Happy St. Patrick’s Day, everybody, and especially to friends of this website and our newsletter who hail from the auld sod. Raise a glass (or two, three!) in honor of the day. And while doing so, spend a few minutes here revisiting the circumstances that made March 17 another sort of big anniversary for the citizens of Boston. (For a story relating directly to St. Patrick’s Day, check out the special edition of our newsletter "An American Album" that went out this morning.)

By the spring of 1776, the British army had been a presence in Boston for as long as anyone could remember. Beginning in the late 1760s and early 1770s, the government in London had responded to New England protests by quartering a growing number of soldiers there, and they had become unpopular as events created higher tensions. In some cases, they contributed to the higher tensions, as when a mêlée in 1770 between Bostonians and a group of soldiers became known throughout the colonies as “the Boston massacre.” It all convinced the king’s ministers that the peskiest of Americans were those residing in the Bay Colony, and for a while, the king’s ministers had a point, as the Sons of Liberty’s reaction to imported tea seemed to prove. In April 1775, after the defiance of Massachusetts prompted the ill-fated march on Lexington and Concord to confiscate gunpowder stores, the British army in Boston ceased to be a quartered force and became an occupying one.

That situation came to an abrupt end on March 17, 1776, in large part because of the exploits of Henry Knox, who became one of George Washington’s most valued lieutenants. Knox did something remarkable that compelled the British occupiers to leave Boston, and we tell that story in Washington’s Circle: The Creation of the President, which went on sale today. The following excerpt has been adapted for this post.

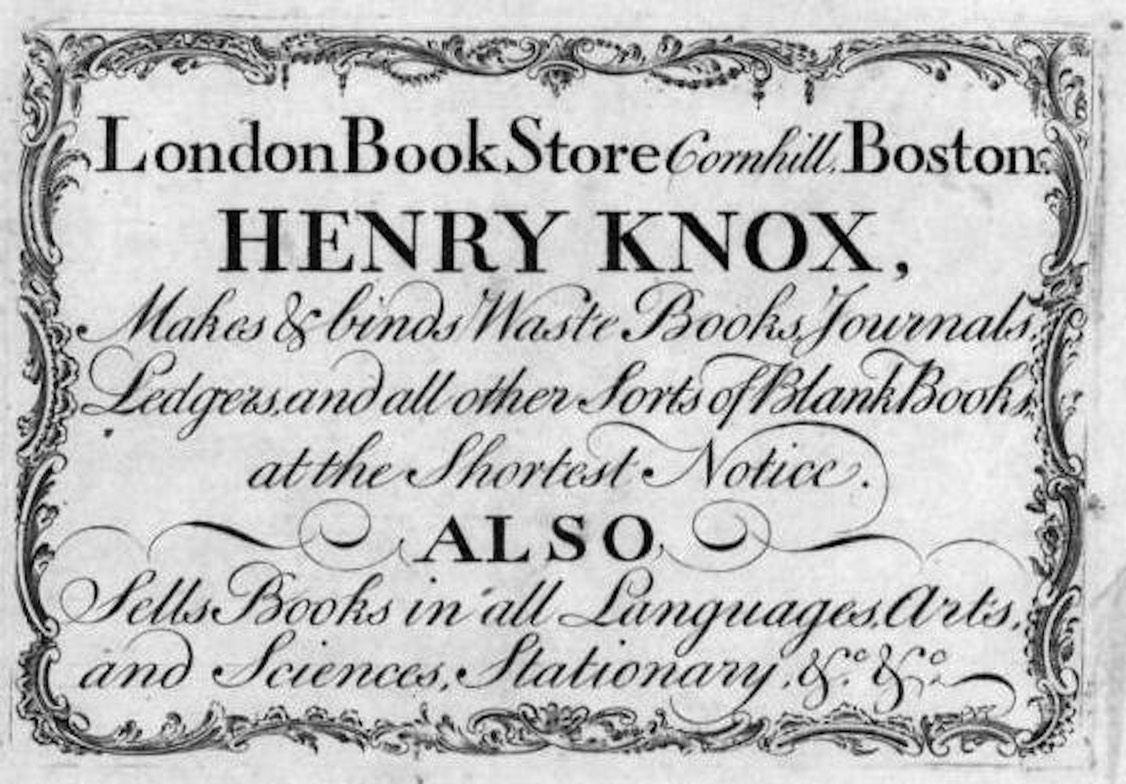

George Washington first met Henry Knox outside of Boston when taking command of the army in 1775, and the young man’s earnestness had impressed him from the start. Before the Revolution, Knox was a bookseller by trade if not by choice. His father’s untimely death had required him to leave school and apprentice in a bookshop when he was not more than a child. But Knox had immersed himself in the store’s stock, and his wide reading stoked a native intelligence. He became especially interested in military history, and specifically the use of artillery. It became a form of escape for him. His family’s straitened financial situation filled him with a lifelong dread of poverty. No matter how affluent Knox became, he would always be afraid he was on the verge of losing everything. At certain points in his life, it was almost a self-fulfilling prophecy.

By 1771, Henry Knox had an established store that was more than it seemed to be

Even so, Knox was not a cautious youth. His Boston was not Beacon Hill gentility but boisterous streets with roving gangs, places where a boy’s nimble wit and quicker fists were the weapons of choice, with the latter much preferred. He learned how to take care of himself and move easily in the company of rough men and rowdy boys. He also had a way of turning up at public disorders: he was a witness to the Boston Massacre and some accounts place him at the Boston Tea Party, but his level of participation is shadowy. With the limited prospects of a bookseller, it is little wonder that when he took an interest in the plump Flucker girl, her family looked askance at him. Worse, as the troubles with Britain intensified in Boston to make it the center of colonial agitation, Knox was not at all a reluctant revolutionary. That was the final straw for Lucy Flucker’s Loyalist family. They did not approve. She did not care.

Henry Knox became a newlywed on the eve of the Revolution. He was tall and sandy-haired with a way about him that charmed Lucy, who always called him “Harry” and was selflessly devoted to him for the rest of their lives. She did not mind that he was in the thick of things. There was an air of daring about her Harry, as when he blew two fingers off his left hand with a hunting rifle the year before their marriage. He nonchalantly tied up the mangled members with a handkerchief until he could visit a doctor to be sewed up. He and his friend the silversmith Paul Revere worked out a ruse to deceive the British who were vigilant for sedition. When soldiers loitered in Knox’s bookshop to eavesdrop, Revere would drop by to quarrel with him about loyalty to the Crown. Revere was always the loyal subject and Knox the disgruntled colonial. The British trusted Paul Revere, who was highly active in the Sons of Liberty, while distracting themselves over the bookseller, a decoy. By the time of Lexington and Concord, however, this type of playacting had put Knox among those at the top of an arrest list, and he was in danger the moment the British recovered from the shock of the skirmish. He and Lucy fled Boston in disguise. There was something about her Harry.

Knox’s knowledge of artillery was bolstered by his pre-war membership in artillery clubs that gave him practical experience. It came in handy at Breed’s Hill before Washington arrived, and by the time the grave Virginian pulled into Cambridge, Knox was highly valued by General Artemas Ward, the man who turned over the ragged army to Washington. The twenty-five-year old New Englander, as tall as Washington and able to look him in the eye, was welcoming, and in those first tense days, that was an endearing quality for the stranger from the South. “General Washington,” Knox told Lucy, “fills his place with vast ease and dignity.”

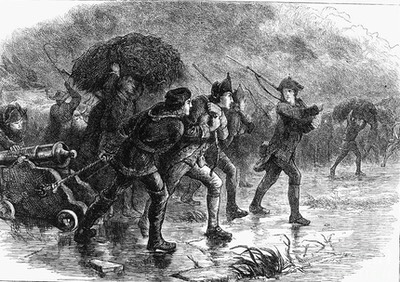

The Continental Army places Ticonderoga’s cannons on Dorchester Heights, courtesy of Henry Knox

The friendliness Washington felt toward Knox became soaring affection after the bookseller pulled off one of the most daring stunts of the war. He went to the captured Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain and brought its cannon to Boston. The simplicity of that sentence disguises the audacity of the deed. Nobody else in the world but George Washington and Henry Knox thought it possible to haul heavy artillery over three hundred miles of terrible terrain with ice-skimmed rivers adding awful variety to the trip.

Washington had his doubts, but he figured nothing would be lost in the trying. Yet Knox had developed a first-class case of hero worship that would have goaded him to drive artillery through the gates of hell for His Excellency General Washington. The route from Champlain to Boston was a near facsimile of the gates of hell, and news of Knox’s approach with his batteries was so delightfully shocking that it marked one of the two or three times during the eight years of war that Washington almost wept. Installed on Dorchester Heights overlooking the British positions, the cannon threw the British into a panicked evacuation that lifted the occupation of Boston on March 17, 1776. That alone boosted American morale and bought the Continental Army time.

George Washington would always remember the moment he galloped out on the road from Cambridge and found Henry Knox shouting orders, directing traffic, and beaming over those great big beautiful guns. Boston would never forget the deed or the day.