Thursday, April 9, of this week will mark the 150th anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s surrender to Ulysses G. Grant at Appomattox Court House. We had occasion to consider the event from a somewhat different perspective a few years back in our book on the Mexican War. What happened on April 9, 1865, was the end of a long odyssey of sorts for Grant and Lee, one that had begun years before and whose many turns leading to the little southern Virginia crossroads could not have been imagined by the most inventive novelist. The following is adapted from The Mexican War (2005).

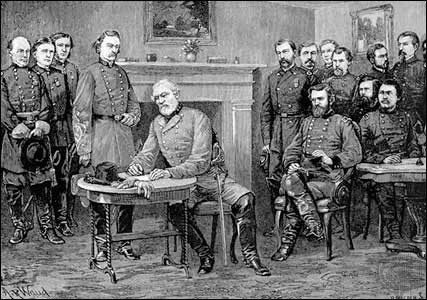

At the end of the Civil War on April 9, 1865, two generals sat down in the parlor of a modest dwelling in southern Virginia at a place called Appomattox Court House. One would dictate terms of surrender, and the other would be compelled by necessity to accept them.

“Sam” Grant got his nickname at West Point where his initials “U.S.” were said to have reminded classmate William T. Sherman of “Uncle Sam."

Robert E. Lee was a model cadet at West Point and an exemplary officer whose service to his country was not just unblemished but perfect. Then Virginia seceded from the Union.

Here was a strange reversal of fortune indeed, for the victor, Ulysses S. Grant, had been a lowly lieutenant during the Mexican War while the vanquished, Robert E. Lee, had been a lionized captain, one of Winfield Scott’s indispensable engineers. Before meeting him in Wilmer McLean’s house at Appomattox, Grant had seen Lee only one time, and it was in Mexico many years before. It was when Lee briefly visited the brigade to which Grant was attached, and Grant always remembered the event vividly. When the two met a second time—the momentous meeting in the small parlor that April day—Grant mentioned the first encounter, but Lee confessed he had no recollection of it, which was understandable. Grant was habitually unkempt and would not have made much of an impression. In fact, Grant was short, slight, and unconsciously furtive, which made him look as if he were trying to avoid a bill collector. Lee, on the other hand, had an effortless ability to appear pressed and polished under the most trying circumstances. He was also tall, muscular, and brimming with quiet confidence. Grant, like most people, always remembered meeting Robert E. Lee.

Grant’s service in Mexico had not been unmemorable (he was cited for bravery in combat), but it had not been particularly glamorous. Lee’s record was legendary. He discovered the path that made American victory possible at Cerro Gordo. Outside Mexico City, he crossed the impassable Pedregal to find a way through it with seeming ease. Winfield Scott spoke for many when he bluntly said, “God Almighty had to spit on his hands to make Bob Lee.”

After the Mexican War their lives could not have been more different. Sam Grant would leave the army, and his fortunes fell so low that he became nearly an indigent with a weakness for whiskey. Lee’s career remained steady and constant as he scored significant engineering achievements and rose to the rank of colonel. Scott wanted Lee to command the Union armies at the outset of the Civil War, but Lee would not bear arms against his native Virginia. Grant had been compelled to scramble for even a modest command, and his emergence as a talented general was gradual and marked by setbacks. Yet at the end on that April day the two men met again, and this time their pasts were completely irrelevant to their current circumstance. The impecunious and unprepossessing Grant at the head of the vast and burgeoning Army of the Potomac had won the war. The graceful and elegant Lee at the head of the ragged and dwindling Army of Northern Virginia had lost it.

For all their differences, though, their service in Mexico had struck them in a strangely similar way. In retrospect, both found that war troubling. Lee compared the American invasion to a bully browbeating a weakling, and Grant was later convinced that the entire episode was more than a direct cause of the Civil War. To Grant’s thinking, the horrors of the Civil War were retribution for Mexico. “Nations, like individuals,” he said, “are punished for their transgressions. We got our punishment in the most sanguinary and expensive war of modern times.”

At the surrender, Lee wordlessly corrected a minor grammatical error in Grant’s handwritten (and generous) terms

True enough, the conflict in Mexico carried few of the trappings of honor, and honor was supremely important to these two men throughout their lives. One desperately sought it, and the other wore it as a natural mantle. It must have seemed strange that the hard chores of soldiers, the marching and fighting and killing, had brought such bounty from Mexico at such little cost, until the actual bill finally came due. The Mexican War was not much of a war, as war was to be measured by Americans a decade and a half later. It cost the country about 13,000 dead, most of those from disease, and like all wars had been the setting for notable acts of heroism and villainy. But it was as nothing for the two generals, their fellow officers, and the survivors in their ranks, who could count a staggering 600,000 dead in the contest for the Union. That contest had been foreordained by the one years before in Mexico, the occasion when the scruffy lieutenant met the dazzling captain in the middle of nowhere, on a road that ultimately led to Appomattox.