Seth Thornton didn’t look like a soldier. He was small in stature, thin to the point of wiry, and took sick at the drop of a shako hat, but he was nothing if not game. Indeed, an impetuous streak in Thornton made men serving under him nervous about his rashness but glad to be around courage when it counted. Superior officers liked him enough to overlook his occasional lapses in judgment and occasional disregard for details because they knew when danger loomed, Seth Thornton was anything but a small man with a spare frame. The soft voice could boom commands, and the little body swelled to a commanding presence. People who had seen this happen thought it something akin to shape-shifting sorcery.

Take what happened on the SS Pulaski for just one example. He was aboard the steamer that afternoon in 1838 as she was happily churning down the North Carolina coast. Then her boiler blew up and set the decks on fire. The explosion shocked everybody into momentary inaction before the flames threw all passengers and much of the crew into panic. Seth Thornton calmly walked the slanting deck, shouting orders, shoving women and children into lifeboats, and standing with arms akimbo and eyes surveying the chaos until there was nothing more he could do. He then tied himself to the nearest thing that could float — a hen coop was the best he could find — and hurled himself in the water as the Pulaski vanished below the surface. Thornton wasn’t through, though. He came across a few men flailing the water. He calmed them down before tying them to his hen coop. They drifted for days like that, dying one by one, except for Seth, the frail one. A boat found him still tied to the chicken coop, a little bag of bones with a blank stare, shouting incoherently and most certainly about to die.

Seth Thornton wasn’t through, though. Fished out of the water and brought ashore, he survived and reported for duty in Florida where the army was fighting the Second Seminole War. By the time of the Pulaski disaster, Thornton had been in the army for two years as a third lieutenant appointed by President Andrew Jackson, which made the young officer part of a controversy at the outset of his career. Regular officers educated at West Point resented the intrusion of amateurs like Thornton, and they fumed when the upstarts received promotions. Thornton didn’t let it faze him. He was a Virginian by birth, a Caroline County man, who knew his worth but kept quiet and let his behavior, rather than his manner, convince his detractors. A bit of sniping at him with muttered complaints wasn’t his biggest problem in any case. The Seminoles tried to kill Seth Thornton several times but couldn’t. Yellow fever took a crack at him but managed only to lay him low for a spell. When he bounced back he looked like death warmed over, but his jaw was set, his shoulders squared, and he sat his horse with only a hint of a weave and a wobble. West Point men noticed all this, and when Set Thornton became a captain of the 2nd Dragoons in February 1841, they didn’t complain. They smiled and nodded.

Five years later, Thornton was still a captain, but that wasn’t a reflection on him. The army’s officer corps at all ranks had a limited number of billets that were filled with aging occupants stalled at captaincies, majorities, and colonelcies. At 33, Thornton was a relatively young captain as he served on the Rio Grande as part of General Zachary Taylor’s ambiguously named “Army of Observation,” but he was about to become a household name all over the United States.

Taylor’s command was oddly styled as observational because it was supposed to be watching the disputed ground between the Rio Grande and the Nueces River some fifty miles to the north. Who owned the real estate was an old argument that had started a decade earlier when Texas gained its independence from Mexico, and the recent annexation of Texas by the United States had made the question more than an argument over geography. By the spring of 1846, President James K. Polk was provocatively rattling General Taylor’s saber, and Mexican president Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga was finally provoked. He proclaimed that Taylor’s “occupation” of Mexican soil merited a state of “defensive war.” He sent General Mariano Arista to Matamoros just across the river from Taylor’s encampment with orders to drive the invaders from the Rio Grande Valley. Arista accordingly sent General Anastasio Torrejón with 1,600 cavalry across the river to cut Taylor’s supply line to the Gulf of Mexico.

Taylor’s Army of Observation was at last required to live up to its name and observe something. Increased activity across the river prompted Taylor to find out if the Mexican army was moving to his east toward the gulf or to his west on the Rio Grande. He sent out two patrols accordingly. On April 24, he ordered Captain Seth Thornton to command the one probing west, and after camping a ways out from the Taylor’s main position that night, Thornton had the 63 men of Companies C and F of the 2nd Dragoons on the move early next morning. He didn’t expect to find anything. Isolating Zachary Taylor by cutting his communications with Port Isabel meant the Mexicans would cross between Taylor and the Gulf, meaning to the east. As Seth Thornton headed west, he didn’t expect to find anything.

That was one of the reasons he didn’t send out riders to protect his flanks or place a trailing party to act as a rear guard. His advance party consisted of ten men about a quarter of a mile ahead of his column with orders to fire shots if they saw anything and fall back immediately to rejoin the main body. Those orders seemed pointless, though. The winding path that followed the river was so hemmed and blocked by dense chaparral that Thornton and the main body kept stumbling on their own point men. That, the terrain, and the casual disorder of the ride westward began to make Thornton a trifle uneasy.

It was bad country for mounted men. The thick chaparral kept them in single file, strung them out, kept them blind. Around 9:00 that morning, as they were jumbling up again with the advance party, the column paused at a clearing and saw someone in the distance who shouldn't have been there. It was a man on horseback. He was staring at them, but he abruptly wheeled and spurred his horse to disappear at a gallop. They pressed on and came upon a few small adobe houses. The guide accompanying the reconnaissance talked in whispers to the Mexican residents for about ten minutes. He returned and told Thornton he wouldn't escort him any farther. The captain was by now more than a trifle uneasy.

He paused to swallow and then calmly made his way to the rear of the column where he spoke to a fellow captain named William J. Hardee. He quietly warned Hardee they were likely to be attacked. He then moved along the column telling the men to unsling their carbines.

They continued westward along the river until they came to a large plantation. Thornton wanted to enter it to seek information, but it was surrounded by high chaparral, and only after riding along the natural fence for a distance could he find a small opening. He brought his men into a field enclosed by chaparral. It was about 300 acres in area and itself a maze of chaparral fences. As a few Mexicans appeared from small adobe lodges, some of the American dragoons dismounted to fill their canteens from wells and stretch their legs. Thornton approached an elderly Mexican and asked if there had been any soldiers in the area.

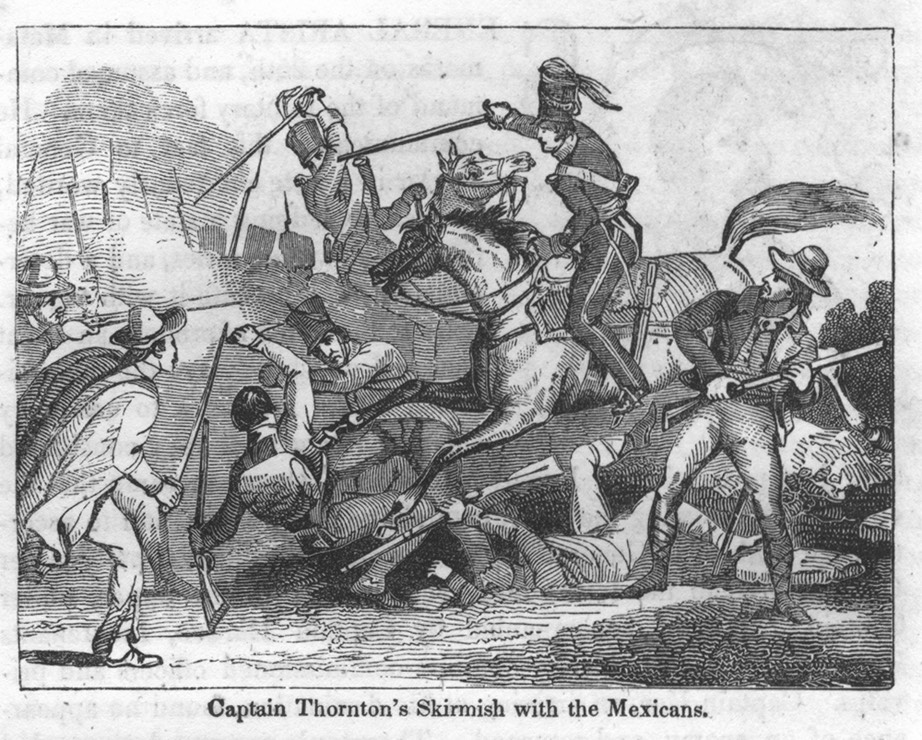

It was then that Thornton heard the unmistakable thwack of a bullet striking ground nearby and instantly after it the pop-pop-pop-poppoppoppop of gunfire coming from the chaparral fence several hundred yards away. Seth Thornton swung into the saddle and unsheathed his sword. He shouted, “Charge!” and galloped at full tilt toward the invisible attackers. The dragoons still mounted jerked their reigns and spurred their horses to follow, and those on the ground tumbled over one another trying to find their stirrups. They were following the little captain with the quiet voice who had suddenly, inexplicably transformed into a small giant in the saddle with a shout that they felt in their guts.

Even so, it wasn’t a pretty charge from a story book. Caught by ambush, the men of the 2nd Dragoons did the best they could to make a fight of it, but Seth Thornton’s charge was quixotic in the truest sense of the word, including its absurdity. Torrejón had three times Thornton’s number drawing aim and taking potshots from the chaparral. He had been trailing Thornton’s column for miles with 500 additional men and some 150 Indian allies. The balance of his force of 1,600 stood ready to cut the Americans to pieces if necessary. Torrejón had not crossed east of Zachary Taylor but west of him, where he shouldn't have. He had crossed where Seth Thornton knew he wouldn't. Until Seth Thornton heard the thwack.

The little roan under the little giant took a bullet and plunged to the ground, catapulting Seth Thornton into the chaparral where his men knew he was dying, if not already killed. Hardee riding hard to the scene tried to organize a retreat, but for these men taking fire on all sides falling back was an instinctual urge that added to their confusion. The thwacking bullets hitting men in legs and abdomens, horses screaming in agony, and a milling about in the middle of a large and lethal field could only last so long. They surrendered. It was a miracle that only eleven of them were dead and only six wounded. The Mexicans took the unscathed as prisoners, and Torrejón gallantly sent the wounded to Taylor because he didn’t have a way to care for them.

For a couple of weeks, Americans thought Seth Thornton was dead. Polk sent a war message to Congress, and the United States declared war on Mexico as a direct response to the “Thornton Affair,” as the newspapers called it. But just as the exploding Pulaski, Seminole Indians, and yellow fever couldn't kill Seth Thornton, the ambush at Rancho de Carricitos couldn’t either. He was among Torrejón’s prisoners, if a bit worse for wear. He, Hardee, and other officers and men were taken to Matamoros where Arista was kind, hospitable, and so solicitous that Seth Thornton and William Hardee would never forget the grace and would not tolerate a hard word spoken against their enemies. And when Thornton was returned to Zachary Taylor as part of a prisoner exchange in May, the newspapers rejoiced over the reports that he lived, making him a legend that would have made Don Quixote himself envious.

In a way then, the war that followed the events of 170 years ago on that April 25 was Seth Thornton’s war, even if its opponents would denounce it as “Polk’s War.” As he had stood firm in Florida, Thornton would not knuckle under to misfortune or illness, though both continued to stalk him in Mexico as a sort of theme of his life. “It seems,” said one of those admiring newspaper reports, “he is not to be killed by accidents of flood or field.”

As the American army began its final push toward Mexico City in the summer of 1847, Captain Thornton was ill abed, but he pulled himself up on a horse to lead another reconnaissance of his 2nd Dragoons. They were scouting outlying Mexican positions as an artillery battery far in the distance was muttering, its location so remote that only the telltale little puffs of smoke disclosed it as the source of the sound. Thornton was turning his horse to get a better look at the position, when he simply disintegrated before the eyes of his men. An impossible arcing shot from the distant battery had lofted a cannonball over an improbable distance to have it find Captain Seth Thornton, very much out of the blue. It was Seth’s war, after all, and near it’s end, the end of him.