America has a birthday coming up, one in addition to the traditional one celebrated in July. For it was 230 years ago this Thursday, May 25, that thirty men gathered in Philadelphia to begin revising the Articles of Confederation. They were a vanguard, for an additional twenty-five delegates would gradually arrive, and the convention wound up writing an entirely new document that became the United States Constitution. The process took four months, a span so lengthy that a quarter of the delegates were already gone when the convention adjourned on September 17. But of those there at the start and at the end, the presiding officer was the most unwavering. His fellow delegates unanimously elected him to that post in the convention’s first piece of business that May 25, 1787.

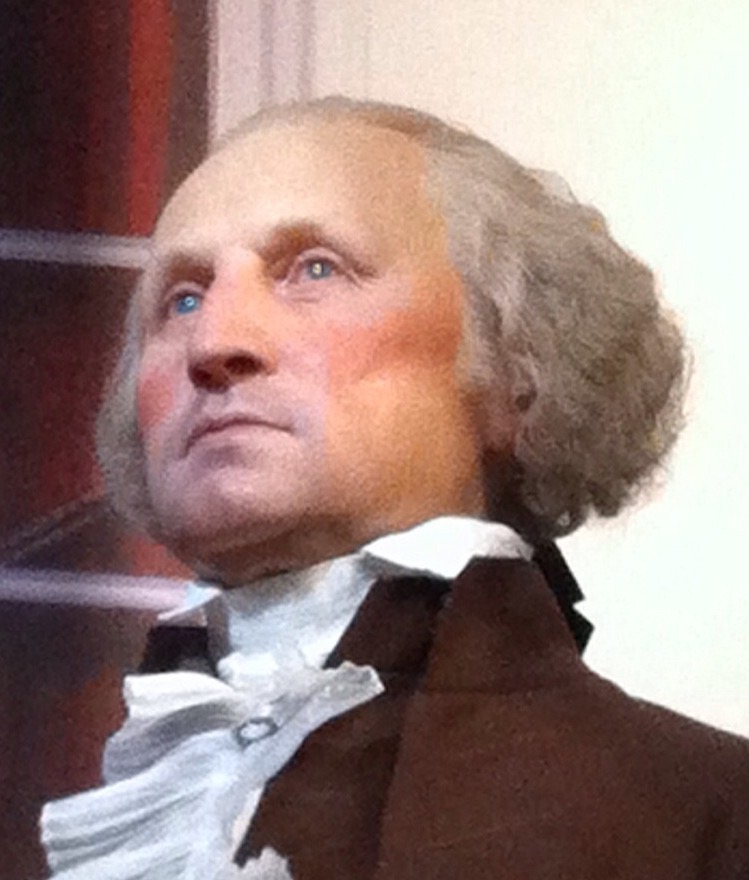

Twelve state legislatures had appointed delegates, with only Rhode Island refusing to participate. The process produced a group of men who would have been dazzling if assembled anywhere in the world. Pennsylvania’s Benjamin Franklin was the oldest, and the youngest was New Jersey’s Jonathan Dayton, more than fifty years Franklin’s junior. But the wide range of years did not matter where intelligence, a steady and reliable command of history, and a sense of stunning opportunity were brought to bear. The average age of the delegates was early forties, and George Washington at fifty-six was among the older men. That was fitting, for it added to the gravity that Washington’s fellow Virginians James Madison and Edmund Randolph knew he would bring to the event. He was clearly the head of the Virginia delegation, and nobody was surprised when Robert Morris moved that Washington preside over the convention itself, which approved him without a dissenting vote. The role removed him from debate, which was best considering his dread of public speaking, but it also elevated him above quarrels while fixing more firmly for everyone his future. Whatever the convention did about an executive department of government, its actions would be predicated on the belief that the executive would be George Washington.

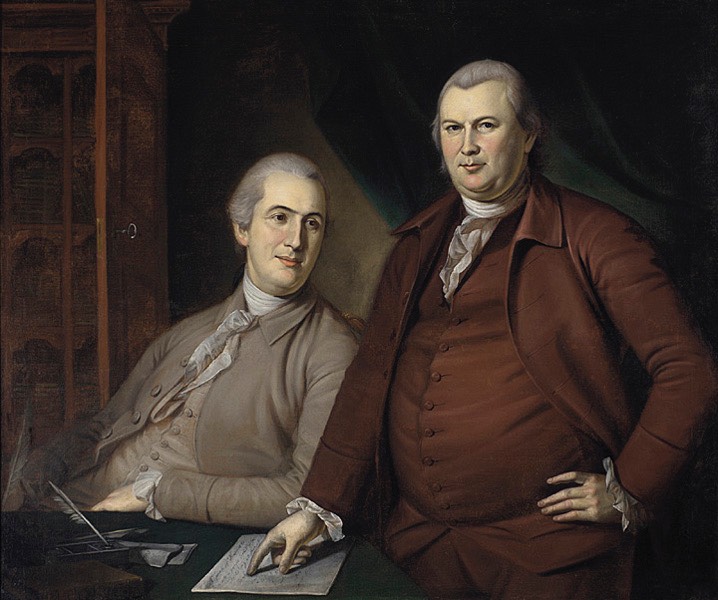

Almost all of the delegates knew him, and to some he was quite close. During the months the convention met, Washington stayed with his friend Robert Morris. They had come to know each other during the war when Morris’s gift for turning dross to gold was being applied to the complex problem of America paying for things without money. Some people hated Morris, usually for the obvious reasons. He was wealthy beyond calculation, having made a fortune in partnership with another rich Philadelphian, Thomas Willing, but some had also seized on the idea that as the government’s chief financier Morris was a crafty thief rather than a committed patriot.

Washington never doubted him. In the bleakest days of the war, Morris never forgot the country’s soldiers. Sometimes he paid them with his own money. Morris and his wife Mary looked the parts of the portly magnate and his elegant spouse. Mary was from the prominent White family, a Maryland clan that boasted high clerics and extensive connections, and she could be sharp in her judgments of people, but never of Washington. She had always found him the perfect guest in her home. Not only was he unfailingly considerate in following the household’s routines, he shared her fondness for public events like concerts or a quiet evening playing cards.

George Washington

Soon after he arrived in Philadelphia, Washington called on Benjamin Franklin, who opened a new cask of beer for the occasion. It was difficult to find anyone in the world who did not know of Franklin and almost as difficult to find anyone in America who did not know him personally. Like Washington, Franklin received letters from all over and seldom failed to answer them, making him the rare instance of the celebrated but accessible man. When the two clinked their foamed glasses that spring afternoon in Philadelphia, they were the most famous Americans in the world, both legends while living. Franklin was eighty-one and showing it with a stooped frame and crippling gout that required him to be carried on errands in a sedan chair. Anyone else would have seemed like a pretentious pasha, but people loved Franklin and indulged him his crochets as well as his needs. Pennsylvania had made him a delegate to the convention, and he realized that it was likely to be his last public act. The country was fortunate that his mind was as sound as his body frail. Franklin could talk in riddles and make sense.

During the coming four months in Philadelphia, long days in the sweltering chamber of Independence Hall gave way to pleasant evenings often filled with close friends from the Revolution. Former and future Philadelphia mayor Samuel Powel and his vivacious wife Eliza were delighted to renew Washington’s acquaintance. Eliza was a Willing, and her brother Thomas was Robert Morris’s business partner, one of many examples of the cozy interlocking connections in Philadelphia society that disparaged outsiders if they didn’t measure up. Franklin always had found such pretensions amusing while playing their games better than most, but the Powels were a cultured couple who also happened to be nice and able to don the easygoing charm of people with money and manners. Samuel had been mayor when America declared its independence and was so highly regarded that when he left the office in 1776, Philadelphians had not replaced him. They instead left the post vacant until he was ready to fill it again, which would be a couple of years after the convention.

A close associate of Robert Morris during the Revolution was also a Pennsylvania delegate. Gouverneur Morris was no relation to Robert but had been his protégé in the financier’s office during the war and like his chief, a staunch friend of Washington and the army. Gouverneur was as tall as Washington but physically unlucky. He had badly burned an arm making it almost useless, and had lost a leg in what he called a carriage accident but rumor attributed to a fall from a lady’s balcony when her husband unexpectedly showed up. As a consequence, Morris had the look of a peg-legged pirate to match a devil-may-care attitude mixed with flawless manners, a ready wit, and the reputation of a great lover. Hearing about Morris losing his leg, usually prim John Jay said it was a pity Morris had not lost another part of his body.

Gouverneur Morris and Robert Morris by Peale

Morris was named after his mother, Sarah Gouverneur, who was descended from French Huguenots long in residence in Holland before migrating in the early 1660s to what was then New Amsterdam. The Morris family was wealthy, and Gouverneur was raised at the family manse Morrisania, a rural seat covering much of what is now the Bronx. His father died when Gouverneur was ten, and thereafter his mother’s influence was palpable, improving his impeccable French as well as developing his independent streak to match hers (she would be a steadfast Loyalist during the Revolution). He received an outstanding education augmented by a prodigious intellect that had him attending King’s College (now Columbia) when he was twelve years old.

Washington liked Morris immensely for many reasons. His resolute behavior during the Revolution, his commitment to nationalism, his impressive learning, his sober pragmatism for all his sophisticated charm were among the traits that impressed Washington. As a youth, Morris had learned not to take himself or the world too seriously. He looked askance at politics as a process in which “the madness of so many is made the gain of so few.”

It was natural then that during one of the few breaks in the convention Washington asked Gouverneur Morris to join him and others on a fishing trip. Their group also visited Valley Forge, and everyone had the good sense to leave the general alone with his thoughts as he wandered over ground where men had bled through their feet and the army had shivered on the edge of the world. Gouverneur Morris had been among the few in the Continental Congress to visit the encampment in that horrid winter of 1777, and the sight had shaken him like nothing in his life. There was nothing devil-may-care about Morris when something mattered. The instant he returned to Congress, he began talking himself hoarse and working tirelessly to get those soldiers clothes, shoes, food, money, weapons, encouragement. George Washington liked him immensely.

How much impact Washington’s presence as well as his reputation had on the convention’s discussions about establishing the presidency is difficult to gauge. No conclusive records show in what way Washington and James Madison conferred during the convention, but evidence from letters and diaries suggests they met frequently. The sixty evenings that Washington remained at home at the Morris residence gave him opportunities to discuss trends at the convention with Morris and guests such as Gouverneur Morris and James Wilson, who was to be the principal architect and proponent of Article II that set up the executive.

In the convention, Washington as presiding officer had the excuse of remaining quiet and watching the debates from a presumably impartial perch, but he voted as a member of the Virginia delegation. Even so, those votes must also be deduced because no records were kept of Virginia’s internal tallies. It is certain that his vote always fell on the side of a strong national government, but by August the changed complexion of Virginia’s delegation was requiring diplomacy. Departures from the convention and disaffection by those who remained left Madison with only one dependable ally on the Virginia delegation, which forced Washington to break ties. He seems to have done so on several occasions to mollify discontent, which is to say he sometimes seems to have voted against his inclinations to keep the peace. In the end, he was unsuccessful.

Because in the end, no compromise, no accommodation, no placation could put to rest George Mason’s reservations about the government as proposed. He was Washington’s friend of many years, a fellow Virginian, but his disagreements with the document were unyielding. Worse, Mason was not alone. To Washington and Madison’s chagrin, Virginian Edmund Randolph joined Mason in opposition. Evidence suggests that Washington tried to the very end to avoid these defections from his own delegation, for they were not only embarrassing, the opposition from these influential people could have wrecked the Constitution’s chances for approval in Virginia. On the convention’s final day, Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts proposed that the population ratio for apportioning the House of Representatives be lowered from 1 congressmen per 40,000 to 1 per 30,000. There was apparently more to this move than merely a compromise to appease those concerned that the House was insufficiently representative. A third delegate planning to withhold his approval was Elbridge Gerry, a member of Gorham’s delegation. During the discussion about lowering the ratio, Washington broke his silence to support it, ending discussion and ensuring its passage. It is likely that the initiative was a last effort to mollify not just Gerry, but Washington’s fellow Virginians. If so, it did not work.

George Mason

Randolph spoke of holding another convention. Mason insisted the only remedy was a bill of rights to protect basic liberties from the elasticity of “necessary” intrusions that could on the whim of a congressional majority be deemed “proper.” The delegates listened politely. Some even took the time to explain in great weariness that the seventeen weeks of work were enough, that it was time to go home and let the people decide. Even in its fatigue and mild disbelief over the lunacy of starting over or tacking on more qualifications, the momentum of the majority was undeniable and irresistible. The delegates listened politely, but they engrossed the document, and thirty-nine of the original fifty-five who happened to be in the hall signed it, beginning with George Washington.

Randolph, Mason, and Gerry did not sign the Constitution, the only delegates in attendance who refused to do so. Mason had said dramatically that he would cut off his hand rather than sign. Some delegates were likely willing to fetch him a saw. He left Philadelphia with Maryland’s James McHenry and was in such a foul temper that traveling with him was a trial.

Washington kept his counsel about Mason, but he was not pleased by the behavior or the prospect of obstruction. The Constitution, he said, was now “a Child of fortune to be fostered by some and buffeted by others.” Washington confessed to having no idea how the people would receive this child of fortune. He was certain, though, that its failure would seal the fate of his country, just as he knew its success would sentence him to a thankless duty with unimaginable costs.

Yet if any pride guided his actions in that crucial time for his country, it was in his resolve to not allow “melancholy proof” of the self-satisfied prophecy of tyrants everywhere: “mankind when left to themselves are unfit for their own Government.” The Revolution for liberty, the war for independence, the grueling pace and grinding fears of months spanning to years would all have been for nothing. “I am mortified beyond expression,” George Washington had said, opening his heart, “when I view the clouds that have spread over the brightest morn that ever dawned upon any Country.” He knew it would be worse than a passing storm. Dawn would give way to dark. Tyrants biding their time in the shadows would smile.

Dazzling if assembled anywhere in the world, those brilliant men led by a courageous one were in America. They argued with and accommodated one another, determined to thwart tryants and prove that their country was an exceptional place of extraordinary people. That began happening more than two centuries ago, on May 25, America's other birthday.