It is strange that George Washington began his most ambitious remodeling of Mount Vernon as relations with Great Britain grew increasingly bad. Artisans would be scarce and importing materials would be made difficult by boycotts, or worse. Nevertheless, when it was done, Mount Vernon was to stand as the world now knows it, a house both stately and intimate, with grounds landscaped to display its charming setting. It turned out that way because of someone many people have never heard of.

Washington knew that his plans were elaborate, but the difficulties of the project were beyond his imagination. He planned to enlarge the house substantially by extending each side for a total of 44 extra linear feet. The increase in square footage would allow for a large study on the ground floor of the house’s northern side with a bedroom above it. Both of these new spaces were to be quite private with access to them restricted to small vestibules placed on the western wall. A hidden staircase led up to the bedroom, or “Mrs. Washington’s room” as it was always called, despite their sharing it.

On the other, or southern, side of the house, Washington planned to add the largest room of the structure, a true hall two stories high that was at first simply called “the New Room,” a name that stuck. Ornate, spacious, and fitted out with a triple-arched window in the Venetian style, this was to be a grand room, the most formal space in the house where special events such as large parties and family weddings could be held.

The project began in the fall of 1773, and because tensions with Britain were by then in crisis, George Washington was summoned away from Mount Vernon soon after, first to Philadelphia for the Continental Congress and afterward to Massachusetts to take command of the Continental Army. He would not again see Mount Vernon for six years and then for only a flying visit. In the end, he would not return to stay until the end of 1783. Washington had to depend on someone to continue the work from its infancy.

That person was a kinsman named Lund Washington. Lund was always reliable and even exceptional on occasion, both in his management of the farms and in his direction of the house construction. He was also a faithful correspondent whose regular reports comforted Washington as he fought the war in Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania. Lund responded quickly to queries and carried out instructions with persistence and attention to detail that at least came close to how Washington himself would have attended to the project.

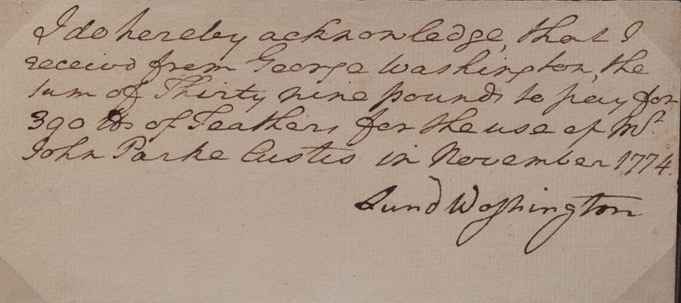

Lund Washington was always exceedingly careful with other people’s money.

Lund Washington was a descendent of George Washington’s great great uncle, and though his forebears were less prosperous, Lund was not penniless, just unpropertied. Before working at Mount Vernon, he managed extensive plantation operations for several prominent Virginia families, experiences that made him a capable husbandman, if not a builder. He was unassuming and had not a shred of pretense or guile. He was unshakably jovial as events would prove, his temper rarely getting the better of him. Because he was family, Lund lived in the mansion house rather than a separate building during his time at Mount Vernon.

That time began in 1765, making his tenure already a decade old by the time Washington took command of the Continental Army outside Boston. Lund had been an able assistant during that time, and while Washington was away, Lund took on a host of added responsibilities that essentially made him the master of the estate and all its operations, including the extensive remodeling project that Washington was determined to see carried on, come hell, high water, or British invaders.

Again, nothing in Lund’s experience had prepared him for this daunting task made all the more difficult by wartime shortages of men and materials. He took many things on himself and must have wondered over the wisdom of spending sweat and treasure on a house that British marauders could at any moment turn into a smoldering foundation. He fretted about this more or less constantly and even came up with a plan to blockade the Potomac below the mansion, though nothing came of it.

George Washington’s expectations were always high and seldom unexpressed. He could be more solicitous toward Lund because he was family, but Washington could be stern with employees who displeased him, and in the end Lund was an employee as well as family. He discovered it was easy to disappoint George Washington. When the Royal Navy vessel Savage glided up the Potomac in the spring of 1781, Lund’s concern for Mount Vernon’s physical security prompted him to treat the British as guests lest they become vandals. He gave them refreshments, kind words, and provisions, certain that it was a small price for their uneventful departure. Lund was not a coward, but he was so naturally pleasant that rudeness could make him physically ill. Washington frequently complained about Lund’s reluctance to demand that chronically delinquent tenants pay their rent, but he also realized it was not in Lund’s nature to be forceful with forlorn people. The hospitality shown the “parcel of plundering Scoundrels” from HMS Savage, however, mortified Lund’s employer. Washington said he would have rather they had burned the place to the ground.

Under trying circumstances, Lund’s work on the house proceeded at a relatively remarkable pace. While Washington was outside Boston facing down the British occupation there, the southern wing for the New Room neared completion, and as the months passed in the late 1770s, Lund also kept busy building and rebuilding more functional parts of the estate, such as the wash house, schoolhouse, tool sheds, and garden enclosures. He seemed much more comfortable with these chores. In 1778, the graceful semicircular colonnades were erected to link outer dependencies to the main house, but Lund worried that they were not what Washington wanted. In this case as with other matters, Lund did what he could when his preoccupied employer did not make himself clear.

The spacious piazza on the river side of the house was added at this time as well, the elevation of its floor from the Potomac a precise 124 feet, 10-1/2 inches. This addition was simply a stroke of aesthetic genius that became the most popular place at the mansion. By extending the house’s roof and supporting it with eight simple and surprisingly delicate columns, the plan avoided the impression of massive weight that could have overpowered the house and spoiled the effect. From the piazza the view was impressive, river breezes were soothing, and numerous green Windsor chairs invited family and guests to relax. They still invite visitors at Mount Vernon to do the same.

Mount Vernon’s river frontage features the charming piazza that Lund began during Washington’s absence.

The two instances of the New Room and the piazza showcased the problems of Lund’s otherwise conscientious supervision. The New Room remained a work in progress for almost a dozen years as trouble with artisans and materials plagued the project. Washington had been home from the war a full three years before it finally neared completion. And like the New Room that seemingly refused to be finished, the piazza was an evolving idea for years. As late as 1786, Washington chose to replace its surface with new flagstones, possibly because Lund’s choice of material did not please him, or possibly because the originals had suffered frost damage.

Even if much remained to be done when George Washington returned home on Christmas Eve in 1783, Lund’s efforts had worked a set of minor miracles, something that Washington became acutely aware of when Lund left in 1785. For twenty years, this good man was his companion in the enterprise of Mount Vernon and for almost half of that time, he was the outright manager of its operations. He had married Betsy Foote in 1779, a deeply religious woman as kind as he, and they lived at Mount Vernon while he built a house on a parcel of land that Washington ultimately gave to him outright. It was a generous gesture but entirely appropriate considering that Lund Washington had proved unique in George Washington’s experience. Lund had never asked for more than his due and was often willing to do with considerably less. He never trafficked on his cousin’s fame. He never tried to use any influence derived from his intimate association with his famous relative.

Washington appreciated this even if he didn’t always show it. At the start of his long absence from Mount Vernon, he told Lund that he hadn’t the slightest doubt of his “Integrity.” For George Washington that was praise so high it would in a long life be settled on very few people. True enough, in the years that followed, Washington could be stern and hectoring with Lund, but he freely admitted that Lund’s work at Mount Vernon had allowed him to give “not only my time but my whole attention to the public concerns of this country.”

Only months after George Washington wrote these words, Lund and Betsy settled into their new home at the modest farm he named “Hayfield.” Their two daughters had died many years before in their cribs, and Lund was going blind, but they lived simply and happily, bolstered by Betsy’s piety and Lund’s unfailing good cheer. They resided only about four miles from the man Lund loved as a brother and had selflessly served through all weathers and difficulties, season upon season, while the grand house above the river was transformed from a plan to a reality. In many ways, that house was a monument to George Washington’s distant kinsman, the man who gave without keeping a ledger, who always took less than he gave.