Only hours passed after April 14, 1865, before authorities had arrested almost all the conspirators involved in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the attempted murder of Secretary of State William Seward. In part, that was because anyone suspected of the most remote complicity was collared until the jails were bulging. But Lincoln’s assassin eluded capture for 12 days and when finally found refused to surrender. Sgt. Thomas “Boston" Corbett violated orders and shot John Wilkes Booth. He died shortly afterward. It was on April 26, 150 years ago, but it wasn't the end of the affair. Rather it was the start of a deep mystery beginning with who Booth was, who he became, and how he seemingly managed to cheat death, after a fashion.

John Wilkes Booth is unique in the rogue’s gallery of American assassins. They are usually disaffected outcasts who skulk on the fringes of society. They strike famous targets because to slay them imparts distinction, even if it’s infamous, and even infamous distinction can be desirable for a certain type of gray person whose life is without meaning.

Yet this wasn't John Wilkes Booth at all. Growing up in rural Maryland, Booth was part of a large, famous, and loving family. Johnny was especially close to his sister, Asia, who described her brother in a memoir long after the assassination. Their childhood was tranquil, a pastoral idyll full of imaginative play and barefoot gambols, more the stuff of Norman Rockwell than Norman Bates. Their renowned father did not want his children to follow him on the stage, but the lure of the theater was strong, and his two oldest sons, Junius Jr. and Edwin, became accomplished actors. Edwin, in fact, was already being hailed the “prince of players” when Johnny began taking bit parts under a stage name. He didn’t want to cash in on his family’s reputation.

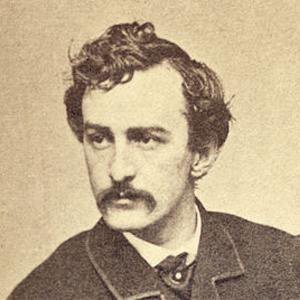

John Wilkes Booth

After a faltering start, he came into his own and was using his own name to add luster to the family’s. Good looks, exuberance, and a melodious voice quickly transformed the clumsy stock player into a rising star, a matinee idol for many, and an increasingly proficient artist for a growing cadre of discerning critics. At the height of his fame, John Wilkes Booth was receiving top billing and packing houses in both the North and South. He was earning at least $20,000 a year, the equivalent of almost a quarter million dollars today, but he never acted like a “star.” On the contrary, his thoughtfulness touched fellow actors. He was a generous friend. He never upstaged anyone during performances.

Women found Booth irresistible. They swooned at his plays, threw themselves at him in private, and collected photographs that featured his wavy black hair, strong chin, aquiline nose, dashing mustache, and eyes that could quicken hearts while melting them. A Quaker matron, skeptical about the gewgaws of the theater, gave in to curiosity and saw Booth perform to see what all the fuss was about. The experience stunned and dazed her. She likened him to “a new blown rose with the morning dew upon it.” He lived up to that image with sincere chivalry. A friend once saw him cutting out signatures from love letters that would have embarrassed their senders. “They are harmless,” he laughed, “once the sting is removed.”

The war changed him. Obsessed with the Confederate cause, he became so overbearing about it that he alienated friends and nearly estranged his brothers, especially Edwin, who heartily supported the Union. Johnny promised his doting mother that he would not become a soldier, but he became a Confederate secret agent instead. Perhaps he was doing the bidding of shadowy superiors when he pulled the trigger at Ford’s Theater, but even if that were so, his immediate motive was overtly political and apparently personal. Shocked and disconcerted by the Confederacy’s defeat and convinced that Lincoln was a Caesar awaiting a Brutus, John Wilkes Booth resolved to play that role in a spectacular and very public fashion. Days later, weak and on the run in the Virginia backwoods, Booth and a fellow conspirator were finally cornered in a tobacco barn on the Garrett farm near Port Royal. On April 26, 1865, he was mortally wounded. When Asia heard the news, her heart pounded “like strong machinery,” and she was little comforted by brother Edwin’s saying that their brother was “dead to us now, as he soon must be to all the world.”

Yet it was more than odd that to all the world John Wilkes Booth had only just begun to live. The War Department concealed the whereabouts of his grave to prevent it from becoming a Confederate shrine, and that naturally led to the suspicion that he had never been found and was far from dead. Newspaper accounts had him gambling at European casinos, attending operas in Vienna, riding in carriages in Paris, or openly touring Vatican City. He was sighted in Bombay or spotted in Ceylon. Edwin was supposed to have had a tearful reunion with him on a foggy London Street. Over the years, he became everyman doing everything everywhere. He was a pirate marauding on the China Seas or had resumed acting in the Far East. He was a castaway on a South Sea Island, hiding on California's Russian River, or living in the suburbs of Chattanooga, Tennessee. By the 1880's, men here and there were openly claiming to be him, and deathbed confessions multiplied. Some were remorseful; some were gloating.

In 1903 when David E. George died in Enid, Oklahoma, stories surfaced that George had claimed to be John Wilkes Booth. Tennessee attorney Finis L. Bates soon showed up in Enid and insisted that the embalmed corpse of George was actually that of John St. Helen, which turned out to be a double confirmation for the gullible: Bates said that St. Helen had confessed to him that he was John Wilkes Booth. The “George-St. Helen-Booth” body went unclaimed, which allowed Bates finally to get hold of it and begin hiring out the “Booth mummy” to county fairs. The freakish exhibit remained a popular sideshow attraction for years, as were a half dozen skulls, all supposedly Booth’s severed head that were simultaneously displayed in different carnivals rambling through rural America in the early 20th century.

The "Booth Mummy"

It did not matter that in 1869 Booth’s body had been exhumed from his secret grave in the floor of the Old Capital Prison, returned to his family, positively identified, and placed in the family plot at Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore. It did not matter that all the sightings were bogus or that all the men claiming to be Booth were frauds. The belief persisted that Booth did not die on the porch of the Garrett farm in 1865, that he instead escaped to Texas or Tennessee or Tasmania or wherever. Eternally tormented by the consequences of his horrid deed, Booth had become an American version of the Flying Dutchman or the Accursed Huntsman.

Asia Booth Clarke

Edwin had told Asia to “imagine the boy you loved to be in that better part of his spirit, in another world,” but she could not help herself. She obsessed over the stories that grew like weeds around Johnny’s name. She brooded over tales that told of his carrying a bullet with Lincoln's name on it, of his using a diamond ring to etch on a window pane boasts of poison plots. She lived long enough to see the imposters multiply, the theories about his motive proliferate, the psychological dissections of his personality turn him into an irredeemable monster. Rather than the barefoot boy on a Maryland farm, he became a violent child who had tortured wildlife and killed cats for sport.

She tried to come to terms with it all in her memoir. For many years it remained only a handwritten manuscript until it was published in 1939, fifty-one years after her death. Finally Asia was able to relay a whispered message from her family: People who saw the assassination as "a political affair—the work of the bloody rebellion” had failed to notice the real human tragedy by imposing a grand design on what was actually a sordid murder. Those who knew Johnny knew that what he had done was, and always would be, “a crime.”

John Wilkes Booth’s last performance was played during the final act of a national tragedy, a vile murder scene ironically staged in a theater. “Do recognize him some where,” a former admirer scrawled on the back of one those famous photographs, “& kill him.” The bullet that felled Booth didn’t kill him at first but paralyzed him, and as he lay dying on the porch of the Garrett farm, he asked someone to hold his hands in front of his face. He was looking at them when he murmured his last words: “useless — useless.” He was just days shy of his twenty-seventh birthday.