On the morning of May 29, 1806, Rachel Jackson likely knew why her husband was leaving home on a two-day trip, but she said nothing, even when in parting he casually said that there might be some difficulty with a Mr. Dickinson. Similarly Charles Dickinson had breezily said farewell to his wife with a promise that he would be home the following evening. Jane Dickinson might have known as much as Rachel, but possibly not. At nineteen, she was very young and carrying their first child. Charles was brash but not inconsiderate.

The two husbands were separately starting on a business trip, of sorts. They rode with companions for an appointment that in the preferred euphemism of the day was sometimes called “an interview,” meaning a duel. The argument causing this wasn’t an impetuous outburst, and the steps toward the interview had not been hasty. It was the product of six months of misunderstandings, heated exchanges, name-calling, and finally a blunt challenge quickly accepted. Ostensibly it grew out of a dispute over a horse race, but the serious turn of the disagreement suggested that it was really about something else. Jackson’s friend Sam Houston said as much later.

Andrew Jackson

The horse race resulted in a complicated affair because it was never run. Andrew Jackson’s “Truxton” was to be matched against Joseph Erwin’s “Ploughboy” with great sums of money in play. At the last minute, Ploughboy drew up lame and couldn’t run. The rules required Erwin to pay a forfeit fee of $800, which he pledged to do with notes, meaning IOUs, that he held from a variety of debtors and would sign over to Jackson. It wasn’t an unusual way to conduct a transaction in Tennessee during the first years of the 19th century, but not all of Erwin’s notes were near their due date for collection. Jackson demanded that at least half of the $800 be remitted immediately to pay partners who were expecting their money.

Erwin managed to set things right, but it took him long enough that the delay encouraged loose talk among Jackson’s friends that Erwin was trying to weasel out of his obligation. Erwin wasn’t acting in bad faith, and unsubstantiated charges that he was naturally angered his friends and family. For a while the episode resembled Shakespearean farce as a growing number of people carried increasingly distorted tales about what nasty remarks had been said by whom about whom. Overreactions followed. One of Erwin’s defenders was a young lawyer named Thomas Swann who caustically laid the blame at Andrew Jackson’s door, which wasn’t altogether fair, but the situation was moving beyond reasoned responses. Jackson judged that Swann was not worth killing, so he planned to beat him up. He found Swann at Winn’s Tavern in Nashville one afternoon and proceeded to whip him with a cane. The beating was cut short when Jackson tripped over the legs of a chair and went sprawling backward into the tavern’s fireplace. As we said, there were elements of farce.

Charles Dickinson

Unfortunately, the business took a deadly serious turn with the involvement of Charles Dickinson. A Maryland native from a prominent family, Dickinson had read law under John Marshall and carried letters of reference and introduction from the Chief Justice of the United States when he moved to Tennessee. Settling in Nashville, Dickinson hung out his shingle and began courting a pretty girl named Jane, who happened to be Joseph Erwin’s daughter — the same Joseph Erwin who owned Ploughboy. Charles and Jane’s marriage brought the lad into the world of plantation hospitality and planter amusements, which featured liberal doses of whiskey, high stakes at card games, and higher stakes at crowded race tracks with fast horses and heedless men. Dickinson lived the life with enthusiasm, and with his already overdeveloped sense of touchy honor inherited from a fine Maryland family he embraced the western way of protecting it. It was a risky situation for a lad in his twenties whose youth gave him a sense of invincibility; it was even riskier for a boy blessed with a steady hand and sharp eyes, one to hold a pistol and the other for taking flawless aim with it. Charles Dickinson was a crack shot.

Andrew Jackson knew Dickinson before the canceled horse race had put him at odds with the lad’s father-in-law, and Jackson despised him. He had reason to. In one of those convivial settings featuring strong drink and cards, Dickinson had repeated talk about the irregular start of Andrew and Rachel Jackson’s marriage. When Andrew Jackson had first met Rachel more than a decade earlier, she had been Rachel Donelson Robards, the estranged wife of Lewis Robards. She and Jackson had married under the mistaken belief that she was divorced at the time, which was only corrected by a second ceremony after her divorce was actually finalized, an unfortunate chronology that technically made Jackson an adulterer and Rachel a bigamist. By 1806 it was an old story, but it had an enduring appeal for neighborhood gossips, and Charles Dickinson was young and callous enough to think it a suitable topic for a card table. Jackson shortly afterward cornered the lad with fire in his eyes. Dickinson had the good sense to admit he had been a cad, and his only excuse was strong drink. He apologized, and Jackson accepted the explanation and the apology, but according to Sam Houston, Jackson never forgot nor forgave the insult to his wife.

Accordingly, Jackson had reason to think that Charles Dickinson merited more notice than the pathetic Tom Swann, and when Dickinson reacted testily to the talk about his father-in-law in the matter of the canceled horse race, he re-opened a fresh wound. Not a single communication between them or their friends mentioned Rachel Jackson, but her sad shadow hangs over every step of the events that followed. After the caning of Swann, Dickinson openly blamed Jackson for impugning Erwin’s honor and did worse. He published an inflammatory notice in the Nashville Impartial Review and Columbia Repository in which he called Jackson “a worthless scoundrel, a poltroon and a coward.” Considering that a poltroon is an “utter coward,” Dickinson was making up for redundancy with emphasis, but he was dead wrong about Andrew Jackson. The notice was set to appear on May 24, but Jackson knew about it the day before it was published. The editor of The Review was one of Rachel Jackson’s relatives.

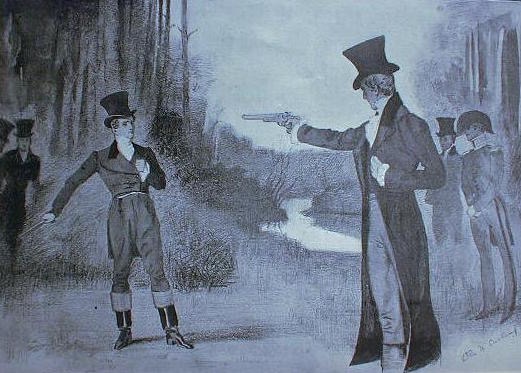

Jackson immediately sent Dickinson a challenge, and Dickinson just as quickly accepted. It took a week, however, before they met because they had to avoid Tennessee’s law that banned dueling by traveling to Kentucky. The arrangements for a place were time consuming. On May 30, Jackson and Dickinson along with their seconds and a number of companions met in a clearing surrounded by poplars as dawn broke on the Red River. Dickinson has been described as practicing his marksmanship for days, but it was curious that he arrived without a pistol of his own. They used Jackson’s with Dickinson having the choice of the pair, heavy weapons with barrels 9 inches long that took a massive ball of 70 caliber. With pistols armed and primed, they paced off a distance of twenty-four feet to separate them with pistols held at their sides. They were each to have one shot upon the signal of “Fire!” with their seconds ready to shoot down either man if he fired prematurely. After the signal, however, they could take their shot quickly or with deliberation. Dickinson’s reputation with pistols had caused Jackson to plan on careful aim rather than haste.

When the signal to fire was shouted, Dickinson immediately pulled his trigger. Jackson clutched his chest with his free hand. His legs went wobbly. He then raised his pistol slowly. Dickinson shouted in dismay, “My God! Have I missed him?” Jackson’s second drew his pistol and told Dickinson to stand still. Jackson carefully took aim for what seemed an eternity in absolute silence save for the dawn’s birdsongs. Dickinson folded his arms and stared at the gaping muzzle of Jackson’s pistol just eight yards away. Jackson finally pulled the trigger.

Jackson Takes Aim

The pistol did not fire. Instead, the hammer checked at half-cock, the position used to prime and load the weapon that rendered the trigger inoperable to prevent accidental misfires. That this happened in the poplar woods that May morning would be the source of considerable controversy later, for there would be the question of whether Jackson’s pulling the trigger amounted to his turn to fire regardless of the ineffective result. At the moment, though, Jackson simply re-cocked his pistol, took careful aim, and pulled the trigger again. Dickinson crumpled to the ground.

Both men were quite seriously wounded, but Jackson would survive to carry Charles Dickinson’s bullet in his chest for the rest of his life. It was too near his heart for doctors to remove it, and he was lucky that the fabric of his coat and shirt did not infect the wound, which was as likely to kill a man as the bullet. Dickinson was bundled up and taken to shelter where he spent the rest of the day and half of the night in terrible pain before he died. One of the last things he said was a bewildered question about who had put out the lamp. His friends standing over him sadly glanced at one another in the glare of its light.