The French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon was born today, March 25, in 1741. Forty-four years later he was aboard a ship in the midst of a dreadful Atlantic crossing traveling to fulfill one of the most important commissions of his career. A stocky man with deft hands and powerful shoulders, he arrived in America in the autumn of 1785 to produce a full-length statue of George Washington. It was to be the centerpiece in the Virginia capitol’s rotunda, a building designed by Thomas Jefferson and under construction in Richmond. Benjamin Franklin in Paris had set the plan in motion, but it was Jefferson who chose the artist.

Houdon

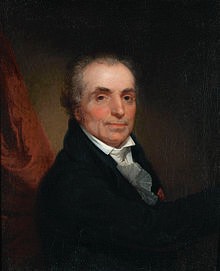

Houdon was the most celebrated sculptor in Europe. Born into a humble household, he nonetheless knew opulence because the humble household was at Versailles, and his father was in domestic service to highly placed people. When Houdon’s father landed a position as the concierge for a Parisian preparatory school, he was able to send his talented son to a sister institution in Rome to study art. At first, the boy gravitated to traditional subjects such as ancient mythology, and he was winning prizes as early as his twenties. Yet he soon began to produce the work that earned him accolades. Marble was his preferred medium, and like all great artists he resisted established forms and cultivated his own style. His statues did not just look like the persons they portrayed; they were the persons in the way they projected personality and character.

All Europe admired his magnificent busts of great men. His subjects ranged from the encyclopedist Denis Diderot to Benjamin Franklin, so his fee of 25,000 livres or roughly $5000 (more than $100,000 in modern value) was not unexpected, and the sum did not faze Jefferson. In fact, Houdon’s quest for perfection became clear immediately after Jefferson proposed that Houdon simply paint Washington’s portrait. Houdon said that a full statue would be a more commanding figure for the rotunda. Agreeing to that change, Jefferson expected Houdon to work in his Paris studio with a painting of Washington for his guide, but Houdon insisted that the result would be hopelessly inferior. He wanted to travel to Virginia and stay at Mount Vernon to observe Washington firsthand, make casts, take measurements, and complete the tasks essential not only for realism but for that intangible quality that made Houdon’s artistry matchless. After taking out $10,000 of life insurance on the artist, Jefferson booked passage for him and three assistants on the London Packet, which was the ship carrying Benjamin Franklin home.

Houdon and Franklin did not socialize on the voyage since Franklin kept busy writing scientific treatises and Houdon was constantly seasick. Wicked weather dogged the crossing from Le Havre to Britain, and the Atlantic pounded the ship as it strained toward America. Troubles multiplied when Houdon outpaced his luggage and had to borrow clothes. Most of all, however, he worried about how he could manage without his supplies and equipment.

His bad luck continued when he and his modest entourage finally arrived at Mount Vernon on a chilly October night two hours after Washington’s bedtime. The travelers had collared a French émigré in Alexandria, a merchant necessary for introductions because Houdon could speak only a few phrases of broken English. It made for a comical scene when Washington padded down to investigate the commotion. He likely saw nothing amusing about it, but he was characteristically hospitable.

The Life Mask

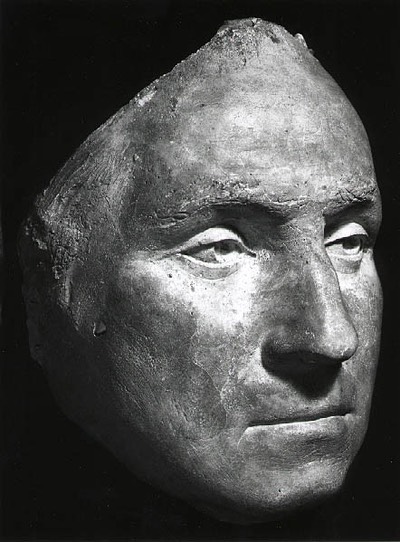

As he settled in at Mount Vernon, Houdon had a sinking sensation of impending failure. George Washington was cordial by nature but aloof from habit, and Houdon could not pierce the man’s reserve. When the weather turned drizzly, he coaxed Washington into sitting still for a few hours while he worked up a clay bust from life, using calipers for precise measurements of the general’s nose, brow, chin, and ears. He also wanted a life mask, an ordeal that Washington only grudgingly consented to because he was curious about how life masks were done. With goose quills protruding from his nostrils, Washington closed his eyes and kept his mouth tightly shut as Houdon slathered homemade plaster of Paris on him by hand and removed air pockets with a brush. It took less than ten minutes to begin hardening, and the chemical process made the plaster uncomfortably warm. Six-year-old Nelly Custis had to be reassured that her grandfather was not dead.

Houdon used the mold to make a replica of Washington’s face, and worked in the details as only he could. He left Mount Vernon in mid-October and by Christmas was home to begin work on the statue., It took him longer to finish than had been scheduled, but he was determined to get it right. He did not complete his work until 1792, but the delay did not matter. Slow construction on the Virginia capitol meant the state would not be prepared to receive the statue for another five years. So it wasn’t until 1796, when Washington was ending his presidency, that Houdon’s massive plinth, large marble column of fasces, and the towering likeness were finally crated. It amounted to eighteen tons of fine Carrera marble that was loaded on the ship Planter for transport.

Houdon did not receive the full sum of his commission for almost a decade after delivery, and by then George Washington had been dead four years, and the man who had hired Houdon, Thomas Jefferson, was president. Among the less urgent duties Thomas Jefferson assigned to James Monroe as envoy to France was to pay the sculptor, an incident of rather than the purpose of Monroe’s trip, which was to buy New Orleans, the transaction that gave the country Louisiana.

Houdon’s Washington became the dominant feature of the rotunda in Jefferson’s grandly conceived state capitol. Washington stands in uniform with his cape draped over fasces. He holds in his right hand a cane rather than a sword, which like the cape is set apart on the fasces. Behind him is a plow, the evocation of Cincinnatus as the warrior turned farmer. Washington is striking a resolute attitude that seems to look toward the future from a confident past.

"Houdon Makes It"

It was a magnificent achievement that had been helped along by a bit of luck while Houdon was still at Mount Vernon. One morning at breakfast, Washington was called away to meet a man about purchasing a couple of horses. Houdon had been following Washington for days, and he trailed along this time to watch the negotiations. He didn’t understand a word of what was being said, but watching Washington haggle was fascinating, and as the two bargainers got down to cases, the visitor named his price. Washington thought it too high. He tilted his head back and snorted his disapproval. Houdon scored the image into his memory. At that instant, Washington’s face was the window on the man, something all the charcoal studies and plaster casts in the world would never provide. It had taken days, but the Frenchman had at last been introduced to his host.

It was the expression he used for his images of George Washington. It appears on the bust he baked into terra-cotta and left at Mount Vernon as a gift, and it is the expression on the ones he reproduced in a sequence of molds for copies to aid his work in Paris. Washington’s family thought this bust was precisely him from the inside as well as the outer appearance. On the pedestal of the Washington statue in Richmond is this inscription: “Behold, Reader, the form of George Washington. For his worth, ask History; that will tell it, when this stone shall have yielded to the decays of time. His country erects this monument: Houdon makes it.”

He believed that with enough time and the right tools, he could show a man’s soul. As the simple, powerful inscription declares on the pedestal in the capitol rotunda, Houdon did make it and most finely indeed. But not until he had at last, after the space of several frustrating days at Mount Vernon, seen the soul inside the distant man. By pure chance, Houdon had glimpsed more than even a man haggling over a horse. He had seen an American. That is what he carved in the marble.