Inauguration Day was framed in high tension for it promised to be the last of its kind in the United States. Everything everyone had known about the country was set to change. Reports told of plots against the President-elect and that there would be an effort to prevent him from being sworn in. Rumors told of riots, and elaborate security measures transformed the capital into an armed camp.

Simple routines seemed to portend dark omens. As a military detail hoisted the flag over the Capitol dome, a halyard separated and turned Old Glory into a bedraggled kite. The mishap reminded some people of high winds toppling Charles I’s royal standard at the beginning of the English Civil War. The superstitious noted unusual celestial events. Weeks before, the northern lights had appeared much farther south than ever before. Some reports had them over Charleston, South Carolina, the place where the country had begun to fall apart in December.

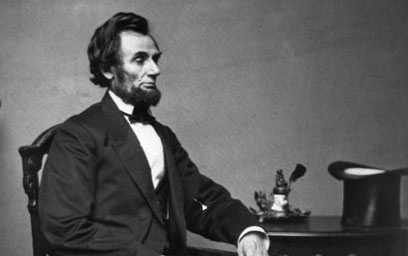

You will have perhaps guessed by now that despite some similarities to the event last Friday, these descriptions are about another Inauguration Day, the one that fell on March 4 one hundred fifty-six years ago. The sun shone on that day, but the country was in dark and dreadful trouble. The southern reaction to Abraham Lincoln’s election was unhinged from the start and gathered momentum in the weeks following it. By the time Lincoln left Springfield, Illinois for a ten-day journey to Washington, seven southern states had quit the Union.

In the face of that defiance, Lincoln’s Republican Party became more resolved in refusing to make concessions or entertain compromises. Calmer southerners in the border states, especially the crucial one of Virginia, became inflexible. Hopes that a convention in Montgomery would begin the process of reconciliation proved groundless. Instead, the convention established the Confederate States of America. Meanwhile, an assembly in Virginia was considering secession.

Only a fraying thread held that state and other border states in the Union, and it was threatening to unravel quickly. Compromise efforts in Washington either stalled in belligerent recrimination or dithered over ineffectual gestures that nibbled at the edge of the real crisis.

On February 23, Lincoln arrived in the capital and not at all ceremoniously. He stepped off an express train in the middle of the night. The plan was to foil what his escort judged a real conspiracy to kill him. Prudent as the tactic was, it was Lincoln’s first mistake since the election, and he instantly regretted it. Resolve and determination had been his watchwords on the journey from Springfield, and a calm and deliberate demeanor marked his speeches along the way. His furtive arrival in the capital went far in undermining the image he had so carefully crafted. Rather than the duly elected chief magistrate of the republic, he looked like a thief skulking in the night. He felt like one.

He resolved on the train platform that very night never to make this mistake again, even if it meant risking his life. He had plenty of other errors to make, in any case, for Lincoln himself later admitted that when he took office, he had no idea how to run the executive branch in the calmest times, let alone the stormy ones he was entering. As he settled into rooms at Willard’s Hotel, he acted composed and unflappable, but it was an act. He was churning with anxiety. He needed someone he could trust.

That someone could have been New York senator William Seward, whom Lincoln had tapped to become secretary of state. But Seward was a rival still smarting over losing the Republican presidential nomination to Lincoln. And though Seward was friendly and solicitous enough, he could barely veil his vague contempt for a man he thought not only ignorant but dense.

Seward wasn’t alone in this. When the President-elect called on Congress, many Republicans, as well as almost all Democrats, were chilly, if not disdainful. They saw in Lincoln an upstart, raw and unschooled. He looked as if he combed his hair with his hand, and his twanged regionalisms grated on sophisticated ears, especially when his grammar sometimes slipped. One unimpressed diplomat could have spoken for scores when he said Lincoln’s “conversation consisted of vulgar anecdotes at which he himself laughs uproariously.”

In such an atmosphere, Abraham Lincoln had to feel the loneliness of the presidency tenfold. Despite his habit of telling funny little stories, he was melancholy by nature and given to fits of crippling self-criticism. In those last days of February 1861, after the last visitors of the day left his rooms, he had plenty of time to contemplate his shortcomings, to weigh the sobering opposition within his party and the open hostility of the Democrats. The chief of those Democrats was a political foe of long-standing, but he was also a fellow Illinoisan who, like Lincoln, was terrified by what was happening to the country.

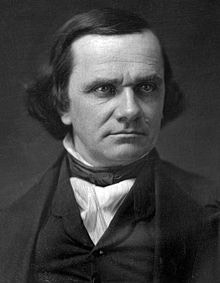

His name was Stephen Arnold Douglas, lately one of the Democrat nominees for the presidency in 1860 and thus the man Lincoln had just defeated in a bitter election. Lincoln saw Douglas when the Illinois congressional delegation called on the President-elect at Willard’s the day after his arrival. Their meeting was described as “pleasant.”

Nevertheless, Lincoln must have been taken aback by Douglas’s appearance. The man supporters fondly called “the Little Giant” had been a bantam rooster two years earlier when a series of debates between them became famous. They had vied for Illinois’ Senate seat, but the debates that had saved Douglas’s incumbency also had made Lincoln an emerging influence in the new Republican Party. It was the beginning of his path to the presidency.

At the time, Douglas had been the picture of gleaming health, confident with rosy cheeks and bright eyes, plump and buoyant and defiant. But the 1860 campaign left Steve Douglas a physical wreck and an emotional mess. When Lincoln saw him at Willard’s, Douglas’s eyes were dim and vacant. His flushed face suggested he was drinking before breakfast and well after bedtime. He was gloomy and grumpy, snapping at friends as well as foes.

A lesser man than Lincoln might have been pleased by the change. Steve Douglas had always been everything Abraham Lincoln was not. Though short in stature even for his time — he only came up to Lincoln’s shoulder — Douglas had a powerful voice that men felt in their guts and women found musical. In contrast, Lincoln’s shrill tenor reached squeaking octaves when he was excited. Douglas had regular features set off by a pronounced protrusion above the bridge of his nose that gave him a rugged, pugnacious air. Lincoln was freakishly tall and loose-jointed. A pale almost gray complexion emphasized his homely features. Douglas was graceful before the public while Lincoln was clumsy and self-conscious, sometimes flailing his arms when making a point and bowing awkwardly at applause he seemed to think he didn’t deserve.

Stephen A. Douglas

Douglas’s commanding presence had always displayed importance before he opened his mouth. He traveled on special trains, entertained lavishly, and dressed the part of the statesman. He preferred blue serge with silver buttons (gold was too gaudy), and his fine linen shirts were always crisply pressed. Lincoln rode in railroad coaches on regular trains where he chatted up fellow passengers who often thought him an odd duck. He dressed plainly in wrinkled shirts and drab frock-coats with sleeves too short and frayed trousers with cuffs that barely reached his ankles. He would not have disagreed with the description of him as “a cross between a sandhill crane and an Andalusian jackass.”

Steve Douglas knew better than this. His long acquaintance with Lincoln taught him that the shabby clothes and shambling manner were partly a pose but mainly a reflection of temperament. He also knew that though Lincoln made fun of himself, he was at heart a proud man who privately detested the “hick stuff,” the rail-splitter image, the overplayed “honest Abe” bit, the contrived stories of how he came by his knowledge through backwoods wisdom rather than thorough study and extensive reading. More important, Douglas had found out the hard way that Abraham Lincoln was not stupid, and he sourly appreciated the way Lincoln’s awkward charm could warm hearts and change minds.

They knew each other too well. Douglas had never liked Lincoln, and Lincoln had returned the feeling, sometimes revealing a streak of jealousy over Douglas’s success and status. Lincoln thought Douglas had purchased success with political favors and had sustained the status with phony airs and silly posturing. The 1860 election had not helped matters.

But their reunion at Willard’s had been pleasant, and when Lincoln visited Congress, the frosty reception was broken by Steve Douglas shouldering through to shake Lincoln’s hand and show him around. Douglas glowered at reluctant politicians and thus forced his colleagues into a strained civility. Douglas’s wife — the beautiful New Englander Adčle Cutts who set social trends in the capital — very publicly called on Mary Todd Lincoln and made certain that others would follow her lead.

Such gestures eased the way for these two men to have a private conversation. They arranged it for the night of February 27.

Douglas did all the talking while Lincoln listened, his eyes somber and hooded, his face expressionless. Douglas urged Lincoln to action, first to prevent further damage to the Union by conciliating the border states. Then the government could begin mending the damage already done. Douglas assured Lincoln he would not obstruct the administration for partisan advantage, and he would use every particle of his influence to make the Democratic Party behave itself while the new President tried to save the country. “I am with you, Mr. President,” Douglas pledged, “and God bless you.”

Lincoln thanked him, and they parted. Douglas was disappointed that the President-elect had not been more talkative. He had no way of knowing what Lincoln had exclaimed to another visitor after the meeting.

They did not see each other again until Inauguration Day. The pageantry ordinary for such occasions was peculiar and incongruous on this one given everyone’s edginess, and the sobering ubiquity of soldiers mounted and on foot. A battery of artillery ominously sat north of the Capitol. Sharpshooters peered from rooftops along the route from Willard’s Hotel to the Capitol. Others poked their rifles out of the Capitol’s windows, ready to take aim at any assassins in the crowd of some 25,000 spectators.

After the short carriage ride from the hotel, Lincoln and President James Buchanan entered the Capitol through a plank and boarded enclosure, a design to deprive a sniper of a clear shot. When they walked out on the wooden platform on the Capitol’s east portico, the politicians, Supreme Court justices, and diplomats already assembled offered up a smattering of nervous applause. Lincoln, or someone, had used a comb on his hair, and he was sporting a new suit that fit him for a change. It had been tailored for his irregular frame. He carried an elegant ebony cane, also new, that revealed an uncharacteristic extravagance by way of a large gold head. He wore a shiny silk hat called a “stovepipe” for its resemblance to an oven’s chimney.

March 4, 1861

As Lincoln took his seat on the platform, he clumsily coped with these fashionable accessories. The cane and hat were one too many. When he removed the hat, he fidgeted, shifting it and the cane from one hand to the other. He tried putting the hat on the platform, but people seemed oblivious and were sure to trip over it. He picked it up and put the cane down. The hat thus remained a problem, and as his friend Sen. Ned Baker began introducing him, Lincoln discovered it wouldn't fit under his chair. A reporter for the Cincinnati Commercial looked on with considerable amusement. Later he would write it all up as “a funny incident” of the inauguration.

Baker was concluding his remarks. Lincoln stood and approached the rostrum, the hat still in hand. He juggled it while reaching for his speech. It was then that Steve Douglas, who had been watching the President-elect, left his chair and quickly walked to Lincoln’s side. “Permit me, sir,” he muttered. Douglas took the hat back to his chair and held it in his lap while Lincoln delivered his inaugural address.

Lincoln placed steel-bowed glasses on his nose, pulling the earpieces back through his thick hair. A ripple went through the surprised crowd. None of his pictures had shown him wearing spectacles. The high tenor then sounded the words. Buchanan sat with his eyes closed, and others frowned. Douglas watched intently, hanging on every phrase. “I do not consider it necessary,” Lincoln said, “. . . for me to discuss those matters of administration about which there is no special anxiety or excitement.” He proceeded instead to promise southerners that the government would not endanger “their property and their peace and personal security.” He begged southerners to pause, to consider, to take the time to reflect. “In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine,” he declared, “is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you.”

The speech was almost four thousand words long, but even so, at the end, he was “loath to close.”

“We are not enemies, but friends,” he said, and implored, “We must not be enemies.”

And then: “Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

Douglas had heard that piping voice enough to know its cadences when striding toward a conclusion, and he was setting down the hat to applaud vigorously as Lincoln said the final words. Lincoln then took the oath of office administered by the withered Chief Justice Roger Taney, just days shy of his 84th birthday and the author of the infamous Dred Scott decision that worked to fasten slavery forever on the land as judicially endorsed law. And thus Abraham Lincoln became the sixteenth President of the United States. How far his executive reach extended in the fragmenting republic remained much in doubt.

The uncertainty, in fact, was painfully evident by the mixed reaction to Lincoln’s inaugural address. The North had varied impressions. One Democrat newspaper dismissed it as a “rambling, discursive, questioning, loose-jointed stump speech” and lamented how the first act of the Lincoln presidency had been reduced to a campaign event. But that was high praise in comparison to the speech’s reception in the South. There it was perceived as a declaration of war. All opinions, whether good, middling or bad, proved the fact that the plainest words cannot penetrate the prejudices of any given audience.

For his part, Steve Douglas was appalled by northern criticism of and southern anger over Lincoln’s clear statements. Two days after the inauguration, he delivered a speech to the Senate heatedly declaring that anyone who found ill will in Abraham Lincoln’s address was deluded. Douglas insisted that the President intended to preserve the peace. Unionist members of the secession-leaning Virginia Convention asked him, “Is there any hope for us? Can we remain in the Union?” Douglas answered, “Yes, there is hope. Stand firm and all will yet be right.”

Perhaps Steve Douglas thought it would be so, but it’s likely that Lincoln already realized it could not. In the weeks following the inauguration, the federal forts in the seceded South became an unmanageable issue. Douglas hoped until the end that Lincoln would buy time by removing federal troops, but he understood why that could not happen. And when the first shots were fired in Charleston over the fate of Fort Sumter, Douglas did not waver. He called on the President to renew his pledge of support. Lincoln had issued a proclamation calling up 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion. At their meeting, Douglas disagreed only to the extent that he thought it should be 200,000. He expressed that kind of resolve to every Democrat and Republican he encountered.

At the end of April, Douglas left Washington to carry the message of Unionism to a special session of the Illinois legislature. He intended to rally Democrats in the region “in favor of the Union” and then return to the capital. He achieved the first goal, but public appearances and speeches in Springfield and Chicago consumed more energy than he had to spend. By mid-May, he was bed-ridden with a high fever. He assured his worried family that he would be up and again fighting for the Union in no time, but his doctors traded glances at such talk.

Stephen A. Douglas died at 9:00 in the morning on June 3, 1861. He was 48. The telegraph instantly brought Abraham Lincoln the news, and he promptly closed all but the most essential government offices. He had cause to reflect on their February meeting when Douglas had told a lonely man that as long as Steve Douglas drew breath, Abraham Lincoln would never be alone in the struggle to save the country. Lincoln had reason to remember what he had exclaimed to a visitor afterward: “What a noble man Douglas is!”

They had known each other too well. But only at the end, when it really counted, did they understand.