Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner had been working on “the speech” for weeks, carefully revising it and practicing his delivery in front of a mirror in his boarding house. It was said that he kept fellow lodgers awake throughout the night, ignoring their complaints and continuing to declaim while eerily illuminated by a candle held by “a Negro boy” Sumner had hired to watch his gestures. Everyone was already on edge when Sumner stood in the Senate on May 19 to begin an address that would span two days. It was five years before the Civil War, and the events about to happen would be among the final mileposts on the road to it.

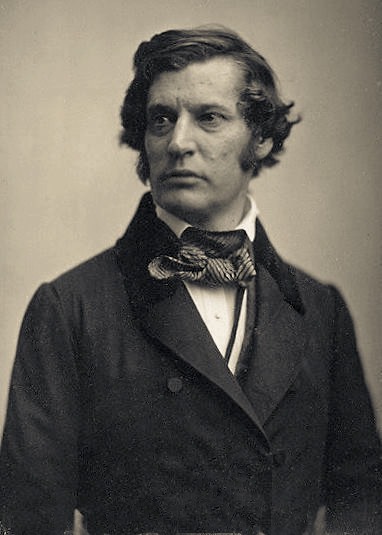

Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner looked like a statesman, and for many northerners he exemplified American virtue in his ability to distill slavery to its horrid reality. Sumner did not employ subtle euphemisms but exuded a moral certitude that in a lesser man would have resembled preening. Yet Sumner was quick to blame transgressors. He never followed the charitable instruction to condemn the sin but forgive the sinner, the habit of Abraham Lincoln, who didn’t look at all like a statesman but behaved like one.

Sumner wasn’t on speaking terms with any southern Senators and was regarded warily by many northern ones. His way of reversing the normal behavior for private and public life was the reason. His public face was one of imperious dogmatism and a drearily superior attitude. His private one was benign and generous. Those who encountered Charles Sumner at dinner parties and drawing room sociables met a considerate man who was solicitous and kind. In later years, Mary Lincoln, who reflexively despised radicals of Sumner’s stripe, adored him.

Yet as much as he was admired outside the Senate, he was in various measures of intensity detested in it. Something beyond his opinions and haughty manner caused this. The most contradictory facet of Charles Sumner’s public face was that of a highly educated lout with no sense of appropriate behavior. He was a talented orator classically prepared and armed with the wisdom of the ages, but he resorted to cringe-worthy vulgarisms. Those who knew the two faces of Senator Sumner were always brought up short by the ugly one. Like a beautiful woman whose odor betrayed bad hygiene and whose smile revealed rotting teeth, Charles Sumner was an altogether unpleasant incongruity, a kind man who found it easy to be cruel, an erudite scholar who enjoyed being crude.

His speech on May 19, 1856, was, in that respect, a masterpiece in the Sumner repertory. He later gave it a title — “The Crime Against Kansas” — and he touted it at the time as offering “the true remedy” for the mess in the Kansas Territory that had the forces of freedom and slavery fighting over the land and its future. Yet Sumner’s actual purpose was to provoke rather than persuade. He singled out Illinois senator Stephen A. Douglas and South Carolina senator Andrew Pickens Butler for violent, vicious, and personal denunciations. Douglas was a target for his central role in the Kansas-Nebraska Act that had started “the crime.” Butler was not only a southerner but was from the state that seemed to perennially menace the Union. Although Sumner gave Douglas a good scorching, his insults leveled at Butler shocked Senators and spectators in the gallery. Butler was not in the chamber that day, which made Sumner’s verbal assault seem cowardly. Yet the words and imagery were a stunning example of Sumner at his crudest, and they stunned his audience. He described Butler as having “chosen a mistress . . . ugly to others, [but] . . . always lovely to him; and though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight.” Sumner made it clear: “I mean the harlot, slavery.”

Steve Douglas was present during Sumner’s performance and was visibly agitated by it. He waited until it was over to defend himself and others. A heated exchange ensued.

“Is it the object,” Douglas exclaimed, “to drive men here to dissolve social relations with political opponents?” Sumner was disdainful. He took the conversation to a deplorable confrontation.

“I also say to the Senator,” Sumner snarled, “and I wish him to bear it in mind, that no person with the upright form of man can be allowed — ”

Sumner hesitated. But Douglas broke the silence of Sumner’s pause with two terse words, a low growl that had the force of a thunderclap: “Say it.”

And so Sumner did. “I will say it — no person with the upright form of man can be allowed, without violation of all decency, to switch out from his tongue the perpetual stench of personality.”

People were flabbergasted by the gutter language and the animalistic anger. During the speech, Douglas could not help but pace back and forth at the rear of the chamber, and at one point was heard to mutter, “There’s one damned fool who’s going to get himself killed by another damned fool.”

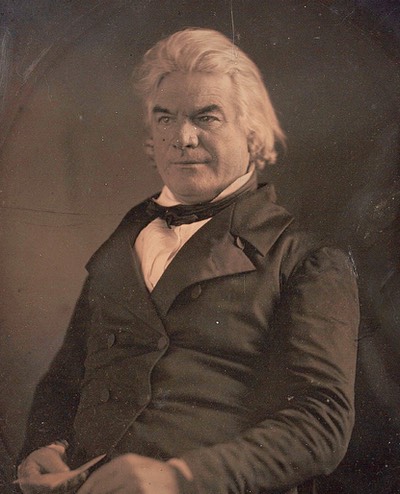

Andrew Pickens Butler

And soon enough, in fact, the man who was not there caused the most astonishing response to Sumner’s speech. Everyone, whether from the North or South, had looked down or away and had shaken their heads and clinched their jaws when Sumner painted Andrew Pickens Butler as consorting with “the harlot” slavery. Butler was elderly, a white-haired gentleman of the old school, soft-voiced and flawlessly polite, a learned jurist whose education and command of classical literature matched or exceeded Charles Sumner’s. Yet Sumner had mischaracterized this beloved man as a raving zealot and worse, he had said that Butler “with incoherent phrases, discharged the loose expectorations of his speech.” Everyone had gasped at the phrase, and not because, as many historians have concluded, it accused Butler of being a drunkard. It was because Charles Sumner was mocking Andrew Pickens Butler’s speech impediment.

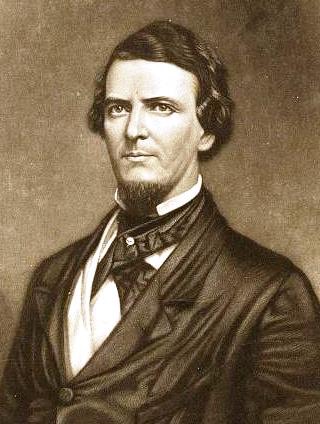

Thirty-eight-year old Preston Brooks spent a sleepless night following the final day of Sumner’s speech. Brooks was a second-term congressman from Edgefield representing South Carolina’s storied Ninety-Six District, and for that reason alone he felt compelled to punish Sumner for the insults aimed at his home. But Brooks was even more angered by something personal. Andrew Pickens Butler was his cousin.

Preston Brooks was an unlikely man for a reckless deed. He was known for his “truth, sincerity, kindness, courage, and courtesy,” and a friend rightly described him as taking “more pleasure to repair a wrong done by himself than to right one inflicted by another.” Yet the times had a way of transforming such men into somone unthinking and impetuous, even in their acts of deliberation. It was the kind of thing that later would cause the war.

Tossing and turning, Brooks hatched the idea of confronting Sumner in a Capitol hallway, but he worried that it either would give someone a chance to intervene or would provide Sumner a way to escape. He also thought about using a horsewhip but concluded that it would attract too much attention. In any case, Sumner could grasp it and reduce the encounter to an unseemly tug of war. Brooks intended for the thrashing to be seemly.

Preston Brooks

He chose May 22 for the date and the Senate chamber for the setting. He waited for adjournment and then strode in with the most inconspicuous weapon he could think of, a gutta-percha cane about the diameter of a man’s thumb. Even he was to be surprised by the damage it could do. The place had almost emptied out, and the few Senators remaining possibly only pretended not to notice as Brooks approached Sumner’s desk. There was no Senate office building then. Members often worked at their desks, and Sumner was writing letters at his. He glanced up as Brooks began to speak while raising the cane: “I have read your speech twice over,” he said quickly. “It is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a friend of mine.” While still speaking, Brooks began striking Sumner on his head.

There were about a half dozen blows. The cane whistled and made sharp snapping sounds on contact, itself snapping into several pieces during the assault. Sumner was trapped by his desk and nearly blind from the first smack of the cane, but he became a mass of frantic motion as he violently dislodged the desk from the floor, lurched forward, and fell to the carpet. Those who rushed to him feared he was dead.

For northerners, the attack on Charles Sumner exemplified everything that was loathesome about the southern “slaveocracy."

The immediate aftermath was confusion and disbelief, the sort of reaction one would have to a talking dog or an amputated limb that began functioning on its own. Sumner was not dead, but he had suffered serious physical injuries and would cope with nervous disorders for the rest of his life. With the exception of a few hours of attendance he attempted the following February, he did not return to the Senate for almost four years. When his term ended during this time, the Massachusetts legislature reelected him despite his absence abroad, and his desk in the Senate chamber remained empty as a reminder of southern barbarity.

Committees from both houses filed reports, but they countered each other on partisan lines, and the only meaningful result was a resolution for Brooks’s censure that caused him to resign. His district in South Carolina promptly reelected him, and southerners from all over the region began sending him canes in tribute. The stark contrast of those gestures to the solemnly dignified one of Massachusetts was inescapable and disconcerting. There was the irony that Preston Brooks, who had a distinguished record for heroism in the Mexican War and the political reputation of a man careful with words and heedful of deeds, was forever set in historical memory exclusively for his attack on Charles Sumner. He died from a respiratory infection the following January, and by then the “Crime Against Kansas” speech that had caused his rash act had been published as a pamphlet. It became a bestseller in the North.

Charles Sumner refused to have the coat he had been wearing cleaned. One evening in his rooms he showed it to a visitor whose long beard and glowing eyes reminded people of an Old Testament prophet. The coat’s collar was crusted with blood. John Brown gazed on it as one would a holy relic. But it was really a portent.