Loss and grief have always made spiritualism marketable, but it also makes the séance more sordid than scary. It’s one thing for a carnival barker to rig the shell game against a kid trying for a gen-u-wine gold bracelet that will turn his girl’s wrist green. It’s quite another for predators to prey upon wounded people to separate them from their money.

For that reason, as long as there have been spiritualists, there have been hard-eyed realists who doubted and despised them. Which brings us to our subject for this Halloween. It is the 90th anniversary of Erik Wiesz’s death, a fellow who spent the last years of his life branding mediums as frauds and denouncing their antics as hoaxes.

You likely know him as Houdini, because under that name he was the most famous magician of all time. Reaching that pinnacle was no small feat for a Jewish kid from Budapest. By the time of his untimely death at age 52 in 1926, he had transformed his stage act into a series of spectacular illusions and physical feats that packed houses. Each season added more millions to the millions he seemed destined to make forever.

He was a small man at some 5’5”, compact and stocky with bowlegs, which made the sharp angles of his forehead, nose, and chin all the more arresting. Audiences all over the world were almost as fascinated by the “look” of Houdini as they were by his act, for he was exotic even in the alien lands of Russia with its slavs or Australia with its aborigines. His looks would have made Houdini forbidding except for his easy-going manner, bright blue eyes, and an inclination to laugh while cracking jokes. Comic relief leavened the dangerous stunts he performed and made them palatable, and despite a supreme confidence, he never condescended to the people in the seats. He did tricks, but he never tricked them. They always got more than their money’s worth.

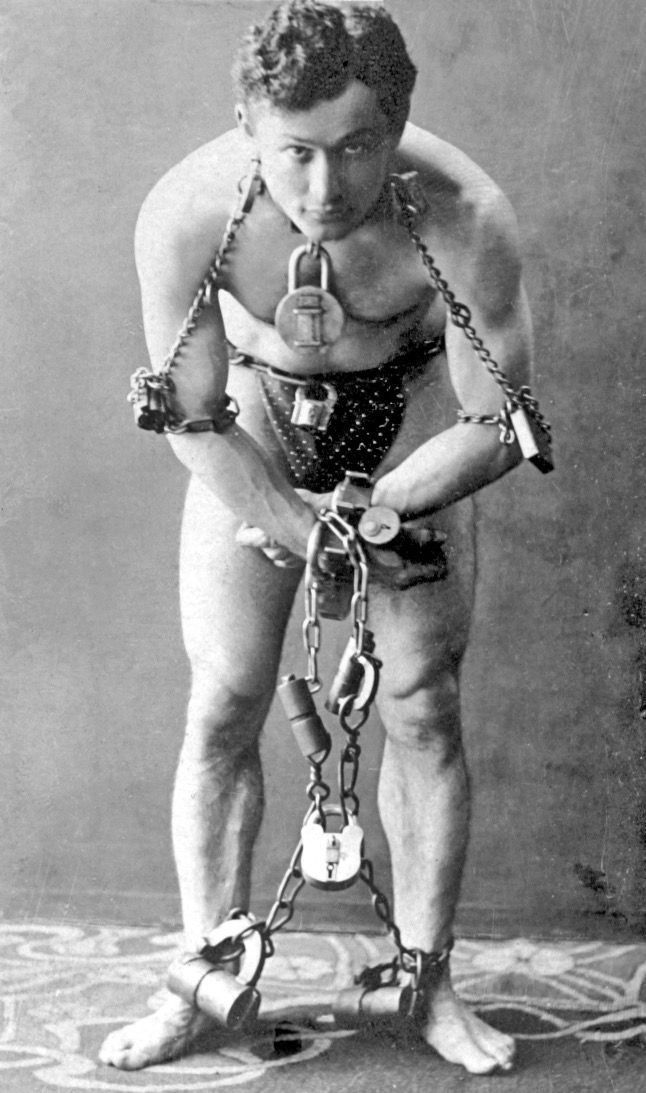

Houdini at 25

The physical part of Houdini’s repertoire was neither a trick nor an illusion, and it was what set him apart from his many imitators. His formative years were spent in America’s heartland because his father was a rabbi who moved his large family from Hungary to Appleton, Wisconsin, where he led its synagogue. Little Erik Weisz was 4, and the wholesome environment complemented his family’s moral center. It gave the boy a rock-ribbed sense of right and wrong, a belief that a reputation was something to be prized and protected. Any type of work was honorable if diligently attended by one’s best efforts. Not just Erik but his siblings learned this. In addition to grounding them, the environment made them athletic people. As Erik grew up, he changed from scrawny to muscular, just as he transformed his first name by Americanizing it to Harry.

The rabbi eventually moved his family to New York City, and Harry began winning medals in athletic competitions when he wasn’t doing a trapeze act with his brother for pennies from neighborhood kids. He also discovered a digital dexterity that he perfected with hours of practice. Manipulating cards in magical fashion with seeming ease was the result of natural physical talent blended with a Wisconsin work ethic. A brash but winning way was the Big Apple’s contribution.

Harry read everything he could about magicians. He idolized the French illusionist Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin, and from that passion came the final transformation of Erik Wiesz’s moniker into Harry Houdini. It was an homage, but at first it was also something of a joke because Houdini’s act was an unfocused mélange of physical stunts and card tricks. The crowds moving past his little booth on seedy midways were meager and soon moved on. He even tried spiritualism as he searched for something to set himself apart. He described his pretending to read minds and channel the dead as “a lark,” but after a time, he dropped the hokum. He saw grieving people wanting to believe it. It made the kid who had grown up in Wisconsin ashamed.

Meanwhile the boy who came of age in New York began to integrate his knowledge of mechanical things into his act. Houdini had always been curious about how things worked, particularly locks. He devoured technical manuals, spent hours at his tool bench, and practiced incessantly. He only took breaks to court a girl he and his brother had met while working at Coney Island. He married Beatrice Rahner, the girl he always called Bess and who became his on-stage assistant for the rest of his life. She was a good luck charm too. Houdini had a breakthrough with the locks, specifically handcuffs. His act became focused.

People who had passed on the card tricks now paused to watch the pretty girl handcuff the stocky, smiling lad. He turned away and slightly jerked his shoulders. He then wheeled with the cuffs off his wrists and in his hands. The crowds would gasp, and they grew. One evening a real agent with real connections saw the act and dropped by the booth afterward. He put Houdini on the Orpheum vaudeville circuit. The gasping crowds grew.

So did the act. On tour with Bess in spangles, Houdini could open locks with a pick so tiny it was undetectable. He stripped nude to allow grim-faced constables to examine his tongue, ears, and armpits and inform audiences that all was up-and-up. Houdini had secreted the pick in his anus. Nobody wanted to look there. He issued challenges to police departments to test him out with their constraints. He could pop almost all cuffs off his wrist in a fraction of a second, but he lengthened the time to best these challenge to increase the suspense. Word of mouth became a self-generating publicity for a man growing ever savvier in the art of self-promotion. He continued to practice and add to the act. More elaborate constraints such as chains with padlocks and airtight containers submerged in water made it exciting and dangerous.

Ropes were a different challenge. He flexed his large muscles when audience members tied him up and relaxed them to make slack for him to wiggle and wrench himself free. He studied every knot ever devised and knew the perfect amount of tension to make it seem taut and the perfect amount of loosening to make it slip. His bowlegs and his feet also came in handy, so to speak. He trained his toes to be as dextrous as his fingers and could both tie and untie complex cloves and hitches with this feet. He added a straitjacket escape to the act. When the novelty over that began to fade, he had authorities strap one on him and suspend him upside down over city streets. Thousands gathered on sidewalks to watch him wriggle free.

He began conquering Europe in 1900, and periodically launched tours there for the rest of his career. On the first one, he wowed Scotland Yard for publicity and then wowed packed houses in London’s famous Alhambra Theatre for an unprecedented run. The continent was soon at his feet, and the czar’s secret police were shaking his hand after he popped out of one of their inescapable security wagons, the ones they used to transport Russian political prisoners to Siberia. He returned to the United States an international celebrity with a bank balance sufficient to buy a grand brownstone in Harlem. A brass plaque still designates it as Harry Houdini’s house.

Meanwhile, he kept adding to the act. Houdini all but dropped the handcuff bit — everybody was imitating it — and devised increasingly dangerous escape stunts in which failure meant suffocation or drowning. The culmination of these was the Chinese Water Torture cell, an enormous glass box filled with water into which Houdini was submerged head first with his feet clasped by stocks. He privately called it the Up Side Down, or USD, and audiences were thrilled by it. They had reason to be. Houdini’s mental discipline matched his physical prowess. He could exert himself to extremity without increasing his heart rate. He invited audience members to hold their breath with him as he struggled to get free. Nobody ever lasted the better part of the almost five minutes it took for him to achieve his underwater escape.

He seemed flawless and superhuman, but that too was part of the act. Houdini was a good man, but he could be more than touchy about his reputation and his achievements. Some claimed he was obsessive about such matters. In Europe a Cologne detective claimed Houdini was being given keys to handcuffs. Houdini sued him and won. It became a litigious routine, and some of it was for publicity and therefore frivolous.

In addition to being sue-happy, Houdini nursed grudges. When the family of his idol Robert-Houdin treated him rudely, Houdini turned on them by publishing an acid critique of their patriarch as a charlatan who disgraced magicians by fleecing marks. And not everything Houdini touched turned to gold. He tried his hand making movies, but they flopped. He mounted a publishing effort, but it folded. And at the height of his success, he risked his reputation by attacking a popular movement whose advocates, when riled, could be as nasty and tenacious as he.

That is how Harry met Mina. She was Mina Stinson, a farmer’s daughter from Ontario who moved to Boston around the time of the First World War. Though still in her teens, she was adventurous and game for whatever life threw her way. It was said she sang with dance bands for a while, which is credible since in those days a “canary’s” looks were more important than her voice, and Mina was fetching. In fact, she was type of girl made famous after the war as the flamboyant “flapper.” Mina got married to a Boston green grocer, and they had a little boy, but Earl Rand couldn't hold Mina’s interest, and their life bored her to tears.

As it turned out, she was thoroughly modern Mina who did not long suffer. She did the unthinkable. She divorced Earl Rand in early 1918. There was another man prompting this bold move, and for Mina he was a better prospect in view of his social status and professional achievements.

She had met the accomplished surgeon Dr. Le Roi Goddard Crandon earlier, but he had not stolen her heart right away. Rather he had removed her appendix. By employing his nifty new surgical technique to reduce scarring, Dr. Crandon proved that the way to a girl’s heart was through her navel. Mina and Crandon met again about a year after her surgery when America’s entrance into the war had placed him on the staff of the New England Naval Hospital. Mina’s own navel installation had healed up sufficiently to allow her to get out of Earl’s house and drive an ambulance. Her eyes locked with Crandon’s one afternoon, and they were married shortly after her divorce.

At thirty, Mina Crandon became a jewel for her new husband. He was ten years older than she and had connections to Harvard, which meant an established social circle with an Ivy League cachet. Because of this it’s hard to say why Mina and her husband began acting like loons. Five years into their marriage, they began holding séances. Now by itself, that wasn’t crazy. In the 1920s, the Ouija “talking board” game was popular, and parlor entertainments featuring rapping noises and tilting tables were as common as charades. The difference for the Crandons, though, was what allegedly happened to Mina.

Without a prior trace of anything unusual about her, she suddenly became a psychic medium with extraordinary powers. She could move objects without touching them. She could talk to dead people. The favorite visitor from the other side was her brother Walter, who had perished in a 1911 train wreck. Walter spoke in a gruff voice and had a salty tongue. He made memorable the elegant little gatherings brought together by the Crandons’ invitation at their Beacon Hill home on Lime Street. Society matrons giggled over the expletives.

As word got out, others didn’t find it so funny. Harvard’s faculty wasn’t amused, but members of it were at least intrigued enough to investigate Mina’s powers. In 1923, several attended a few séances and came away convinced that Mrs. Crandon was a clever fraud. An associate editor of the prestigious journal Scientific American, however, attended one of these events and came away simply convinced. He suggested that Mina place herself in contention for a $2,500 prize the journal had put up for irrefutable proof that psychic events were legitimate. She and Dr. Crandon were more than willing.

And that is how Harry met Mina, though not at first. Scientific American had assembled a judging committee for this challenge. It’s most famous member was Harry Houdini. Including magicians on the committee was sensible — there was an amateur illusionist on the board along with Houdini — since their trained eyes could see through sleight-of-hand artifice, cleverly manipulated objects, and deceptive lighting effects. The committee had already debunked a couple of “mediums” by the time Mina Crandon came to its attention in 1924. The problem with Houdini was his touring schedule, and as it happened, he wouldn't even know that Mina Crandon was submitting herself to the committee until everything was nearly settled.

To protect her identity, Scientific American referred to her as “Margery,” and she soon became the most famous medium in the history of psychic phenomena. Her séances amazed the journal’s judges. “Walter” talked, and they listened. They dodged flying objects thrown by unseen hands. A table did more than tip; it toppled over. Lights winked, a bell secured in a box rang, luminescent wands hovered over luminescent checkerboards. They were on the verge of awarding Mina Crandon the prize when they thought to inform Harry Houdini, almost as an afterthought. He immediately cleared his calendar and descended on Boston like a man possessed.

In a way, he was. Houdini had once believed in spiritualism. When his mother died, he tried to communicate with her at séances, but he quickly discovered that every medium he consulted was a fraud. He discerned their most elaborate effects to be cheap tricks easily duplicated by even clumsy illusionists. In earlier times that sort of thing had made the boy raised in Wisconsin ashamed. While mourning for his mother, it made him angry.

He set aside part of his act to debunk spiritualists by showing how easily they deceived with their shabby effects. He published a book to reach a wider audience. And he discovered that some people who believed in this stuff refused to be persuaded and could never be convinced. His reputation for skepticism, though, made him a prized member of the Scientific American prize committee. And in July 1924, Harry Houdini at last saw two séances conducted by “Margery.” He immediately knew she was a fraud and was appalled that the committee was planning to recognize her as legitimate. He denounced everything about its “investigation” as irregular.

Members had stayed at the Lime Street residence. They had taken meals there. They became chummy with the subject of their inquiry. One had borrowed money from Dr. Crandon in sums he could never repay. One relationship with Mina was more than chummy. It was sexual. The editor who started the whole thing later claimed to have visited Mina’s bed as well, suggesting that her best tricks were not in séances but were the guys investigating them. In that respect, Houdini wasn’t surprised that Mina not only claimed to summon spirits but was a “free” one herself who sometimes conducted séances in the nude. It sounds more provocative than it was; séances were always held in darkness. But the committee’s collective imagination shed light on everything but Mina’s deception.

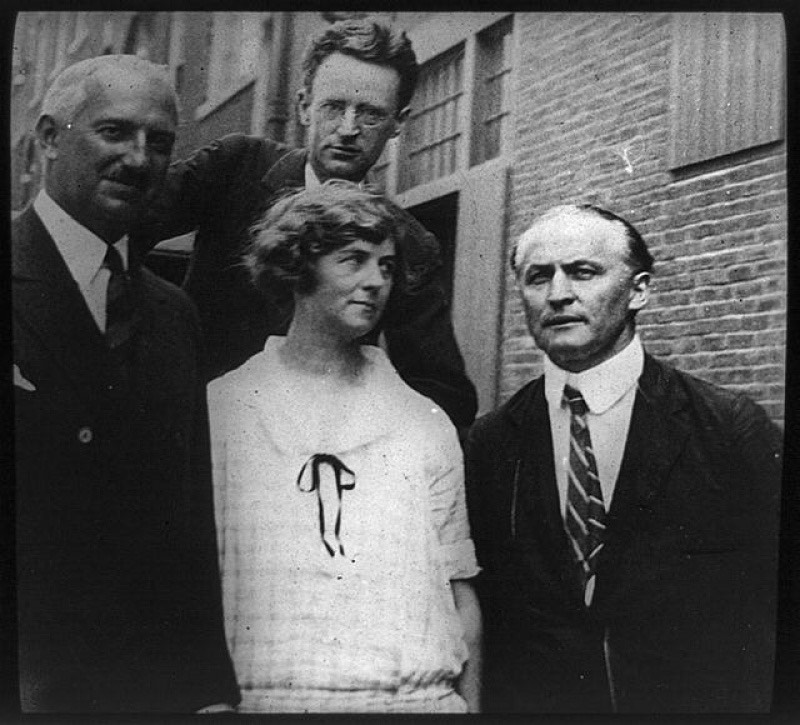

Houdini stands to Mina’s left. She knew he knew.

What mystified Harry Houdini, and still mystifies, was why Mina and her husband were going to all this trouble. They didn’t need the money, and they certainly should not have wanted the notoriety their activity was sure to bring. Yet, Houdini set aside the question of motive. His main concern was to quash the notoriety and expose the deception. He mounted a campaign so vehement that one of the committee’s more prestigious authorities exclaimed that Harry Houdini was the most obstinate man he had ever met.

All the same, because of Harry Houdini, Mina Crandon did not receive the prize.

The Crandon investigation was an episode in Houdini’s life rather than a milepost. Two years after it, he was still debunking cheap trick artists preying on grieving people. In October 1926, after a performance in Montreal, he was chatting with a couple of college students when one thought to test Houdini’s boast that his muscle tone could withstand any blow. Without warning, the young man struck Houdini four times in the abdomen, and the magician experienced an increasing pain for the few days left to him. Something — his appendix, colon, spleen, something — was broken inside him, and a raging fever forced him to bring down the curtain midway through his performance in Detroit a couple of days later. The doctors at Grace Hospital couldn't save him. He died about half past one on Halloween, 90 years ago.

Told the news, Mina Crandon gave a gracious statement to the press. She praised Harry Houdini’s tenacity. He might have smiled from “the other side.” Mina was tastefully dressed and said nice things about him, a fellow trickster, an enemy. Mina was behaving like a headliner, achieving for at least an instant what Harry Houdini had always been.

It took his dying, which was the greatest escape of all, but it also made for Houdini’s finest trick. Old vaudevillians bestowed it as the highest compliment. For a moment, he made Mina Crandon a Class Act.