John Caldwell Calhoun died 165 years ago on March 31 in the midst of the worst political crisis the United States suffered before the one that caused the Civil War. By the time of his death, Calhoun had landed on the wrong side of the struggle, and history would not be kind. It hadn’t always been that way. He had started out as a committed nationalist almost 40 years earlier, and no man could have been more resolutely devoted to the Union after the War of 1812. Yet troubling events and personal disappointments gradually transformed him into a southern nationalist dedicated not only to the preservation of slavery but its expansion. One cannot get much farther on the wrong side of history than that.

Calhoun was a remarkable mixture of talent, industry, and guile. Tireless, diligent, and innovative in anything he undertook, he was almost able to surmount the deficits of character, place, and position with such unremitting competence that rivals often wondered what he was up to. Some deduced that Calhoun was quietly ruthless and ready to bowl over anyone who stood in his way. The truth of the matter was more complicated than that. Calhoun was born into a family of the South Carolina Scots-Irish community that had escaped the grinding labor of subsistence agriculture through hard work and natural aptitude. His family made sacrifices to put him in good schools, including Yale, where Calhoun established himself as something of a prodigy.

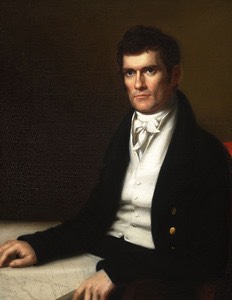

He married money. Floride Colhoun, John’s first cousin, was eleven years his junior, from the well-to-do side of the family, and fetching in her own right if a bit high-strung. Her name was pronounced like the state (Florida) rather than the dental treatment, and she was heiress to a fortune that allowed John to pursue politics and indulge an opulent lifestyle. Their courtship was ardent, although the one love poem that John penned for her oddly began every stanza with a lawyerly “Whereas,” a portent of his behavior after their marriage, which was always kind but never again passionate. Men nonetheless envied Calhoun for his beautiful, rich wife and his seemingly charmed political career, and they admired him for his talent as well as his dark, rugged good looks. Yet, almost nobody liked him.

It is hard to say why. Depending on who was doing the recollecting, Calhoun could be charming or cold, solicitous or dismissive, open to disagreement or pedantic to the point of obtuseness. Nobody resented his stately house called Oakly (later known as Dumbarton Oaks), which Floride’s mother had purchased for the couple. And everybody admired his graceful wife, and not just because she smelled of verbena and money. It was not even Calhoun’s arresting stare that signaled a first-class mind barely willing to suffer ordinary intellects, let alone fools. It was the impression that Calhoun was both enormously principled and thoroughly insincere, a humorless man who only chuckled when cued by the laughter of those who got the joke.

An example: In the fall of 1821, Calhoun promised to support a man for the presidency but privately mocked him and compared his possible election to a national calamity. By the following spring Calhoun was openly hostile toward this man. Ambition did not so much change John Calhoun as it revealed him. Shy by nature, he drove himself to become successful. His candidacy during the 1824 presidential contest became for him a great religious crusade, a messianic mission to save the country from certain destruction, and he never again abandoned the motif in anything he did. It was as good an excuse as any for public rectitude and private treachery. Those who saw only the rectitude supported him; those who felt the treachery distrusted him. Almost nobody liked him. In a way it was emblematic of Calhoun that he was vice president for both John Quincy Adams and Adams’s mortal enemy Andrew Jackson, making Calhoun unique in the annals of that office for serving two consecutive terms in it under diametrically opposed administrations.

Calhoun’s passions were so relentlessly suppressed under his didactic manner that they became both forge and anvil on the rugged good looks of his youth. It made everything about him seem stark, severe, and metallic. His eyes were often fixed in an angry stare, as the Matthew Brady daguerreotype famously depicts, but by the time he was sitting in front of Brady’s camera, Calhoun was angry about almost everything. His ambition to become president never stood a better chance than in 1824 when he was an early casualty of Andrew Jackson’s popularity, but he continued to hold out forlorn hope. His efforts to promote an obstructionist philosophy grounded in states’ rights did horrific damage to the very concept he meant to defend by lashing it to primitive and disgraceful rationalizations for chattel slavery. His attempt to have this philosophy given practical application with nullification in South Carolina nearly caused the Civil War in 1833 while almost irrevocably wrecking his reputation among suspicious northerners and prudent southerners. The British traveler Harriet Martineau met him shortly after this and described him as “the cast-iron man who looks as if he had never been born, and never could be extinguished.”

The Toll of Anger

His political maneuverings after a time carried the taint of opportunism, and his friendships seemed only temporary alliances. Some of those perceptions were unfair, but Calhoun was helpless to correct them. It was undeniable, though, that he was supremely gifted with a machine like intelligence that could catch the unwary unawares and cause both allies and enemies to look down, think, and then stare back in silence. His talents matched him with the other giants of his time, Daniel Webster and Henry Clay. The three were called the “Great Triumvirate” to mark an era in the U.S. Senate when titans clashed, cooperated, and could speak for hours without notes and without hesitation to captivated colleagues and hushed visitors packing the Senate gallery.

That happened for the last time in the terrible crisis we mentioned in the opening. At least, it happened in a way. It was the same insoluble problem that had been plaguing the country since its founding, the controversy over slavery in half of it and a growing disposition by the other half to stop its spread. Henry Clay was frantically seeking a solution through compromise and spoke eloquently for his cause. Daniel Webster made one of his timber-shivering orations on behalf of the Union. But in that fateful spring of 1850, Calhoun was already too frail with tuberculosis to deliver his swan song. He had to sit quietly brooding while a fellow southerner read it aloud for him to a somber chamber where all realized they were hearing a grim valedictory. By saying that the South could accept no more compromise, Calhoun gave all the appearance of having forsaken the Union.

By then, everyone knew John C. Calhoun was dying. He knew it too. He was confined to his rooms, weak but still alert. Henry Clay wanted to see him. They had begun together in Congress so many years before, boarding in what was called the War Mess when the new country was on the verge of challenging Britain over honor as much as commerce. They had done that, had stared without blinking at the most powerful empire on earth, the talented boy from the Carolina Upcountry and the magnetic one from the Virginia Slashes, a good team. Then they had been immortal. Now they were old men, sick like the country, and divided over slavery and sectionalism, like the country. Hardly any but hard words had passed between them for a quarter century, but Calhoun said to come on. Clay appeared for the appointment smiling and solicitous, but Calhoun could not put away his anger, even for an hour. Calhoun’s fellow South Carolinian Andrew Pickens Butler stood at the edge of the room and watched the two men simply sitting in silence. Clay had a kind smile and Calhoun a distant stare. Butler thought of giants in the twilight.