Citizens of New York prided themselves on having seen everything, but they had never seen anything like what was happening in their city that summer of 1790. For three weeks, the nation’s capital — which New York was at the time — was playing host to a delegation of bona fide exotics, twenty-seven in number and committed to achieving something not only unprecedented but extraordinary. Everyone agreed that it would be wonderful to have it work out.

The guests were Creek Indian headmen representing their confederation to the United States government. That simple description, however, doesn’t do justice to the momentous nature of their purpose. In the first place, the very idea of such a confab was more than novel. It was the first such meeting of its kind, and the newly created American government was not just willing to treat with these Indians but was taking pains to treat them with diplomatic decorum and solemn respect. The cynical view that dismisses every situation wherein whites claimed to negotiate with Indians as simply another instance of white duplicity and Indian victimization entirely misjudges what was happening in that remarkable summer of 1790.

That July and August the Creeks and their American hosts conducted serious, meaningful negotiations day after day, bargaining over this concession or standing firm over another. The Creeks often appeared impassive, as was their way, even when trading sidelong glances that sometimes meant consent or sometimes signaled refusal. Chief American negotiator Henry Knox as secretary of war at least symbolically matched the warrior ethos of his guests, but Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson was also participating, providing proof that these were diplomatic talks between equals on the highest level. There had been no war to force a capitulation. In fact, the project’s main objective was to preserve the peace. Because President George Washington had made clear that he regarded the success of these talks as crucial to the health of the new constitutional republic, the Americans well knew what was at stake.

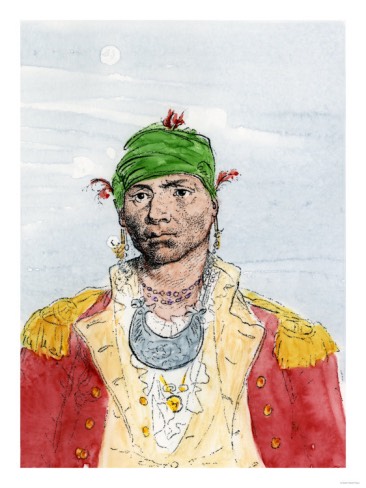

One man in two worlds, Alexander McGillivray was the son of a Scot. He was also the child of Sehoy of the Wind Clan and known as Hoboi-Hili-Miko, the “Good Child King” who became the Great Beloved Man.

Negotiations proceeded with everybody understanding everything because the head of the Creek delegation spoke perfect English and flawless Muscogee. His name was Alexander McGillivray, a moniker that provides a clue to his facility in sorting out the cultural as well as the linguistic challenges accompanying the negotiations. He was the son of Scottish trader Lachlan McGillivray and Sehoy, the daughter of a French officer and a Creek woman. His parentage made Alexander only one-quarter Creek, but Sehoy belonged to the powerful Wind Clan, and Creek matrilineal tradition made her son influential from the start. As he grew up, he expanded that influence to include the white world as well. His Indian kin regarded him as a natural born leader in the literal sense of the phrase, but whites respected his poise and aplomb. Educated in Charleston and apprenticed in Savannah, Alexander McGillivray returned to his mother's people to manage a plantation and own slaves with a sound understanding of the way the universe worked outside the bounds of the Indian world. Planter squire, power in Creek politics, highly intelligent planner, and careful schemer, McGillivray gradually became something resembling an emperor in the Creek Nation. He was not yet forty, but Creeks called him the “Great Beloved Man.”

Alexander McGillivray never liked Americans. He inherited the animus from his father, who had been a Loyalist during the American Revolution. Afterward, Lachlan McGillivray returned to Scotland and gave his Creek country plantation and its slaves to Alexander, but the family’s ties to the British gave Georgia an excuse to confiscate the property. That injury stoked Alexander’s hatred of Georgians and encouraged him to court favor with America’s enemies. He parlayed with the Spanish in Florida and did business with the British firm of Panton, Leslie and Company in Pensacola. It was easy for these people to ingratiate themselves with McGillivray. The merchants wanted only cash on the barrelhead; the Spaniards in Florida wanted only a buffer between their imperial outpost and upstart Yankees seemingly intent on expansion.

In short, the British wanted the Creeks’ business, the Spaniards wanted them as a counterweight, but the Americans wanted their land, and that desire literally grounded in real estate caused all the trouble. The Creeks were a sedentary people who lived in towns where the women practiced subsistence agriculture while the men ranged to hunt. The latter tradition made them proprietary over enormous spans of acreage, but the horticulture anchored them to specific places on the land, places that were centuries old with venerable names. The state of Georgia, however, had developed a deplorable habit of selling Creek land it didn’t own to speculators who, in turn, sold it to American settlers who were steadily moving deeper into the wilderness. The Creeks were at first nonplussed but eventually resorted to violence to evict the interlopers, and the beleaguered settlers appealed to state and national governments for protection.

If war broke out between Americans and Indians in the South, the fragile arrangement of the new Constitution would be sorely tested. The United States government would be compelled to support Georgia in such an extremity, or the Union would be shattered and the American experiment stillborn. The sensible plan was to avoid an immediate war, but George Washington and his advisers wanted an enduring solution to what they called the Indian problem, what the Indians would have rightly called the settler problem. That uncompromising appraisal of the “problems” resulted in a remarkable burst of optimism that seemed to defy reality: a rational program that would secure the country by making the Creeks neighbors rather than adversaries.

How was this to be done? Henry Knox had long dreamed about assimilating American Indians into European-American culture through a “Civilization Plan.” The government would set up schools to teach Indian children English and the rudiments of white culture. American representatives would become extension agents to promote farming over hunting. Donations of domesticated livestock would smooth the transition. Farming would require less land than hunting, and Indians could sell their excess acreage to the government, which could then superintend orderly settlement that wouldn’t expose pioneers to Indian hostility. Indians would not feel cheated and have no reason to harbor hostile feelings toward their new neighbors. Such a frontier would require a much smaller (and less expensive) military for it would become a place of the corn shucking festival, the barn-raising, and eventually the Creek boy would be calling on the comely girl in the settler’s cabin or the pioneer lad finishing his chores would go courting in the nearby Creek village. The Romans had done something like this as they had expanded as bringers of peace, with the result that friendships became families as soon as people discovered themselves all to be people.

Thomas Jefferson liked the idea immensely, and George Washington was more than intrigued by it. Knox championed the plan with verve, and Washington was caught up in its allure, especially since it embraced Enlightenment ideals of rationalism, improvement, and equal treatment as natural right. After all, the only alternative was to force Indians from their lands and kill those who wouldn't leave. The happy dream of harmony through shared customs stemmed from the best of motives, and little blame can be attached to anyone wishing for a better world. President Washington invited Alexander McGillivray to bring a Creek delegation for direct talks in New York City, not as a defeated foe but as a potential partner in a grand undertaking. Americans knew McGillivray was angry and that he had cause to be, but they also knew him as worldly, and they had every hope that open-minded negotiations would appeal to this cosmopolitan Creek leader who, it was said, studied Latin and read John Locke for pleasure.

Alexander McGillivray was not a sentimental sort, and he did not come to New York because he changed his mind, let alone his heart, about Americans. Rather, this hardheaded realist had heard rumors that Great Britain and Spain were on the verge of war. Possibly the stories about his knowing Latin and quoting Locke were mere fables, but he certainly knew about imperial pride and the European way of war. He sniffed the air, detected the slightest trace of gunpowder in shifting European fortunes, and decided it was a good time to talk to the American government.

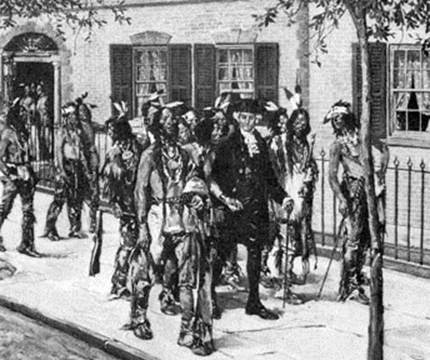

So it was in that propitious summer that he and twenty-six Creek headmen set out for New York City accompanied by an army escort, McGillivray in a stylish carriage and the other Creeks on horseback. As they traveled through Georgia and up the coast, something was in the air. Communities turned out for the exotic sight of important Indians in peaceful procession, but receptions did not stem from curiosity alone. Town fathers showered the Creeks with platitudes of fealty and friendship, and citizens smiled, waved, and blessed their purpose. It was a mere prelude to New York City’s open arms and warm greeting.

The government arranged for the Creeks to lodge at a fashionable tavern, and Knox had McGillivray stay at his home on Broadway. The pace of negotiations that soon got under way suggested neither urgency nor haste as Knox and Jefferson made their proposals, the Creeks listened, countered, contemplated, and finally consented. In the agreement that became the Treaty of New York, the Creeks agreed to give up land that Georgia had already taken, and the United States pledged to pay them an annuity, which amounted to a purchase but also carried an unspoken but obvious apology for the theft. The United States did not object to the Creeks continuing their trade relations with Panton, Leslie and Company, and formally exempted such trade from tariffs and duties. If anything interrupted commerce with that, the United States would supply Creek needs.

At the center of the enterprise, however, was the first sign that something was vaguely wrong. To be sure, the treaty included references to Knox’s civilization program — mainly clauses about schools, agriculture, and livestock — but nobody made too much of this, which suggests that the idea had not been greeted with enthusiasm despite its initially being the heart of the project. McGillivray does not seem to have troubled himself over the cultural implications of this section of the treaty, and Knox apparently considered it wise to not put too fine a point on it. He, Jefferson, and Washington preferred to believe that all would come ‘round right in the fullness of time. McGillivray seemed to hope that he had found another partner to play against his Spanish and British ones.

The exotic visitors from the South fascinated even jaded New Yorkers.

At the end, on August 7 an imposing signing ceremony in the Senate chamber and a celebratory banquet afterward held all the promise of a bright future, and there is every reason to believe that every one of these people sincerely hoped that what they had worked on would work out. Yet in retrospect, it is hard to imagine how they could not have known that they had made promises none of them could keep. The men in the American capital were a thousand miles away from the Creeks’ homeland and could not possibly control the surging populations that would soon rush into their fertile hunting preserves; the adoption of white agriculture would deeply divide the Creek people and pit opposing camps of nativists against those they called accommodationists, an attitude that did not sow corn but civil war. Such a conflict would shatter the Creek Confederation in less than twenty years. When these realities came to light, both sides came to the worst possible conclusion: that their counterparts had acted in bad faith, that Creek passivity had been a mask for duplicity and American enthusiasm had been a crafty con job. It was the foundation for bad feeling and incurable wounds.

Yet in those three weeks of that summer, the social whirl had suggested a better world on the way. The St. Andrew’s Society celebrated McGillivray’s Scottish ancestry by making him an honorary member. The Tammany Society held a festive event for all the headmen. The Creeks fascinated the ladies of New York, and a headman conferred on Abigail Adams the name “Mammea,” as he took her “by the Hand, bowd [sic] his Head, and bent his knee.” The vice president’s wife had moved in the finest salons of Paris and the most fashionable parlors of London, but she had never seen anything like it nor been so moved by an honor. It had moved the Indians too, who shed some of their impassivity as the days wore on. The artist John Trumbull showed them his recently completed portrait of George Washington, and rather than pretend indifference they openly marveled at how a flat image could convey the impression of depth and perspective. Nobody thought them odd or backward for this, any more than the Creeks would have mocked Trumbull for not knowing how to find his way in a trackless wilderness by scent and sensation.

That was real progress, after all, and from that it’s perhaps easier to see how everyone could have been so hopeful. Despite its sad fate, the Treaty of New York was an impressive agreement in its attempt to set a new tone in relations between different peoples living under a new political order. Everyone at least acted as if they realized this during New York’s Indian summer, but when the Creeks headed home, they closed an episode that would never be revisited the same way and in the same spirit by any other Indians in America. They traveled south by water down to the coast of Georgia and then overland to their homes, perhaps to wonder how much they had protected those homes. The tall man called George Washington and his stately advisors had spoken kind words and uttered seeming truths, but those men were a thousand miles away. The Creeks returned to a place where settlers were still yoking their wagons to drayhorses and running thumbs along the sharpened edges of axes.

The Great Beloved Man, who was never sentimental, probably knew the truth of it. Apart from his immense talent, he was an alcoholic being used up by illness. He died less than three years after the grand procession and great ceremony of the treaty that was supposed to protect his people while guaranteeing their integration into the white community. Henry Knox and Washington continued to wish for a world of peace and harmony, and it would have been lovely if only it could have been so, but they were a thousand miles away.

Alexander McGillivray probably knew the truth of it. In the days remaining to him, he could hear the sound of pinging axes in the distance, coming nearer.