In 1858, Abraham Lincoln suffered a crushing disappointment that seemed to make him a political failure beyond redemption. After reading the telegram that told him he had failed in his bid to unseat Senator Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln was despondently walking home in the dark when his right foot slipped on a patch of mud and nearly knocked his left leg out from under him. Limbs flailed the air as he managed some graceless contortions to avoid tumbling to the ground. As he caught his breath, he marveled that he felt better than he had all night. In fact, the incident made him oddly cheerful. “For such an awkward fellow, I was always pretty sure-footed,” he later said. It was like him to find symbolism in the commonplace. The depressing result in the Senate contest was like his stumble. “It’s a slip,” he thought, “not a fall.”

Lincoln’s resiliency as a war leader drew strength from that sentiment on countless occasions, for on the uncharted path of the enormous national emergency he confronted, he certainly made mistakes. But only hindsight reveals the errors. At the time, Lincoln’s decisions were always reasonable and carefully considered. The awkward fellow occasionally slipped, but the sure-footed one never fell.

For example, he is often faulted for a woeful ignorance of basic military concepts. It is because of this, it is said, that the first eighteen months of the Civil War are a chronicle of unrealistic expectations, impetuous directives for action, and disarray that resulted in incoherent assaults on the Confederacy's armies and resources. Yet the South's defiance of government authority was not unprecedented except in its scale. Lincoln could refer to George Washington's handling of moonshining farmers in western Pennsylvania during the Whiskey Rebellion, to Andrew Jackson's handling of South Carolina Nullifiers in 1833, to Rhode Island's handling of the Dorr insurgency in 1841, to the general government’s handling of defiant Mormons in the 1850s. In each of these instances, a show of force was enough to collapse rebellions and allow the government to show leniency with paroles and pardons.

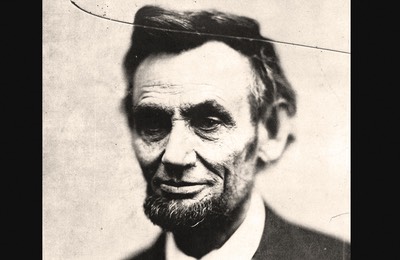

Lincoln’s last formal photograph at some time between February and April 1865 showed the rigors of the war in his face.

For the secession crisis already happening when Lincoln took office, he believed a rapid and sufficient show of resolve was imperative. The 75,000-man forced he called up for 90 days was equivalent in scale to Washington’s mobilizing militias against the Whiskey Boys, for who was to say that secession was not merely the Whiskey Rebellion writ large?

The outbreak of hostilities did not completely dissuade him from his course. For the first year, Lincoln adhered to a doctrine established by successful precedents of how to quell American rebellions, which was to overawe the insurgency. From that perspective, complicated plans to divide the South and deprive it of resources would take too long and possibly would not be necessary in the first place. Here was the thinking behind Lincoln’s desire in the summer of 1861 to have the Union army move before it was ready; here was the thinking behind his insistence that obvious pockets of unionism in places such as East Tennessee, northern Alabama, and the western counties of Virginia, be principal military objectives despite their limited strategic value.

We now know that Lincoln was wrong about the resolve of the southern rebellion, something he too discerned, marking a gradual shift to the “Hard War” policy that he was prepared to implement in the summer of 1862. By 1863, it was in full operation in all theaters. The resort to the hard hand of war indicates that Lincoln was desperately trying to reach what modern doctrine calls the tipping point in a military contest, that moment in a conflict when the enemy counts the costs of continued resistance as too high and admits defeat. It would appear that he did this intuitively rather than from a developing awareness of modern strategic doctrine.

What happened to the war under this new direction was sadly predictable: it simply spun out of control and proved illimitable in the damage wrought on the southern infrastructure and the hardships it worked on southern civilians. Lincoln watched helplessly as the war assumed its own terrible dynamic. His private utterances and public pronouncements reveal a growing fatalism about the general affairs of men and the specific ones he was trying to superintend. “I claim not to have controlled events,” he said, “but confess plainly that events have controlled me.”

Yet, the final months of incredible carnage and with victory assured by his reelection in 1864, Lincoln began to search for ways to reassert control, to dampen the hard war policy, to return to his assurances of the first inaugural address that the North and South were not natural enemies but fellow countrymen. He told Grant and Sherman to “let ‘em down easy,” and formally announced in his second inaugural address that the country would meet the coming challenges of peace “with malice toward none and charity for all.” These were stark statements of his determination to make reunion permanent and workable, to avoid acts of either grand or petty retribution and instead honor the dead for their sacrifices, comfort the living in their loss, and celebrate the new birth of freedom that unimaginable sacrifices had brought forth.

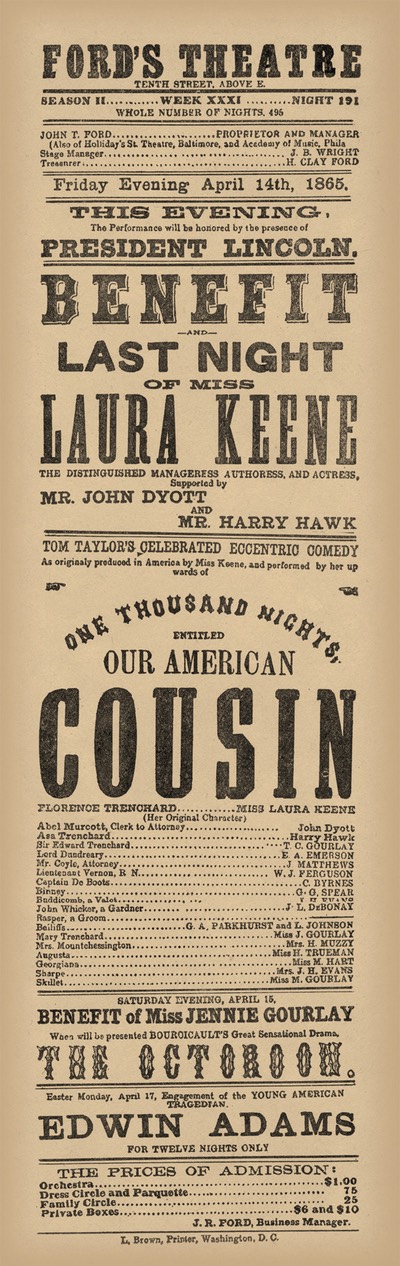

On April 14, the second act of British author Tom Taylor’s comedy was interrupted by a gunshot and then stopped by pandemonium after Lincoln’s assassin escaped across the stage.

We can only imagine how it might have turned out had murder not deprived us of the only man in the world who had a coherent, fully dimensional understanding of what the crisis and the war it had caused really meant. Lincoln's comprehensive vision was indispensable to a peace made palatable for the defeated. That vision could possibly have protected vulnerable former slaves and still have waged the turbulent and perilous political battles that were sure to follow the horrific military ones. Perhaps Lincoln would have failed in these crucial endeavors, but we shall never know. What is certain is that those who remained were more awkward and decidedly less sure-footed as they directed with imperfect planning and unsteady resolve the difficult process of reunion.

One afternoon late in the war, a friend of an Illinois friend called unannounced on Lincoln at the Executive Mansion. Secretary John Hay was dismayed because Lincoln relished such impromptu visits. Not only did Hay rightly predict that the president's appointments would be backed up for the rest of the day, but he was also anxious to pry Lincoln from the visit for the official chore of reviewing a regiment of Ohio volunteers. When the time came and Hay pointedly reminded Lincoln of the ceremony, Lincoln insisted that his guest accompany him to it. As the two men stood together and the soldiers began wheeling into place, Hay touched the visitor on the shoulder and told him to step back. Lincoln was clearly annoyed and cast Hay a fleeting frown before smiling at his guest to say, “That's so they'll know which one of us is president.”

The humility was both charming and misleading. Lincoln was sincerely humble as president, but only the densest of his contemporaries believed he didn’t know what he was doing in the job. Death could not mute his timeless words that speak to us as much as they spoke to the Americans of his time. In 1838, Lincoln was only 29 and his country was only 62 years from its Declaration of Independence. But he was troubled because his country was in trouble, beginning the long low growl over the strains of northern abolitionism and southern anger that threatened to become a full-throated snarl. Young Lincoln was confident that “all the armies of Europe, Asia, and Africa combined . . . with a Bonaparte for a commander, could not by force, take a drink from the Ohio, or make a track on the Blue Ridge.”

No, he said, the great national danger for America was from within; it was the monster that slumbered in the chaos of internal division. A quarter century later, when an older Lincoln saw that monster stirring, he provided the essential way to deal with an unparalleled national emergency: “The dogmas of the quiet past,” he said, “are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so must we think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.”

Which is what Abraham Lincoln did. Mortally wounded on the night of April 14, this good man died at 7:22 the following morning, awkward no more.

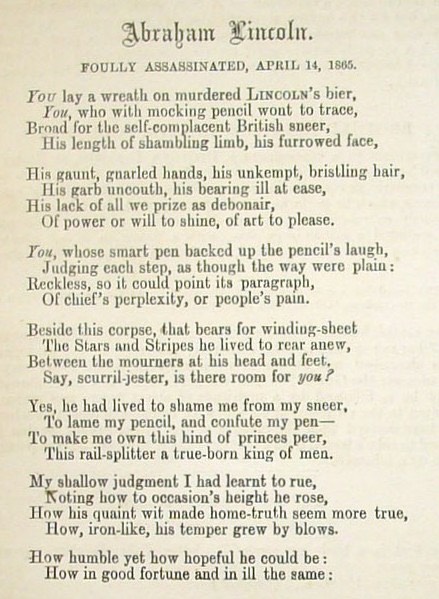

Tom Taylor, the same man who in 1858 had written Our American Cousin, wrote this mournful tribute for the British humor magazine Punch, which had often mocked Lincoln during the war. These are the poem’s opening stanzas from the May 6, 1865, issue.

_________________________________________