Afraid of heights? Most people are, but not, we’re often told, from a fear of falling. Rather, it’s from the feeling that an irrational urge to jump will cause us to hurl ourselves off a high place, even if we have to vault over safety rails. This seems most unlikely, though. It probably derives from an instinctual fear of the fatal misstep in a perilous place. Put someone in a spot that gives him vertigo by overloading his senses, and he’ll do something stupid. Then the “fear of falling” becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Anyone who knows anything about prophecies knows the self-fulfilling kind always turn out badly.

That was true for our subject today. It concerns a young man who should have been in his prime — he was 22 — and had achieved enough fame as a daredevil to have admirers stand for his drinks and pay for his meals. His travels were reported in newspapers, his slogan became a popular catchphrase that turned up in headlines and banquet toasts, and his audiences ultimately numbered in the thousands, sometimes comprising entire communities. Old codgers, young roustabouts, moms with babes in arms, stout matrons — you name it, they all turned out to watch somebody who possessed, as one journalist gushed, “what few have arrived at, contempt of danger.”

His name was Sam Patch, and he was in every respect an ordinary fellow except he deliberately jumped from high places, fell considerable distances, and lived to tell about it. At least, he lived until Friday, November 13, 1829. On a chilly day in Rochester, New York, Sam Patch killed himself in front of 12,000 people. Afterward those people had to live with the fact that they had turned out to see Sam on the chance — and there was no other way to put it — on the chance that Sam Patch might kill himself.

It didn’t start that way, either for Sam or the people who watched him. Born in 1807 into a relatively large family, he was the next to youngest of six children in their Pawtucket, Rhode Island, home, which wasn’t at all a happy place. Sam’s father was an alcoholic, his mother beleaguered, and his siblings were unremarkable except for the coping mechanisms that the children in such families develop. For Sam, coping consisted of getting out of the house as soon as he could by going to work in one of Pawtucket’s textile mills at the ripe old age of 7.

The mills valued children because they could negotiate the small spaces between and under the enormous carding machines, spinners, and looms. Children could perform unskilled maintenance tasks and routine cleaning chores for the eleven hours a day the machines ran. It’s often portrayed as dangerous work, but it really wasn’t, and the people who ran the mills were considerably more pleasant than Sam’s dad, and there’s evidence they took an interest in Sam. Someone taught him the art of running complex spinning machinery, and consequently he became a Boss Spinner. That made him a highly skilled and valued artisan able to command top wages and toil with a measure of independence as long as he showed up for work and turned out the required yardage of material.

The work wasn’t risky for anybody really, but it was physically demanding and mentally enervating. Children often had to be waked up even though the machinery raised an incessant din, and spinners had to combine a nuance of touch with brute muscularity to produce uniform thread. Everybody had a desire to blow off a bit of steam, and the boys managed this by jumping into the Blackstone River that powered the mills. The water was turbulent and rapid at Pawtucket, which was the reason the mills were situated there, and the rapids featured an impressive waterfall. The kids jumped into the waterfall, and like the mill machinery that only seemed dangerous, the water was perilous only for the careless.

Sam Patch had early on joined the fun, and he became an accomplished jumper by mastering the mode for the safe but thrilling leap. The boys knew that care should be taken to align the body as straight as possible with feet down from the start and through the finish. It was just as important to inhale sharply during the descent because velocity by the time one reached the water meant a deep plunge that required as long as a half minute to return to the surface. But it was a grand surface, roiled by the falls but coldly bracing, and so highly aerated that a jumper didn’t hit the water but slid into a soft liquid mush that tickled and enlivened, making for the perfect end to the perfect thrill: one that had elements of danger but certain safety stemming from proper technique. It didn’t matter then that the 80-foot height of jumps from the roof of a mill building seemed treacherous. It was diverting.

All the boys did it, but Sam became famous because he left Pawtucket and started jumping, mainly by accident, for a living, after a fashion. Nobody knows why he left Pawtucket with its good, steady job. Perhaps the easiest answer is that Sam wasn’t a steady sort of fellow. He was irascible with the children who worked under him, and he seems to have ruined a couple of business partnerships with his pugnacious attitude. The blame for these lapses and flaws possibly stemmed from strong drink. Like his father, Sam drank often and more than was wise.

If his leaving Pawtucket was motivated by a desire to see something of the world, by 1827 he had made it only as far as New Jersey. His marketable skill was limited to places that had textile mills, so it is understandable why he wound up in Paterson working as a spinner in a mill there. What is less clear is why he jumped off a cliff into the Passaic River that September. According to Paul E. Johnson’s insightful study that explores the brief popularity of Sam Patch from a cultural perspective, Sam’s jumping was part of “the angry industrial history of Paterson.” For instance, the jump was to spoil an entrepreneur’s opening of a new entertainment business and the raising of a bridge across the Passaic. Sam grabbed the attention by mounting a protest with a perilous spectacle. The large crowd of the curious who had gathered to watch the bridge being put in place were astonished to see a young man in white linen trousers and a simple blouse step off a sheer cliff and drop 70 feet like a dart, bringing up his knees just before reaching the water and suddenly straightening them for entry feet-first the way it was done at Pawtucket. A long silence followed, as much from bewilderment over what the jumper had been thinking as from the fear that he had smashed himself to bits. But he popped up, and the crowd cheered, relieved by Sam’s survival and appreciating his bravado. All the crowds would be like this when Sam popped up, until the day he didn’t.

Why did he jump? Drunk went one explanation; lovelorn said another. Sam Patch said it was neither. He was determined, he told a newspaper reporter, to perform great “art.” Building a bridge was one type of skill, and jumping off cliffs was by gum an equally stupendous one. Well, sure, we might agree that the skill of surviving repeated instances of feet-first hurtles from daunting heights is worth marveling over. But Sam’s strange comparison makes you scratch your head. Someone who sees jumping off of a cliff as comparable to building a bridge is simply touched.

Nevertheless, Sam’s manifesto was based on just that proposition and was summed up in what became his tag line, “Some things can be done as well as others.” The grammatical locution is vague enough to be confusing, because it could mean “some things can be done in addition to other things.” But that isn’t what Sam Patch meant. His pronouncement was that some things can be done as well as others can be done.

Yes. Perhaps this strange phrase made a bit of sense in explaining the first jump at Paterson, but its pertinence became remote when applied to the rest of Sam Patch’s “career.” On July 4, 1828, he again jumped off the cliff at Paterson, purportedly to help wrest control of the town’s Independence Day celebration from elite citizens who were excluding the common folk from fireworks displays and fancy banquets. It seemed a better reason than satisfying an inclination for exhibitionism.

This was a jump advertised by word of mouth, and Sam’s audience numbered about 4,000 people who lined the cliffs around the Passaic River’s chasm. At 4:30, he made his way to the rim, glanced down into the chasm, and began pulling off his jacket and shoes. The preparations excited onlookers, and as the crowd pushed forward for a better look it almost shoved those in front over the cliff’s edge. Sam turned around and said a few words, a feature of his act that he tried out for this jump and kept for future ones. Nobody remembered what he said in Paterson that July 4, though, because they wanted to see him hurl himself into the river, not make a speech. He eventually obliged with the hurling part. And when he reappeared on the surface of the Passaic, and the roaring cheers and clatter of applause echoed off the chasm’s walls and reverberated across the Passaic, Sam Patch was on his way to becoming a showbiz sensation. In the two years remaining to him, he would jump from high and higher places at Hoboken, New Jersey, at Niagara Falls, and finally at Rochester, New York.

The reasons behind Sam Patch’s embarking on this strange vocation, and the appetite of his audiences for watching him risk his life have been pondered by others, including the aforementioned Professor Johnson. Let’s consider here the unusual way that Sam Patch became famous. Counting the events listed above, Sam Patch’s fame rested on eight leaps, although there is some evidence that he also jumped into a small waterfall on the Passaic River north of Paterson. In any case, even adding that event to make for a total of nine jumps, Sam Patch’s reputation as a daredevil rested on stunts the actual doing of which consumed about thirty seconds over a two year span. That amounted to roughly .000000476 of Sam Patch’s life during those twenty-four months, which left him with a great deal of free time, most of which nobody can account for. Sam never married, never bought a particle of property, and does not appear in the census of 1810 when he was a toddler or of 1820 when he was a teenager. He died a daredevil with nothing more to his name than the clothes on his back, a slogan, and a pet bear he acquired to cultivate the reputation of an eccentric. Lacking the things that make for a normal person’s identity, Sam Patch existed solely as a creation of his exploits, which made him more of an idea than a real person, ultimately even for himself. He developed a habit of speaking of himself in the third person, making bombastic pronouncements such as, “With Sam Patch, there’s no mistake!” He might as well have been talking about a patent medicine.

Another startling aspect about Sam’s exploits derives from that half minute. It emphasizes the physical nature of what he was doing, especially as to the increasing probability that it would kill him. A fall of 80 feet, such as the leaps the Pawtucket boys were making in the Blackstone River, takes about 2.25 seconds and achieves a velocity of about 48 mph. Hitting anything with even a scrap of surface tension at that speed is likely to cause injuries, but the falling water at Pawtucket was a soft mush of forgiving bubbles. The same was true for Sam’s three leaps at Paterson, where the height was comparable and the water was similar to what he was accustomed to at Pawtucket. Something about the Passaic River at Paterson seems to have worried him, though, because he canceled a scheduled fourth jump there that was supposed to occur in late July. A New York newspaper reported that “Mr. Patch has resolved to leap no more from the place he had chosen heretofore,” and provided only the explanation “that Sam felt rather ‘ugly’ about it the last time.”

It’s not clear what that meant, but Sam Patch never again performed for “causes” but for show. On August 6, 1828, he jumped from the masthead of a ship anchored in the Hudson River for the amusement of about 500 spectators on a “shaded green” at Hoboken and hundreds of others on surrounding boats. The platform stood 90 feet above the Hudson, and as he hurled himself clear of the ship and rapidly descended toward the water, his body deviated from the straightened form of Pawtucket and Paterson. Instead, he twisted to one side, and his feet rose from the perpendicular, causing him to fall on his back. He made a mighty splash, which made the event more spectacular, but it was the sign of an impact that likely hurt Sam Patch, and probably quite seriously.

In the first place, the Hudson’s surface was not the effervescent cushion created by cascading falls. And second, the height was immensely dangerous given that difference, for falling 90 feet had Sam traveling at almost 51 mph when he reached the water. Given that height and his ungainly form, it was an impact rather than an entry, and the Hudson River would have been only slightly more forgiving than plowed ground.

The fall bruised his face, but there’s no telling what it did to his back. He put up a stoic front when fished out of the river, but little wonder that Sam Patch never again jumped into this type of water from such a height. More telling was the fact that he didn’t jump into any water at all for at least a year, suggesting the possibility that he was trying to mend. Moreover, he disappeared from public view (and the historical record) after the Hoboken jump, and the best efforts to trace his movements can only guess that he might have been working in a textile mill around Philadelphia. When he reappeared, it was because he had accepted an invitation to jump at Niagara Falls as part of efforts to lure locals with lowbrow spectacles in the off-season. As Sam Patch traveled to Buffalo on the recently completed Erie Canal in that autumn of 1829, he was always drunk.

In fact, nobody would ever again see him completely sober, whether at morning, noon, or night. It marked a change in a man who previously had gone on benders but always had cleared his head for the demanding work of running a huge, complex spinning machine. Constant inebriation could have been nothing more than the inevitable degeneration of an alcoholic, but it also could have stemmed from coping with a serious injury caused by the Hoboken jump.

Even more disturbing for this particular fellow, the shock at Hoboken might have planted in Sam Patch the very fear that the newspapers had praised him for vanquishing. Booze can supply a measure of dutch courage even as it anesthetizes the shame of cowardice along with the chronic pain of a busted back. But it also balances bright buoyancy with dark depression, and Sam was swinging between those two poles with troubling frequency in the autumn of 1829. His hail-fellow-well-met jollity always slithered into glum fatalism as day turned to night, and the admiring lads who stood for his drinks wound up paying for more than the whiskey, gin, and brandy. They ended long blurry nights listening to Sam Patch's slurred mumblings about death.

He jumped twice at Niagara Falls, which was twice more than any sane (or sober) person would have done. The place defies definition, beggars description, and assaults the senses with a raw power that is physically discomfiting and emotionally terrifying. By the time Sam Patch was there, many of the staircases and observation decks that we still use to view the cascade were already in place, and even the most jaded visitors were always impressed by the sound of the water — if the concussive force of a battery of heavy artillery constantly firing could be likened to sound. Niagara Falls turns sound into something pounding and abusive, something that is felt as blows to the gut as much as it is heard by the ear. Travelers always searched for descriptive words and usually wound up with “sublime,” but that is only true from a distance. Up close, Niagara Falls is more than menacing; it is clearly capable of smashing to atoms anything that falls into its clutches.

For good reason, many at Niagara Falls didn’t think Sam Patch would go through with his scheduled appearance on a rainy and cold October 6, and when he judged preparations for his jump as incomplete and postponed it, skeptics nodded and went home. Yet he returned the following day and jumped at a setting between the Horseshoe Falls and the turbulent crosscurrents on its flank that produce a lovely and surprisingly calm cushion of bubbly water at the base of the falls. Sam hit the spot as a bullseye. It was the falling into the cushion from 80 feet through the cacophonous pounding of the falls that was the trick, and after managing it for the small crowd on the 7th, Sam Patch was confident he could do it again for a larger audience. He would show them the wonders of doing some things as well as others and walk away with as much as $75 into the bargain. He scheduled another jump for ten days later and advertised it aggressively. He explained during one of his merry moments, “I thought I would venture a small leap, which I accordingly made of eighty feet, merely to convince those that remained to see me, that I was the true Sam Patch, and to show that some things could be done as well as others; which was denied before I made the jump.”

The second jump was from a platform that raised the plunge from 80 to 120 feet, and when it came off fine, the success apparently convinced Sam that aerated water negated the danger of jumping from extreme heights. But it’s likely the power of the falls at Niagara made them unique in their ability to alter the dynamics of not only water but air in ways that no other place could match. Otherwise an excessive height simply makes a fall exponentially dangerous. It was a point later made by Paris Parker, a peculiar fellow in Providence, Rhode Island, who had plans to jump from atop a commercial building and safely land on pavement 100 feet below by slowing his descent with umbrellas in each hand. Parker was fortunately dissuaded from an exploit that would have certainly killed him, but he had a point about the speed of a fall being determined by its vertical measure. We can be certain that neither he nor Sam Patch knew the fairly complex formula for gravitational acceleration, but Parker knew enough to make the commonsense observation that Sam Patch had begun to jump from places that were too damned high.

Just days after his triumphant second jump at Niagara Falls, Sam turned up in Rochester, the Erie Canal’s midpoint and the place on the Genesee River where its waters descend sharply in an impressive waterfall. “Some things can be done as well as others” and “Sam Patch against the world!” he proclaimed in announcing a jump there. “Having returned from jumping over Niagara Falls,” said the local newspaper, Sam Patch “has since determined to convince the citizens of Rochester that he is the real ‘Simon Pure,’ by jumping off the Falls in this village, from the rocky point in the middle of the Genesee River into the gulph below, a distance of 100 feet!”

On November 6, he made a flawless jump and immediately announced that he would jump again on November 13, but from a platform to raise the leap’s elevation to 125 feet. Most of the town gathered at the Genesee on that cold afternoon, and they waited and waited until Sam Patch finally showed up. He was so drunk that he could barely stand. He stumbled through the shallows to the little wooded island at the center of the falls and pulled himself up on a platform. He was swaying as he turned to deliver a rambling address in which he compared himself to Napoleon Bonaparte and the Duke of Wellington. He went on like that for almost a quarter of an hour, and it should have given responsible people both a reason and the time to stop him, but they didn’t. Later accounts claimed that concerted efforts were made to stop him. At least, that was the claim.

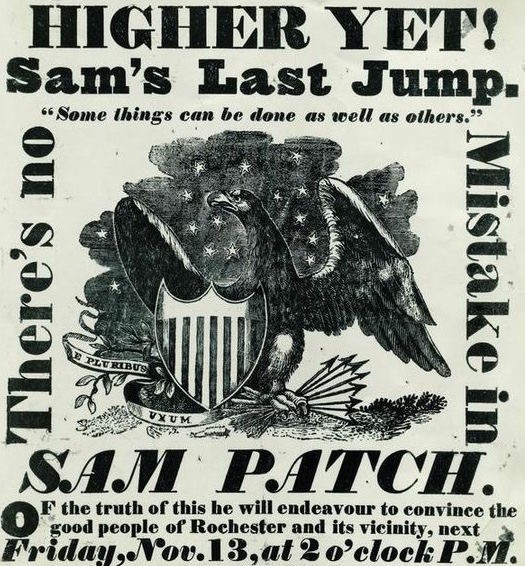

The handbill for the second leap at Rochester did not mean it would be Sam Patch’s “last jump” forever. But it was.

No, Sam was insistent, everyone later claimed. He stared at the crowd blankly while removing his hat and pea jacket. He unsteadily hunkered down on his heels, catapulted himself out, and for a fraction of a second fell as he always had. But 40 feet into the 125-foot plunge his form changed, and by the time he was nearing the Genesee his arms were windmilling and his body was out of kilter. The fall took almost 3 seconds, and his speed at impact would have been about 60 mph. The water probably killed him instantly.

We can only hope that the water killed him instantly. Surviving submerged would have made for a brief but agonizing ordeal. As it was, the Genesee took its time dragging Sam Patch seven miles downstream toward Lake Ontario. Four months after the jump, he bobbed up and was visible beneath thawing translucent ice. The good people from the little community of Charlotte, New York, pulled him out and thus ended rumors that Good Ol’ Sam Patch had faked his death and was having a hearty laugh while planning another leaping stunt.

For a while his slogan “Some things can be done as well as others” outlived Sam Patch as a popular catchphrase to describe everything from Andrew Jackson’s presidency to winning a mumbly-peg match. The pertinence of it for Sam was pretty thin after his first jump, but he made it freakishly fitting for his last. People scoffed that his demise had exposed the idea as applied to him to be a sham, but they more than missed the point that Sam Patch had been making for months in acrid barrooms. He had mused between shots of whiskey about life and leaps, but at the end of the long nights he fell silent for long pauses. Then he would mumble something about dying.

There was, after all, no mistake in Sam Patch. On November 13, 1829, he did what he had been talking about.