded over their contempt for the United States and resolved to destroy them and any of their friends. He would take their land, dash the standards of His Most Catholic Majesty to the ground, crush the British Lion and Unicorn. He would stand before their Indian allies as he had before young Dickinson, even after taking the bullet, his absurdly narrow shoulders drawn back, his long head tilted down to stress the snarl and shade his blue eyes from the sun. He would carefully draw aim. He would kill them all.

At Tohopeka, the Horseshoe on the Tallapoosa River, Andrew Jackson nearly killed them all. It was in March 1814, and one thousand Red Stick Creeks were camped there, taking false comfort in the protection the curving river gave their backs and placing mistaken faith in the elaborate breastworks they had put up in their front. Jackson immediately saw that Horseshoe Bend was more a fence than a shield. The Red Sticks had put themselves in a corral that on March 27 Jackson turned into a slaughter pen.

A Diorama at Horseshoe Bend National Military Park

His artillery opened on the Red Stick front while men he had sent across the Tallapoosa waited to kill any Indian who tried to flee by swimming the river. After a five-hour battle, 557 Creeks lay dead on the land in the bend with as many as 300 bobbing lifelessly in the Tallapoosa. Jackson’s militia and their Indian allies continued the killing until dark stopped them, but they renewed what amounted to systematic executions the following morning. The high toll of Horseshoe Bend concluded the Creek War. Jackson had killed over 800 Red Stick warriors.

It was less than two weeks after his 47th birthday, and in some minds, the victory might have seemed like a belated gift, but he wouldn't have agreed. Jackson always killed for a purpose, and the complexity of his character is encompassed by his raging over things that didn’t matter (like politics) and adopting a cold calculation about matters of life and death. By the time he came to Horseshoe Bend, Jackson’s soldiers had already dubbed him “Old Hickory” for his superhuman physical perseverance that put them in mind of the hardwood that would neither bend nor break. After Horseshoe Bend, the Indians called him “Sharp Knife.” The name suited him, and the givers of it were noted for penetrating insight in matters of nomenclature, especially with enemies. “Sharp Knife” suited him. He doubtless liked it.