In 1759, General John Forbes died today, March 11, after conducting the campaign that wrested the Ohio Country from the French during the Great War for Empire. That achievement was noteworthy, although it credits the British march on Fort Duquesne (situated at the site of what is now Pittsburgh) with more military prowess than it actually needed. What Forbes did that is often overlooked, however, had to do with a young Virginia militia colonel participating in the campaign. The lessons George Washington learned in 1755 from Edward Braddock about what not to do with an army were complemented three years later by John Forbes, who showed young Washington what was of uppermost importance when commanding one.

John Forbes

That would not have happened in the absence of Forbes. The British effort in North America in the first years of what British colonists called the French and Indian War had been haphazard at best. The defeat of Braddock’s column of regulars and militia in the summer of 1755 was a crushing setback. It made the French headquarters at distant Fort Duquesne seem unapproachable and thus secured their hold on the Ohio Country. For three years, London was convinced that nothing militarily good was likely to occur in that vast trackless wilderness.

It was not immediately apparent that changes were in the offing when England declared war on France in 1756. In fact, defeats and complicated alliances suggested the British had made a grievous mistake. But new political leaders gradually came to power in London and would change the empire’s fortunes by changing the direction of the global contest. The king's chief minister was William Pitt, who concluded that the war being waged in Europe and across the world in colonial outposts on the Asian subcontinent could actually be decided in North America. As a result, in 1758 three major campaigns took aim at French bastions in the New World. One targeted Nova Scotia, another Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain, and the third Fort Duquesne.

The British army in North America by 1758 was large and well supplied. For the Ohio campaign alone, Gen. John Forbes had more than 6,500 men, a force of regulars with militias from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. Many in these colonies had waited years for vengeance on the French and their Indian allies, none more than George Washington. Yet his obstinacy over the way to take the fight to the enemy almost ruined his part in it.

John Forbes was the most competent general officer Washington ever served under. He was not supremely gifted but was actually something of a plodder with all the qualities of one: prudence, reliability, frankness, and application, but above all prudence. A youthful fifty, he had developed a passion for logistics, the science of planning and organization. Carefully managing supply and communication seldom made hearts beat fast like derring-do charges led by sword-waving heroes in storybooks. But the more prosaic stuff of moving armies across unfamiliar ground always found favor with hungry, cold soldiers grateful to have rations show up and shoes regularly replaced. Forbes could get essentials to men on the march better than most, and he became a valued contributor to campaigns from the continent to Canada. Forbes had wanted to join the campaign led by Edward Braddock in 1755 as the army’s quartermaster general, but Braddock’s bad luck and Forbes’ good fortune tossed the job to someone else, and Forbes instead participated in British campaigns against the French in Canada where he won the confidence of his superiors. When the shadow cast by Braddock's disastrous defeat painted all projects in the Ohio wilderness as not just career killers but actual killers, British authorities were positive that Forbes was the man for the job. If anyone could drive the French out of the Ohio Country, it was sure, steady, reliable, prudent John Forbes.

In contrast to Edward Braddock’s lethargy, Forbes must have seemed effervescent. The Virginians were irritated that he set up his headquarters in Philadelphia rather than Alexandria, but the full importance of that problem was yet to come. At first, Forbes was reassuring because he seemed supremely skilled, involved, and attentive to every detail — up to the day he got sick. In mid-April he began feeling poorly, and in the weeks following diarrhea became dysentery to turn him into a virtual invalid. He had to supervise many preparations during the summer with long letters of instructions to subordinates who struggled to manage details.

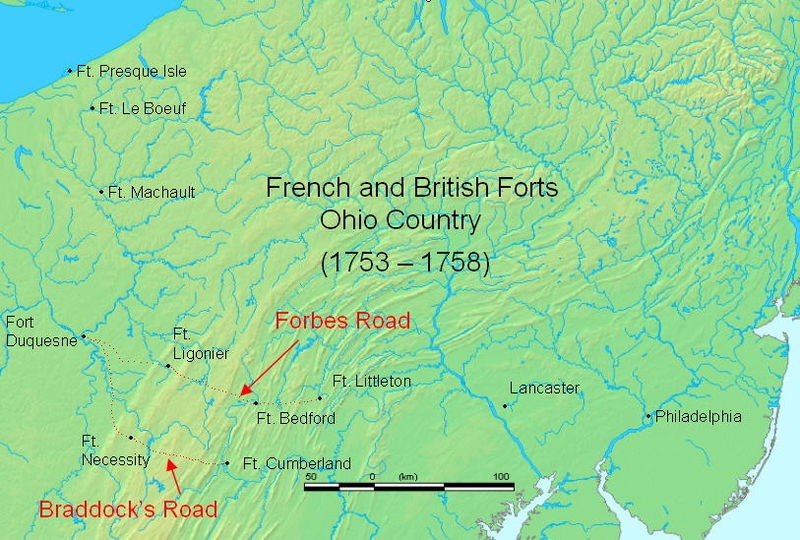

Virginians’ displeasure over the location of the British headquarters foreshadowed their significant discontent over another issue. Forbes had decided to approach Fort Duquesne on an entirely new road they would build through western Pennsylvania. Washington and other Virginians opposed the plan by insisting that Braddock’s Road from Fort Cumberland (on Wills Creek) provided many more advantages. Fueling some of these objections was Virginia’s jealousy over Pennsylvania’s receiving a new, direct avenue to the Forks of the Ohio, courtesy of the British army. Such a road would greatly favor Philadelphia as an entrepôt promoting settlement and economic growth. More to the immediate point, Washington had a strong case in that Braddock’s Road already existed, but his persistence and vehemence in pressing it as the summer wore on was too forceful and crossed the line of appropriate conduct and tone. Aside from flirting with insubordination, Washington broke one of his important rules of civility: “Strive not with your Superiors in argument, but always Submit your Judgment to others with Modesty.”

The Two “Roads” — one cut by Edward Braddock in 1755, and the other by Forbes in 1758 — were actually little more than trails in an otherwise trackless wilderness. Both were British avenues to the French at Fort Duquesne.

In September, Forbes ordered the Virginia regiments to join the main body of the army at Fort Bedford in Pennsylvania, the final signal that the new Pennsylvania road would be the one used, even though it was not yet finished. Forbes had finally lost patience, however, and sought to end the controversy with a direct order to Washington framed as a rebuke. As far as the general was concerned, the matter was closed.

Washington had little choice but to accept the situation, but he continued to grouse about the direction and management of the campaign. Meanwhile, British engineers encountered so many troubles with the new road that Washington’s objections to it seemed vindicated. Incessant rains frequently washed away daily progress as almost 1,500 men labored away on the long, hard job. It had delayed the army's start and was now slowing its progress. Washington fumed, but he did so quietly, and was able to mask his discontent effectively enough to win Forbes’s confidence. When Forbes reorganized the army, he placed Washington in command of a brigade, effectively making him a brigadier general in authority if not rank.

It was also becoming quite late in the season to start for the Forks of the Ohio. The unfinished road and bad weather were only two of the problems. Forbes claimed he was well enough to undertake the march, but he really wasn’t. He couldn’t sit a saddle and had to travel suspended in a sling between two horses. Apart from the inconvenience, his illness made him more cautious than usual, and after French and Indians badly mauled one of his forward scouting parties, he concluded that the enemy in their front was strong, numerous, and determined. The British march slowed to a creep, much to Washington’s disgust. Everyone became edgy. A fierce attack by the French at Loyal Hannon on October 12 was repulsed, but Washington had to ride between confused militia forces to stop them from firing on one another. The friendly fire incident was the only sustained action he saw in the campaign, and the deadly confusion of his supposedly capable militia deeply embarrassed him.

Forbes gauged the lateness of the season, took stock of the unfinished road, and made plans to put the army in winter quarters. Duquesne could wait until the spring. But just as rapidly as British fortunes in the Ohio Country had collapsed in 1755, France’s crumpled in 1758. Multiplying British offensives stretched the French too thin, and when Fort Duquesne was cut off, Indians began to abandon it. Told by prisoners of the deteriorating French situation at the Forks, Forbes quickly resumed his march. By the end of November, Fort Duquesne was his, a smoldering ruin the French had burned as they withdrew. Forbes renamed it Fort Pitt in honor of the first minister.

The capture of Fort Duquesne

It was a tame end to the violent war that Washington had caused five years earlier, but this last campaign was the most instructive for him. He had learned more about the rudiments of managing a large body of men in the few months with Forbes than all the years that preceded them. Caution was first and last the motto of that wary man, which was wisdom in the setting that had undone Edward Braddock. Protecting the army was the cardinal rule. Losing the army meant nothing else good could occur. Washington would absorb the lesson eventually, but at the time, he was extremely prejudiced against Forbes. John Forbes liked Washington and took the time through memoranda and instructions to conduct a tutorial in the art of logistics. The young man showed much promise if a fair amount of impudence, and Forbes maturely recognized that one could be cultivated and the other, up to a point, overlooked. As Washington let his anger over the road color his thinking and his frustrations with the British military establishment rise to the surface, he had not been able to appreciate the kindness and care shown him by this good man. The lesson of caution — of saving the army first and last, at all costs — was one Washington disdained at the time.

John Forbes never recovered from the stomach ailment that had laid him so low in the fall of 1758. When he died the following year on March 11, there was nothing to indicate that what he had done as a tutor to the youthful Virginia militia officer would have any other importance than to provide tales for telling around a hearth fire. Washington had already resigned his Virginia commission by the time Forbes died and was embarking on private life as a farmer. Sixteen years later, though, the Continental Congress would hand him command of an army, of sorts, and he would take it armed with the knowledge Forbes had imparted: Await opportunities, but save the army first and last, and at all costs; always, always, save the army, and at all costs.

With that as his rule, John Forbes’s reluctant student would win American independence.