America’s shape-shifting creature of many talents

If Americans now know Charles Thomson at all, it is most likely from the movie 1776 that was originally a Broadway musical. The show about the struggle to declare American independence has its charms, but historical accuracy isn’t one of them. Broadway veteran Ralston Hill played Thomson as fussy and purse-lipped on both stage and screen, and the show depicts him as a mere clerk whose job is to summon members of Congress for debates and votes while dishing out purse-lipped, fussy asides.

The real Charles Thomson was actually — to use a compliment of the time — a man of “considerable interests.” During the first part of Thomson’s lengthy tenure as the Congress’s secretary, the goal was winning American independence, and he was a prime mover in achieving it. By the time Thomson became the Congress’s secretary, he had for years been a patriot when it was hazardous to catch the eye of British authorities. He was a leader of the Philadelphia Sons of Liberty, and John Adams declared him that city’s version of his cousin Samuel Adams in Boston, “the life of the cause of liberty.”

He had been born in the small village of Gorteade, Maghera Parish of Ulster in the north of Ireland. In 1739, his mum died when he was 10, and his dad scooped up him and his siblings for a new start in the New World, a sensible plan until John Thomson took sick on the voyage and died just as the ship neared the Delaware Capes. There was nothing particularly unique about a child having to fend for himself in eighteenth-century America, and a mysterious woman eventually befriended him and saw to his education. Bright and diligent, Charles mastered classical languages with such facility that he earned a teaching post at the Pennsylvania Academy (forerunner of the University of Pennsylvania) when he was only twenty-one.

He also began opposing British Indian policies as early as the 1750s. The stance allied him with Benjamin Franklin, who became a mentor, and pitted him against the colony’s social and political establishment. Most of all, it earned him the admiration of the Delaware Indians, who called him “the man who tells the Truth.” He was invited to join the prestigious American Philosophical Society, whose members included brilliant intellectuals such as Franklin, the astronomer David Rittenhouse, and Thomas Jefferson.

Dark spots mottled Thomson’s life along the way. In 1758, the same year he was defending Indians and joining the Philosophical Society, he married Ruth Mather. She was a quiet, troubled young woman, and their eleven-year union seems to have ended tragically: Ruth’s grinding depression after the death of her twin babies made her a recluse and presumably suicidal. Along with other episodes, this one remains a puzzle because Thomson indulged a habit for either privacy or secrecy by burning his papers. One critical biographer concluded that Thomson had things to hide.

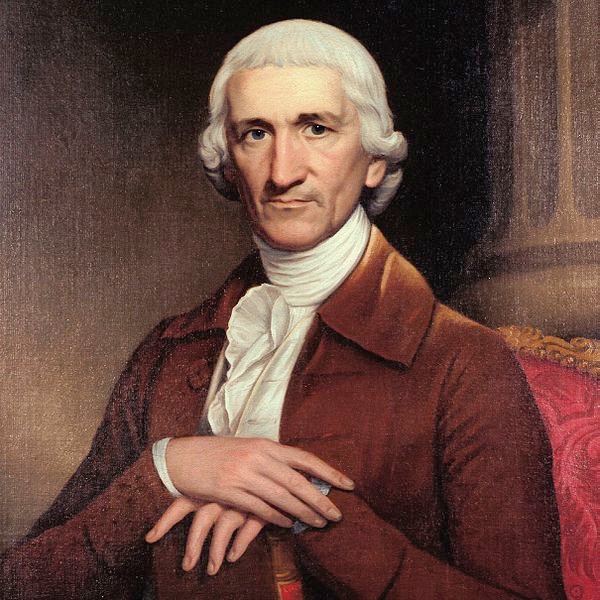

By the time Ruth died, Charles had quit teaching to try his hand at trade, iron manufacturing, and even distilling spirits. It was his second marriage to Hannah Harrison, a wealthy Quaker spinster, that allowed Thomson to commit himself entirely to the Revolution. When the first Continental Congress assembled at Philadelphia in 1775, he was forty-six years old, tall and thin, with a good voice and a confident air. His face was hawklike, a feature emphasized by his large nose (a Tory newspaper mocked him as “Old Nosey”), and he much resembled another intense patriot, Patrick Henry. Like Henry, Thomson had arresting eyes, a ready wit, yet he grew old quickly during the Revolution. His hair turned white, and he wore it shorter than was fashionable.

Charles Thomson

Thomson’s title of secretary of the Congress is misleading. He was much more than a glorified clerk. He established workaday routines and often led members through parliamentary procedures. He chose what to include — and more importantly, what to omit — from congressional journals. He drafted reports and kept all files, moving them when the Congress moved, which was often when the war threatened the government. During a tenure of fifteen years in a body that experienced a significant turnover, he became Congress’s institutional memory and thus wielded substantial influence. He was present at the creation, unique in watching both the Declaration of Independence pass and the Articles of Confederation adopted. When the Congress established the Confederation’s foreign office in January 1781, Thomson unofficially filled the position for almost a year before the actual department head took over. Europeans ranked him as one of “the great actors in the Revolution,” and the Comte de Rochambeau’s chaplain called him “l’ame de ce corps politique” (“the soul” of Congress).

Thomson also made enemies. Most members of the Congress were grateful for his labors, but an influential minority complained at what they saw as his presumption and pomposity. Thomson liked the ceremonial trappings of office and took to wearing robes during sessions, a harmless conceit but easy to perceive as putting on airs above his proper station. Thomson wasn’t shy about defending himself, either. When Pennsylvanian James Searle accused him of falsifying congressional records, Thomson charged at Searle, swinging his cane. The fight left both men bloodied.

His enemies had long memories, and Thomson barely survived several efforts to oust him from his secretaryship. He remained, lugging records from Philadelphia to Princeton and finally to New York City at the start of 1785, the one constant in a government reeling under towering debts and internal divisions. The moves were difficult, and each change of location sent him farther from his home and Hannah in Philadelphia. But he stayed on and by the time the Federal Convention met in the summer of 1787, he had become almost the only vestige of the Congress of the Confederation to remain in place. When that Congress quietly expired to be replaced by the new one created by the Constitution, Thomson did not realize until too late what was about to happen to him.

Benjamin Franklin warned him that republics “are apt to be ungrateful,” but Thomson nonetheless fancied a position modeled on Britain’s home secretary, a job like the one he had held for fifteen years but with a loftier title and a larger staff. He could see himself tending to documents, certifying them with the Great Seal (which he had helped to design), and keeping the official archives.

But gradually he took the measure of the new government and realized that his old enemies had been elected to it in distressing numbers. On the surface, he seemed confident about the situation. “It rests with them,” he wrote a friend, noting that he would retire to his farm “if they have no farther use for me.”

Beneath the surface, though, he began to marshal support to save himself from being cast out altogether. Judging his aspirations had been too high, he lowered them to the post of secretary of the Senate.

Thomson’s efforts to stay in place were thwarted, however, by his appointment to inform George Washington of his election to the presidency. The chore required him to travel to Virginia, which took him from New York while the Senate chose its secretary. Samuel A. Otis, the man Thomson's enemies wanted, gloated, “Charle [sic] ridiculously enough has got himself to go down to Genl. W. with information of his election.”

Less than seventy-two hours after Thomson headed south for Virginia, Otis had his job, and Thomson had, in Otis’s mocking words, become nothing more than the “Express rider of the Union.”

Thus it was that in April 1789 Charles Thomson took the 250-mile trip down to Mount Vernon. He officially informed George Washington of his election and accompanied the president-elect back to New York City. Nobody wanted him around after that, and Thomson retired to rural Pennsylvania to live out his days in a little stone house with Hannah. He again embraced his first intellectual love, classical languages, and labored to produce a splendid translation of the Septuagint, the Greek version of the Old Testament.

In Greek mythology, Hermes is the most accomplished guide, a shape-shifting creature of many talents, master of language and diplomacy, the luck bringer, keeper of roads and records, the most intrepid traveler, agent of Zeus, and the shepherd who gently guides the dead to the underworld. Homer hailed him as the “giver of grace, guide, and giver of good things.”

When Charles Thomson’s enemies mocked him as the “Express rider of the Union,” they were far less discerning than the blind poet of ancient, epic sagas. They could not see that the hawk-faced man of their own time was, in fact, the shape-shifting guide of many talents. Benjamin Franklin had warned Thomson about the fragile gratitude of fickle republics, and indeed, no ceremony had marked Thomson’s departure from duties he had selflessly performed during his country’s most dangerous days. It didn't matter. Charles Thomson was content to have his last service to that country be “Express rider of the Union.” The seemingly ordinary title designated something and someone very grand, very grand indeed: the luck bringer, Hermes.

He had brought George Washington to the presidency.